Partition narrative: Journey to Pakistan

Wikipedia defines a narrative as ‘an account of a series of related events, experiences, whether true or fictitious.’ In simple words, it is something that is narrated. In recent times, the narrative has become a popular term in political and journalistic lexical. As the nation celebrates its 73rd Independence Anniversary, it is instructive to look at—or back—at the ‘narrative’ of Independence that ponders over ‘series of related events, and experiences,’ mostly before Independence. (In non-academic context, the term Partition has been in common usage; in this context, Partition is the action or state of dividing or being divided into parts.)

Independence Day appears to be an opportunity to take a critical look at this milestone with the benefit of hindsight. Today, this exercise helps in two ways: to put into context the turmoil the nation sees itself in, in terms of the political system, institutions, and the loss of values, and the low we witness in relations with India; can be studied in the context of the ‘Independence narrative.’ Pakistan and India have shared a common history as part of British India and have been uneasy neighbours; like the Independence movement, this narrative cannot be studied divorced from the ‘Indian’ context.

The Independence movement can be regarded as a series of events for about five decades. Some would see it as the emergence of Hindu-Muslim differences, and the realisation of Muslim identity, and an effort to preserve it—all leading to conflict. The British rule provided a context for this; Separate Electorates, 1909, annulment of Partition of Bengal, 1911, the Rowlatt Act, among many developments, are defining moments that exacerbated these differences and sharpened communal attitudes. The foundation of the Muslim League in 1906 was a major milestone in providing the Muslims an organisational umbrella. It drew inspiration from charismatic leaders like Nawab Salimullah Khan, Mohsin ul Mulk, and Sir Agha Khan; the nationalist poetry of philosopher Muhammad Iqbal would act as a catalyst.

After 1919, the Hindus and Muslims were contenders for power, as the two organised into political communities under the political labels of the Indian National Congress and All India Muslim League, respectively. The Allahabad session of the Muslim League became a milestone where Allama Iqbal, in his Presidential Address, extrapolated the idea of a Muslim state in India, a revolutionary idea at that time. The Muslims all over India rallied behind this call that was soon given the name Pakistan by Chaudhry Rehmat Ali.

While Pakistan became a clear goal, the hurdles on the way were many. Besides the colonial yoke, the uncompromising attitude of the Hindus led to a bumpy road ahead. One illustration of this was the elections of 1935, and the Hindu policy not to share ministries with the Muslims. It is pertinent to steer that the core division was the politico-religious division between the two communities—the Muslim League leading the Muslims and the Congress while professing to represent the Indians, catering to the interests of the Hindus, and nullifying those of the Muslims. One could see the seeds of the future.

The issue of Babri mosque, cow slaughter, consumption of beef, religious belief would lead to conflict, and the hostility would lead to violence against the Indian Muslims. These were few of the differences highlighted by Mr Jinnah in his address at the historic session of the Muslim League at Lahore, classifying Muslims and Hindus as two nations. What he explained was not rhetoric but the political reality of India that some people took lightly. Based on the Two-Nation Theory that the Hindus rejected at the time, it has a resonance eight decades on and reinforces the Independence narrative. But this provided further impetus to the Independence struggle. What transpires today in terms of hostility and bitterness between the two neighbours can be explained in terms of ‘Two nations’ philosophy.

