A scholar of peace (Part - I)

When, as a young man looking for guidance, Wahiduddin moved from one source of knowledge to another, he realised that the books of the time were not sufficient. So he embarked on a journey of writing, which lasted three-quarters of a century.

By the time he died on April 21, 2021, at the age of 96 he had penned over 200 books and hundreds of articles and essays. Of course, for that much he had to read a lot, and through the course of his vast readings he managed to gather encyclopedic knowledge in diverse fields, especially in the fields of Islamic culture and history. His death sparked a renewed interest in him and his writings in Pakistan too. Scholar and writer Khaled Ahmed posted a good commentary on Maulana Wahiduddin’s book ‘Muslim Women and Modernity’ which is the English translation of his Urdu book.

Yasir Pirzada – whom I consider one of the best columnists in Urdu – wrote a brilliant column in daily Jang about Maulana Wahiduddin. Saleem Safi aired his interview with the Maulana taken in 2016 in Delhi.

My intellectual friend Aziz Ali Dad from Gilgit composed a fine write up in Urdu about Wahiduddin and enlightened us about the various aspects of his personality. Another writer of liberal and secular orientation, Arshad Mahmood, wondered why some progressive people are mourning a maulana who had no wisdom at all. He also posted a video clip in which Wahiduddin is stressing upon a good life in future and suggesting that those who are disappointed in the present must realise that the future will be better. Maulana Wahiduddin had a fair share of friends and enemies both in the religious right and the secular left.

Essentially, Maulana Wahiduddin was a religious scholar and writer. If you apply a strictly scientific and secular epistemology to define the contours of his knowledge, you will find his knowledge and understanding lacking in cogency and coherence. There are contradictions spread all over his writings. If you want to make a selection of his writings, you may end up collecting pieces that are diametrically opposed to each other. If you watch his videos, he appears to be impressive and insightful in some, and lacking in comprehension and intelligence in some others.

A lot has been written about his more famous books such as ‘Raz-e-Hayat’ (The secret of life), ‘Tabeer ki Ghalati’ (Error in interpretation) – in which he criticized Maulana Maudoodi, triggering a backlash from the Jamaat-Islami – ‘Asbaq-e-Tareekh’ (Lessons from History), etc. Here I would like to draw readers’ attention to some recurring themes in his writings. One of his concerns was the role of Ulema in the contemporary world. He dilated on this in several of his works. Take for example his essay titled ‘Ulema aur Daur-e-jadeed’ (Scholars and the modern age).

He presented this paper in 1992 at a seminar in Lucknow and reverted to this topic throughout his long academic career. In his discourse, he critically analyzes the leadership role of scholars in the new era. His main premise was that we should try to understand the intentions of Ulema separately as opposed to their actions or strategies they adopt to tackle the challenges of the modern world. The literal meaning of Ulema is knowledgeable people or scholars but in Urdu it has assumed the meaning of religious scholars only.

Wahiduddin outlines his case by criticizing Ulema’s strategies which failed to match the requirements of the modern world, resulting in a complete waste of their efforts and energies. He suggests a fundamental revision of the approach that Ulema have been taking over the centuries. According to Wahiduddin, a majority of the Ulema now lack understanding of the modern world and the upshot is an absence of vision in them to lead Muslims to a better future. He distinguishes between Jihad bil saif (crusade with sword) and Jihad bil ilm (crusade with knowledge).

To him, scholars cannot and should not try to lead both as these are two distinct fields of action. Those who get involved in political matters neglect their primary responsibilities of gathering and spreading knowledge among the masses. He suggests that Ulema should entirely devote their lives to education and training to make themselves and others better human beings. Maulana Wahiduddin was strictly against taking up arms or promoting violence in the name of religion. He thought that a real holy war is against ignorance and illiteracy.

He strongly believed and promoted the idea that politics and religion should not be mixed, and they should have different sets of leaders excelling in their own fields. So far, so good. But then the good Maulana ventures into an area in which his own biases against women become prominent.

Just like Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Wahiduddin was full of such contradictions. He considered men and women as having distinct and separate roles to play in society. Had he confined himself to biological roles, he would have made better sense in today’s world – the world that he thinks the other Ulema do not understand properly. But in society itself, Wahiduddin did not want women to take up roles that according to him were the sole domain of men. He thought that women should exclusively focus on the training of humankind, whereas men should be more practical in other matters.

Moreover, he weakens his own case by equating the division of roles between Ahlei-Ilm (scholars) and Ahl-e-siyasat (politician) with that of the division between the roles of men and women. While highlighting the failure of Ulema to understand the realities of the modern world, he himself does not understand that in today’s world both men and women are and should be responsible for the proper upbringing of their children and this role cannot and should not be ascribed to women alone. The same applies to social responsibilities in which women can work and are taking up responsibilities in nearly all fields of corporate and social lives.

Another recurring point in his articles and essays is the decline of Muslim societies. Discussing the decay of the Muslim world in history, Wahiduddin rightly points out that the moment when scholars and scientists lost their respect and value in society, the rot began. For example, he cites the decline of Muslim Spain and the dispersal of Muslim and Jewish intellectuals and researchers who had to flee from Spain to other Muslim states where they received short shrift.

The contemporary empires of the Mughals, Ottomans, and Safavid gave a cold shoulder to these newly arriving gems of Muslim intellect. The rulers in these empires were generally not much interested in experiments and inventions other than those which had direct and immediate benefits for the royal families and their companions.

Maulana Wahiduddin was inspired by the scientific and technological development in Europe and Western countries as he had read their history well. He lamented that the Mughals in India were too involved in incessant battles and wars, and mostly remained unaware and without any inspiration from the industrial revolution that was taking shape in Europe.

Particularly, he points out the lack of interest among the Mughals about establishing and using modern inventions such as the printing press.

To be continued

The writer holds a PhD from the University of Birmingham, UK and works in Islamabad.

Email: mnazir1964@yahoo.co.uk

-

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

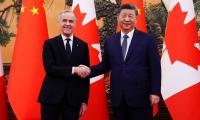

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training -

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light -

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push -

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down -

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career -

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer -

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis -

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI -

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds -

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years -

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome