Seventy-five years of education: Part - II

The first half of the 1970s brought both good and bad news for education in Pakistan. The good news was that the Bhutto government had a plan to offer free education to all under the nationalization programme rather than relying on the private sector.

The idea was to improve and strengthen the government sector in education so that a more egalitarian approach towards learning and teaching prevailed in the country. Bhutto claimed to be a socialist and in that outlook the private sector had little role to play. By the 1970s, there were some big and good educational institutions that prominent philanthropists and foundations had established. They were not large in number, and catered to the needs of their limited catchment areas. Bhutto considered that private education promoted class differences and the government had the right to run them under its umbrella.

So initially it was good news for common people who thought their children would receive the same quality of education that some private institutions offered. The PPP government in Sindh also took a correct and timely step to introduce Sindhi language as a compulsory subject right from school education. One wonders why the PPP government in Punjab did not do the same by introducing Punjabi language as a compulsory subject.

However, there was an instantaneous reaction against the introduction of Sindhi. There were student protests and riots in and out of educational institutions; ethnic tensions mounted and Bhutto negotiated with the leaders of those opposing the language compulsion.

Bhutto also launched a massive plan of establishing new government colleges and universities across the country. Higher education was now relatively more accessible and those who could get admission completed their education almost free. Even engineering and medical colleges and universities charged next to nothing; engineers and doctors graduated at public expense. Faculty members had job security with pensionable employment and promotion opportunities.

Within five years, the dream had gone sour. We need to understand education in its broader perspective. It is not simply the quantity of educational institutions that matters – what you teach and how you teach it makes the difference. Bhutto had a golden opportunity to revamp the curriculum that could change the course of education in the country with more analytical skills and critical thinking. More than education in science, it is the social sciences that alter the cultural, economic, political, and social outlook of students.

Education in civics, ethics, geography, history, and other social sciences can make or break a young generation. Bhutto could give a new direction to social science education by having a critical look at the first 25 years of Pakistan. Most of all, the recent events in East Pakistan that had resulted in massive atrocities and killing of hundreds of thousands of people needed a fair analysis and discussion. Germany and Italy after the Second World War made sure that their children and young generation knew about atrocities that their own people had committed.

Rather than accepting one’s past errors and missteps, Bhutto kept promoting an obsolete narrative of national grandeur and hero worship. Bhutto’s policies of ‘fighting for a thousand years’ and ‘eating grass to make the atomic bomb’ reflected in education too. History books overall remained the same with no room for critical analysis of the past and no discussion on multiple perspectives. Bhutto lost that opportunity and strengthened the old and one-sided state narrative that bordered on chauvinism and contained jingoistic elements. Bhutto’s policies towards minorities were also anachronistic and his constitutional amendments set the course for more persecution.

His nationalization of education could have produced better results but it had some major flaws. Recruitment in the schools and colleges should have been on merit but that didn’t happen. The hiring process was skewed in favour of political appointments, of course with some joining on merit. Education became one of the largest employment providers by the government, with a majority of new teachers without the knowledge and skills that their profession demanded. Like other sectors that had gone through the nationalization process, the education sector also became a behemoth with hundreds of thousands of incompetent administrators and educators who were mostly unskilled.

This does not mean that during the military dictatorships of Generals Ayub and Yahya education was any better. Perhaps it was worse, but at least there were some educational institutions under private management that were offering slightly better education. Bhutto’s assumption that all private educational institutions were exploitative and needed government control was also incorrect. There were many foundations and trusts that did not run on profit motives. The government should have allowed them to continue working independently without direct government control. State control badly affected their performance and most of them declined sharply.

Another adverse impact of Bhutto’s policies was an abrupt end to any new investment in education by non-government sources that included both for-profit and nonprofit. From 1972 onwards for at least a decade only the government of Pakistan could open and run educational institutions. This imposed restriction was uncalled for and unwise. From 1870 to 1970, the country had seen the establishment of some fine institutions such as FC College, NED University, DJ Science College, Dawood Engineering College, St Joseph’s and St Patrick’s Colleges, and many other schools, colleges, and universities.

Now suddenly the government was in charge of all education and no private investment came up. This had far-reaching implications for education in Pakistan. The Bhutto government did try to fill the gap but the broader policy of giving precedence to security did not leave much in financial resources to spend on education. Bhutto’s obsession with the security establishment in the hope of deriving strength from there, was misplaced and the stronger he made that establishment the weaker he emerged on other fronts. This was a major cause of his undoing and the failure of his most policies.

But at least student associations and unions were functioning well during the entire tenure of the Bhutto government. There were heated debates on campuses, both conservative and progressive outfits had candidates contesting elections for student unions. Apart from sporadic crackdowns on protesting students, there was a thriving culture of political awareness that trained students for civic and political responsibilities. Anjuman Talaba-e-Islam, Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba, National Student Federation, People’s Student Federation, and numerous other conservative, liberal, nationalist, and progressive students’ association held conferences and conventions on and off campus. There was always a threat of government crackdown but overall it was not as suffocating as it became later on.

The last months of the Bhutto government in 1977 were perhaps a turning point for education as the conservative onslaught on Bhutto intensified. The Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) made its inroads into educational institutions too, with a highly toxic agenda of eliminating all liberal and progressive thought from campuses and from society. All student associations with a religious orientation allied with the PNA against Bhutto and when he won the elections with some election irregularities the campuses also became a battleground. I was in eighth class and was happy that schools were closed for months due to the PNA agitation.

In April 1977, the government announced that students would be promoted to their next class without any exams. We were delighted, not having a clue that the next few months would see the beginning of an even darker era for education in Pakistan under General Ziaul Haq.

Concluded.

The writer holds a PhD from the University of Birmingham, UK.

Email: mnazir1964@yahoo.co.uk

Twitter: @NaazirMahmood

-

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

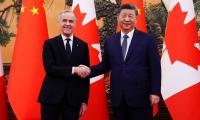

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training -

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light -

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push -

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down -

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career -

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer -

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis -

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI -

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds -

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years -

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome