The past is never fully gone

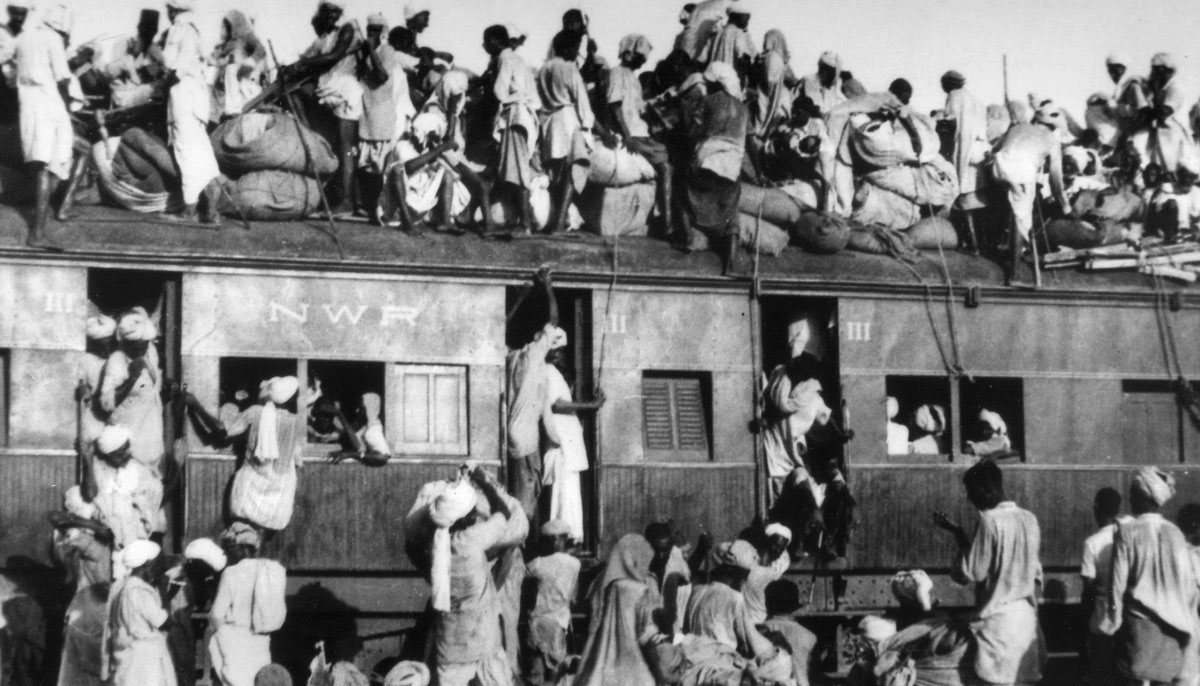

About 73 years ago, on August 14, 1947, a majority of the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent succeeded in the realisation of their dream of a separate homeland, where they could live freely and spend their lives according to their codes and wishes. The emergence of Pakistan as an independent sovereign state was a result of the relentless struggle of people from diverse backgrounds under the leadership of Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah. People from different creeds and ethnicities chose Pakistan over India due to its pluralistic and democratic character, and the insistence of the father of the nation on the equality of all citizens without any discrimination based on caste, creed or religion. It was this appeal to the ideals of justice, fairness, and equal opportunities in economic, cultural, and political matters that persuaded millions to support and sacrifice for the cause of Pakistan so that their descendants could live their lives without the fear of persecution or marginalisation.

Although the Pakistan Movement was overwhelmingly swayed by Islamic ardor, it was of a pluralistic persona religiously, ethnically, and linguistically. It was the principled politics of Jinnah and his promise of a democratic and secular state which lured people from varied backgrounds to the idea of Pakistan. Jinnah famously stated this democratic and secular spirit of Pakistan by saying:

“Democracy is in the blood of the Muslims, who look upon complete equality of mankind, and believe in fraternity, equality, and liberty,” and “You are free; you are free to go to your temples. You are free to go to your mosques or any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, caste or creed—that has nothing to do with the business of the state.” These pluralistic and secular ideals of Jinnah were amply reflected in the composition of the First Constituent Assembly of Pakistan.

However, this wishful optimism started to dwindle soon after independence. Among the earliest seeds of alienation was the issue of the national language of Pakistan. The newly independent dominion of Pakistan composed of two wings; Eastern and Western. The Eastern Wing (East Bengal) was predominantly composed of the Bengali population with Bangla as their native language. Western Wing was geographically comprehensive with an ethnically and linguistically diverse people. Despite this disparity of size, the Eastern Wing had a larger population as compared to Western Wing. Ignoring the fact that a dominant majority of the new dominion used Bangla as their primary mode of education and communication, Urdu ordained as the exclusive national language sparking a widespread discontent among the majority Bengali-speaking population. This act of unilateral imposition of Urdu as the only national language and snubbing the native voices led to a mass Bengali Language Movement, which demanded that along with Urdu, Bangla also be recognized as a national language. The upcoming years witnessed mass protests and agitations with the government resorting to the use of force. These tensions continued until 1956 when the central government finally acknowledged Bangla as an official language. The mishandling of the language issue with narrow nationalism proved disastrous for the newly-independent dominion while alienating the dominant majority and strengthening the assertion of Bengali national identity.

Facing difficulties in managing the affairs of two separate wings with disparities in population and geographic terms and with an enemy in between, the Government of Pakistan introduced the “One Unit” policy in 1954 to redress and mitigate the differences among two regions. Under this program, the four provinces of the eastern wing merged to single territory West Pakistan, parallel to East Pakistan. Substantiating the benefits of the “One Unit” program, the then-Prime Minister Muhammad Ali Bogra maintained:

“There will be no Bengalis, no Punjabis, no Sindhis, no Pathans, no Balochis, no Bahawalpuris, and no Khairpuris. The disappearance of these groups will strengthen the integrity of Pakistan.” This policy remained unable to achieve its stated objectives and social grievances keep on exacerbating under the military rule. Further the concocted defeat of Mohtarma Fatima Jinnah, who was the candidate of all opposition parties combined, in 1965 presidential elections further alienated the already divided polity. With increasing political pressures, the “One Unit” policy was ultimately dissolved by the then-President General Yahya Khan in 1970 and, the original status of the provinces restored though it was too late.

The friction between separate geographic wings, which started with the language controversy in 1948, ultimately culminated in East Bengal becoming an Independent Bangladesh in 1971. Although people from East Bengal played a pivotal role in the Pakistan Movement, it was the issues of social, cultural, political, and economic mismanagement and discrimination that alienated the majority Bengalis. The Bengalis initially claimed their due rights and representation within Pakistan but, failing to achieve led to the demands of separation. Present-day Pakistan might have been different and, the debacle of 1971, might have been avoided if the urging of devolution of powers cultural recognition had dealt with pragmatism.

Nevertheless, from the reigns of the 1971 tragedy, Pakistan stood firm with the making of the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan. It was the first constitution unanimously drafted by the elected representatives and gave Pakistan a character of a parliamentary republic. Constitution injected a new hope for the people of Pakistan as it tried to redress the long-lasting issues of representation and distribution among the federating units. Standing on its feet, Pakistan emerged as a leader of the Muslim world and a broker of peace at the global stage. But this merriment was evanescent as Pakistan endured another military coup led by General Zia-ul-Haq. Since then, these hopes have continuously been shattered, with intermittent military interventions and altering of the original charter of the constitution by the myopic leadership.

Passing from this adventurism, the 18th Constitutional Amendment in 2010 finally rejuvenated the essence of the 1973 Constitution transforming Pakistan, back to a parliamentary republic from a semi-presidential system and eliminating the presidential powers to unilaterally, dissolve the assemblies. Along with this, the enduring demands of provincial autonomy were also addressed as many ministries devolved including, health, education, environment, and tourism, etc. The passing of the 18th Amendment was a heyday for the democrats as it strengthened the constitution and the federation by permanently closing the doors to military adventurism and upheld the ideals of provincial autonomy addressing the issues of representation and redistribution. But these changes seem not to be welcomed by certain quarters who erroneously consider provincial sovereignty a threat to national unity. A recent episode in this regard is the introduction of the “Single National Curriculum” policy with a slogan of “One Nation One Curriculum,” which is being considered as the transgression of the 18th Amendment on the part of the federal government because education policy is the domain of provinces.

Nationalism in Pakistan has narrowly attributed to uniformity and singularity based on religion and, it has served the political purposes of nationalism. But these homogenizing projects have been proved destructive around the world, including Pakistan and, the case of Bangladesh is a classic example.

