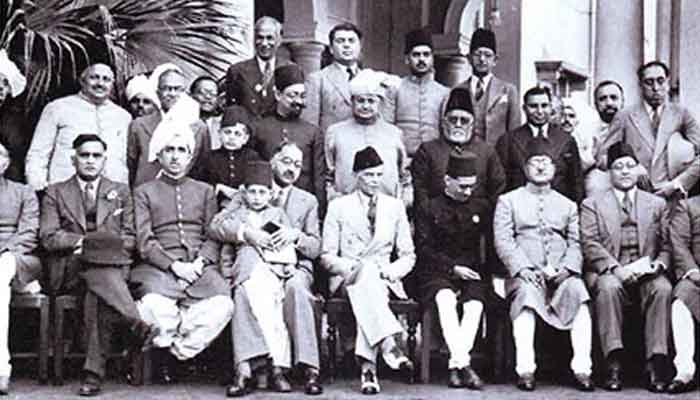

Iqbal, Jinnah and the Pakistan Resolution

23rd March is the day that commemorates the passage of the Pakistan Resolution by the Muslim League at its historic Lahore session in 1940. The Resolution was a major milestone in the struggle for independence. The Resolution formally made the demand for the independence of the Muslim majority areas of India as distinct entities, separate from the Hindus, and free from British colonial control.

The Resolution had yet seven years to go-ahead for the realisation of its objective. But it had a much longer context if one goes back into its history. The end of the Mughal rule, and the advent of the British, the Muslims’ state of despondency, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s role in addressing the plight through western education; the above culminating in the formation of the All India Muslim League.

The 1920s and 30s was a time of political turmoil in Indian politics. The Muslim League and Indian National Congress were leading the two major communities, with an acrimonious relationship. The Khilafat Movement and Nehru Report were the other catalysts bringing the Muslims to a national platform.

This Muslim sentiment received an impetus with and after the 1930 session of the Muslim League at Allahabad, where Mohammad Iqbal gave a call for a Muslim homeland, focusing on the northwest; this was to be within united India. Iqbal had been a champion of Indian nationalism, but his thought and poetry now celebrated Indian Muslim identity. This ‘idea’ would be given a name -Pakistan by Chaudhry Rehmat Ali. Interestingly, the three stakeholders, the British, Muslims and Hindus were moved by respective interests.

One problem was the lack of consensus among the general populace on the idea of a separate homeland; even many religious leaders differed on the idea. Mr Jinnah requested them to come forward to support it. It was left to Mr Jinnah to bring the Muslims together, on his return from Britain. In a poignant phrase used by Mr Akbar S Ahmad, he created ‘an all-India Muslim persona.’ The Muslim League membership grew, and it was able to do very well in the elections of 1945-46.

This was a reflection of the spirit Mr Jinnah had infused in the masses, now led by a motivated leadership.

The movement was now a Muslim movement for the attainment of a Muslim homeland. On the other hand, while the movement of the Hindus was Hindu in nature, it was couched in nationalistic terms; both aspects fused in issues relating to Bande Matram (Vande Mataram), and Gandhi’s idea of Ram Raj that created a chasm between the two communities.

The British were not aware of the storm that was gathering.

These ideas grew out of the Two-Nation Theory, advocated by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. Initially, he and leaders like Sir Mohammad Iqbal and Mr Jinnah believed that both the Muslims and the Hindus formed part of the Indian civilisation, meaning the civilisation of the subcontinent. In some ways, all had advocated Hindu-Muslim unity but had found it an exercise in vain. Developments of the early part of the 20th century convinced the Muslim leadership of the distinct identities, and separateness of the two ‘nations.’ This would lead Sir Iqbal to propose a partition in 1930. He proposed a ‘consolidated Muslim State’ that would be ‘in the best interests of India and Islam.’

