Nasty, brutish and short

Nasty, brutish and short. That is how Thomas Hobbes described life in the state of nature, a setting in which there were no enforceable criteria of right and wrong. People took for themselves all that they could, and thus human life was “poor, nasty, brutish and short”.

The solution for Hobbes was an all-empowered sovereign – the state or a monarch – to enforce order as it wished under a “social contract” with the governed. Much of political philosophy ever since has been devoted to understanding and expanding the nature of this social contract and thus the rights of the state and the citizenry.

Pakistan, alas, has never had a functioning social contract, the Captain’s vague vision of a Medina-ki-Riyasat notwithstanding.

We exist more in a state of purgatory, on the fringes of Hobbes's state of nature. Our rights are fragile and our existence tenuous. Our state is one which is perfectly capable of exercising violence, but does so mostly arbitrarily and capriciously. Aurat March participants, beat ‘em up. Pashtun nationalists, lock ‘em up. APS terrorists, engage for amnesty. And Faizabad protesters, dole out the dinars.

This capriciousness of state violence is what makes us different from other, more ‘well-adjusted’, states. It also helps shape who we are as a people, as a culture and as a society.

Why, after all, do so many amongst us ostensibly welcome the Taliban takeover of our hapless neighbour. Surely not because we approve of their values – ask the man on the street and most would say that they personally don’t wish to live like that (or so one wishes to imagine) – but there is yet a certain fascination with the Taliban’s perceived use of violence. It is absolute, it is brutal and it is seemingly indiscriminate. For the average person, there is predictability in such uniformity – and predictable violence is preferable to irrational violence.

We endure what I label the ‘Grace of God’ syndrome. We observe such a surfeit of unfairness and injustice everywhere – the property mafia, medical malpractice, police brutality – that the average person exists in a state of perpetual stress: “there but for the grace of God go I” The state offers little protection and might seems to make right.

The life of the lone individual is destined to be nasty, brutish and short. And with a state that is perennially incapable of providing reliable refuge – after all, it’s the very entity that ceded its own territory, and the citizens within it, to the Swat Taliban in 2009 – what is a survival-minded person to do?

Turns out that the instrument for God’s grace lies, in part, in tribal instincts. Not merely along obvious ethnic or linguistic lines, but tribes of lawyers, of doctors, of civil servants, of extended families and even entire mohallas. The tribe is the basic unit of protection, the shield that will rise to individual defence.

The grundnorm of such a compact is that the tribe does not judge, it only defends. When a lawyer faces suspension for beating up a judge (yes, this too has come to pass here), the bar associations rarely question whether the lawyer was right or wrong. They strike (and if necessary, riot) in defence of their member. One for all and all for one.

Afterall, with fires of injustice raging everywhere, do we want our firefighters to first decide whether ours is a righteous blaze? Or do we expect them to rush unquestioning towards the flames?

In seeking protection without question, however, we must ourselves be ready to defend others without judgment. Hence the sorry spectacle of good people tolerating bad acts of their ‘tribal’ peers. We bear and even condone injustice (and the unjust) within our spheres because to call them out – to shun them – would be to break the tribal compact: thou shall not judge, thou shall only defend.

Taken to its extreme, it spawns a culture of ‘who you know’ and ‘what you belong to’. People end up with thousand person weddings not because they deeply adore every last acquaintance, but because societal networks need sustenance. In turn, attendees hit and run multiple weddings in an evening, often without knowing the names of the brides and grooms, because of the need to register their presence. It’s a tribal obligation, not a personal outing

This is, admittedly, a somewhat cynical take on our culture. No doubt people genuinely believe in and enjoy their expansive interconnectedness and celebrate it as part of our culture. Human actions are underpinned by complex and contradictory reasons – love, fear, admiration, belonging, need, want. But the need to be part of tribes – as many as possible – is the marginal motivation for many societal interactions.

In a sense, we have made virtue of necessity. Our culture is communitarian – we live, breathe and die amongst multitudes. The intimate 50 person weddings and funerals of the West are taken as evidence of individual isolation and societal decay – no matter that in those settings all present are deeply connected to the person and event; every presence is meaningful, each eulogy is personal.

There isn’t a single answer to societal organising principles, or whole areas of political philosophy would be redundant. But a sweet spot surely lies somewhere between the individualism of the West and the tribalism in our midst. A place where connections are expansive, but they are also meaningful. Where you attend funerals largely out of a sense of loss and solidarity. Where you judge a misbehaving fellow young doctor worthy of suspension, rather than stoically standing at the hospital barricades with the tribe. Where you can shun those whom you don’t like without worry that you might need them when your own ‘grace of God’ moment arrives.

These would be signs of a reorganised society that is strong and confident, where individuals are empowered rather than cowered. Where a young lawyer isn’t incredulous that I have no intent to vote for her bar election candidate even though – as she kept repeating – jatts always vote for jatts, it’s the way it is!

To have any chance of getting there, though, we need to heed Hobbes and focus on a social contract – any social contract – that is consistent, predictable and enforceable. Deliver basic property rights, protect simple freedoms, provide minimal security. A simple bill of rights, efficiently delivered.

Our state and constitution promise lofty rights and fall maddeningly short on virtually every count. Perhaps it's time now to think small, but deliver in full – forget the lofty pursuit of happiness, just deliver a life that isn’t nasty, brutish and short.

The writer, a former aide to UN Secretaries-General Kofi Annan and Ban Ki-moon, tweets @aliahsan001

-

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss -

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning -

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding -

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border -

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene -

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce -

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All'

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All' -

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals -

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked -

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

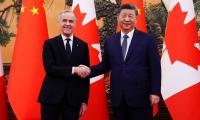

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training