The definitions and dimensions of nationalism and nationhood keep on changing with the changing character of politics and the international environment. Nationalism may take on new forms in which nation-state is no longer central but rather the demands of devolution of power and cultural recognition. Nationalist politics is frequently represented as ethnic politics but, contemporary nationalism comes to focus less on appeal for political independence and more on cultural acknowledgment and affirmative action. The history of Pakistan amply contains the examples where initial demand of social, cultural, and political recognition and just distribution of resources remained unheard, they led to more political segregation and ultimately to the movement for independence, in the case of Bangladesh.

The ethnic, racial, and linguistic diversity is what states make of it. States can turn these resources against them or use them for the uplift and development of the whole nation. There is this need for self-introspection to shatter our myopic nationalist tendencies as these are short-lived and disastrous. The Constitution of Pakistan and its 18th amendment need to be executed and celebrated in letter and spirit as it seems the best available option till now, which respects the cultural and ethnic diversity of millions of Pakistanis. Centralisation is not a dependable policy for a strong sense of nationhood. Many developed countries practice decentralised system, respecting the cultural and ethnic differences of their populace, and yet they exhibit a strong sense of civic-nationalism and nationhood.

Pakistan is a resilient nation. Despite all the internal issues of political representation and distributive justice, when faced with the challenge of conventional external aggression or non-conventional terrorism, the country left no stone unturned in the fight against the enemy. It was this determinism and faith of the people that Pakistan remained steadfast in the face of the plethora of challenges, be it economic crunch, Indian aggression, Bengal’s secession, the war on terrorism, or the fight against novel coronavirus.

If we acknowledge our differences, practice pluralism, and cherish our cultural diversity, the trends which seem to be state-subverting, will turn to the state strengthening nationalism. It is only possible if we have faith in our people as the founder of the nation believed: “With faith, discipline and selfless devotion to duty, there is nothing worthwhile that you cannot achieve.”

—The writer is a graduate of SPIR-QAU and IUIC and teaches International Relations at IIU, Islamabad. He can be reached at hassan.spir@gmail.com.

-

Prevent Cancer With These Simple Lifestyle Changes

Prevent Cancer With These Simple Lifestyle Changes -

Experts Reveal Keto Diet As Key To Treating Depression

Experts Reveal Keto Diet As Key To Treating Depression -

Inter Miami Vs Barcelona SC Recap As Messi Shines With Goal And Assist

Inter Miami Vs Barcelona SC Recap As Messi Shines With Goal And Assist -

David Beckham Pays Tribute To Estranged Son Brooklyn Amid Ongoing Family Rift

David Beckham Pays Tribute To Estranged Son Brooklyn Amid Ongoing Family Rift -

Jailton Almeida Speaks Out After UFC Controversy And Short Notice Fight Booking

Jailton Almeida Speaks Out After UFC Controversy And Short Notice Fight Booking -

Extreme Cold Warning Issued As Blizzard Hits Southern Ontario Including Toronto

Extreme Cold Warning Issued As Blizzard Hits Southern Ontario Including Toronto -

Lana Del Rey Announces New Single Co-written With Husband Jeremy Dufrene

Lana Del Rey Announces New Single Co-written With Husband Jeremy Dufrene -

Ukraine-Russia Talks Heat Up As Zelenskyy Warns Of US Pressure Before Elections

Ukraine-Russia Talks Heat Up As Zelenskyy Warns Of US Pressure Before Elections -

Lil Nas X Spotted Buying Used Refrigerator After Backlash Over Nude Public Meltdown

Lil Nas X Spotted Buying Used Refrigerator After Backlash Over Nude Public Meltdown -

Caleb McLaughlin Shares His Resume For This Major Role

Caleb McLaughlin Shares His Resume For This Major Role -

King Charles Carries With ‘dignity’ As Andrew Lets Down

King Charles Carries With ‘dignity’ As Andrew Lets Down -

Brooklyn Beckham Covers Up More Tattoos Linked To His Family Amid Rift

Brooklyn Beckham Covers Up More Tattoos Linked To His Family Amid Rift -

Shamed Andrew Agreed To ‘go Quietly’ If King Protects Daughters

Shamed Andrew Agreed To ‘go Quietly’ If King Protects Daughters -

Candace Cameron Bure Says She’s Supporting Lori Loughlin After Separation From Mossimo Giannulli

Candace Cameron Bure Says She’s Supporting Lori Loughlin After Separation From Mossimo Giannulli -

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Are ‘not Innocent’ In Epstein Drama

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Are ‘not Innocent’ In Epstein Drama -

Reese Witherspoon Goes 'boss' Mode On 'Legally Blonde' Prequel

Reese Witherspoon Goes 'boss' Mode On 'Legally Blonde' Prequel