His reasoning was politically sound, ‘to base a constitution on the conception of a homogenous India, or to apply to India the principles dictated by British democratic sentiments, is unwitting to prepare her for a civil war.’ These words echoed the thoughts of Mr Jinnah, and he reiterated these many times, in presenting the case for Pakistan. Jinnah and Iqbal met in London and were on the same page as far as a ‘separate homeland’ for the Muslims was concerned. The two leaders exchanged letters on such issues. Later on, under Mr Jinnah’s stewardship, this would translate into the independence of India.

Allama Iqbal, as a poet-philosopher, had a deep sense of history, and his political thoughts were based on insights from Indian history. Through his poetry and prose, he influenced the educated Muslims, as well as leaders like Mr Jinnah.

Thus he provided the inspiration to the motivation of Mr Jinnah for the independence movement. His address to the Allahabad session of the Muslim League was a prelude to the Lahore session that formally gave a call for Pakistan.

– The author is former faculty at Quaid-i-Azam University. He teaches in Karachi. The views expressed are his own.

-

Australia To Launch First High-speed Bullet Train After 50-years Delay

Australia To Launch First High-speed Bullet Train After 50-years Delay -

Meghan Markle Turns To Desperate Bids & Her Kids Are Her ‘saving Grace’: Here’s What They’ll Do

Meghan Markle Turns To Desperate Bids & Her Kids Are Her ‘saving Grace’: Here’s What They’ll Do -

King Charles Gives A Nod To Sister Anne's Latest Royal Visit

King Charles Gives A Nod To Sister Anne's Latest Royal Visit -

Christian Bale Shares Rare Views On Celebrity Culture Urging Fans Not To Meet Him In Person

Christian Bale Shares Rare Views On Celebrity Culture Urging Fans Not To Meet Him In Person -

Ariana Grande To Skip Actor Awards Despite Major Nomination

Ariana Grande To Skip Actor Awards Despite Major Nomination -

North Carolina Teen Accused Of Killing Sister, Injuring Brother In Deadly Attack

North Carolina Teen Accused Of Killing Sister, Injuring Brother In Deadly Attack -

Ryan Gosling Releases Witty 'Project Hail Mary' Ad With Sweet Reference To Eva Mendes

Ryan Gosling Releases Witty 'Project Hail Mary' Ad With Sweet Reference To Eva Mendes -

Teyana Taylor Reveals What Lured Her Back To Music After Earning Fame In Acting Industry

Teyana Taylor Reveals What Lured Her Back To Music After Earning Fame In Acting Industry -

Prince William Shows He's Ready To Lead The Monarchy Amid Andrew Scandal

Prince William Shows He's Ready To Lead The Monarchy Amid Andrew Scandal -

Lux Pascal Gushes Over Role In Tom Ford's 'Cry To Heaven': 'I Just Wanted To Be Part Of This Picture'

Lux Pascal Gushes Over Role In Tom Ford's 'Cry To Heaven': 'I Just Wanted To Be Part Of This Picture' -

Near-blind Refugee Found Dead In Buffalo After Release By US Border Patrol

Near-blind Refugee Found Dead In Buffalo After Release By US Border Patrol -

Firm Steps In Forcing Andrew’s Hand: ‘Can No Longer Keep A Promise'

Firm Steps In Forcing Andrew’s Hand: ‘Can No Longer Keep A Promise' -

Kenyan Man Accused Of Recruiting Men To Fight In Ukraine

Kenyan Man Accused Of Recruiting Men To Fight In Ukraine -

'The Wrong Paris' Star Veronica Long Shares What New Crime Series 'Blue Skies' Is About

'The Wrong Paris' Star Veronica Long Shares What New Crime Series 'Blue Skies' Is About -

King Charles Remains Immersed In Work Amid Andrew Scrutiny

King Charles Remains Immersed In Work Amid Andrew Scrutiny -

Bobby J. Brown's Passing Adds To Growing List Of Celebrity Deaths In 2026

Bobby J. Brown's Passing Adds To Growing List Of Celebrity Deaths In 2026