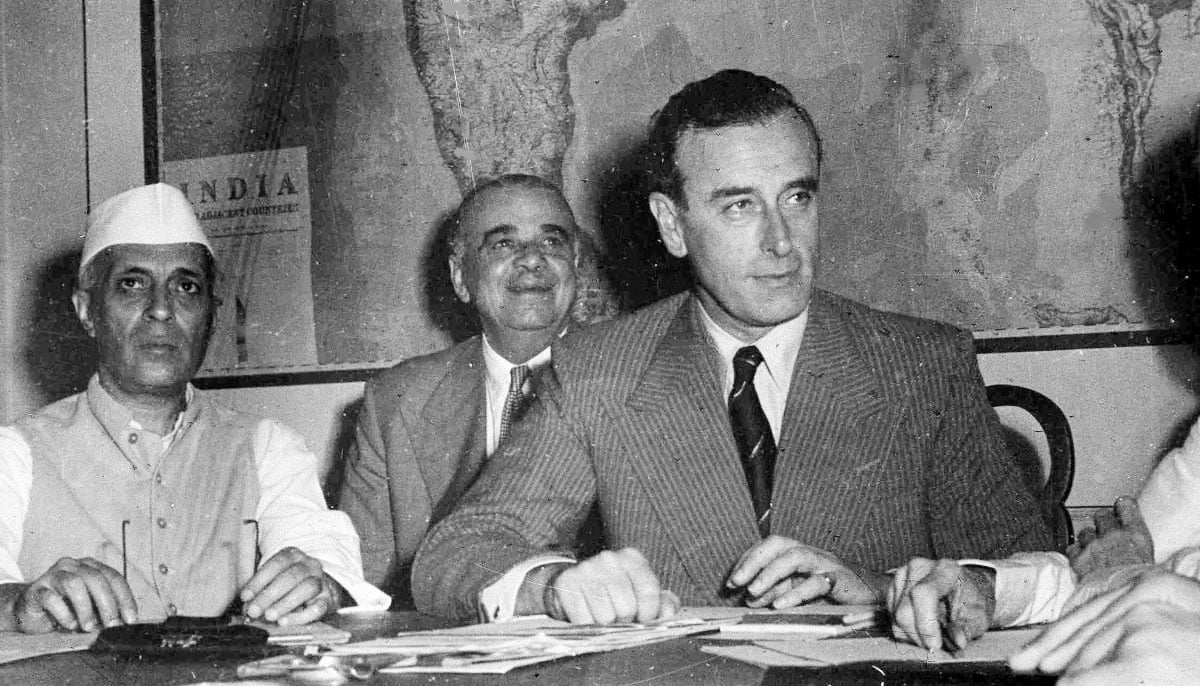

The role of leadership comes out very strongly on both sides. While having the advantage of being closer to the British, Hindu leadership felt they were the stronger party. But, Mr Jinnah and his western ways, straight forward style, and legal training was a perfect match to counter the Congress’ moves to undermine the Muslim cause. The Muslim League leaders remained committed to the cause of Pakistan, more so after the Lahore session of 1940. They had to fight on two fronts, the Congress and the colonial government. Still, through their ingress in British circles, Congress leaders managed to have unfair advantages, as in the case of the Radcliffe Award.

The Accession of Kashmir to India would become a travesty of the Partition settlement and unfinished business. The post-Partition narratives focused on persona travails of the migrants, and issue emerging division management. Kashmir issue dominated the narrative in the early years. The situation obtaining there since last August has added to the miseries of the people blatantly deprived of their civil rights, with no redress adds another painful dimension to the narratives. Present-day India reflects the Hindu-Muslim differences that drew the two communities apart in the early twentieth century and led to violence and misery at the time of Partition. It is a historical legacy that the successor states were unable to manage or seriously address, leading to a virtual standoff in bilateral relations today.

The scenes of people migrating on carts, on foot, and astride cattle give a poignant touch to the Partition narrative, the segments related to migration shown on media on Independence Day, bring painful memories to those who went through those times and lost their dear ones in the ongoing violence. The dominant theme on a personal level has been the loss and losses, besides identity; at the national level, it has been striving and survival. Memories fade with time, a sketchy account is presented by Anam Zakria in The Footprints of Partition, and in the past by authors like Qudratullah Shahab, Khushwant Singh, among others. The narrators could be seen as the ‘lost generation.’ This generation keeps the narrative alive about a personal loss, sacrifice, and transplantation.

While this (personal) narrative is growing weaker, the core narrative of the Partition—its raison d’etre and the struggle to survive remains alive; the Indian moves, diplomatic and communal, give it sustenance. As the Indian lockdown in Kashmir completes its one year, the narrative is strengthened, in terms of an unjust dispensation, and continued resentment. Scenes of migrating families and communal violence that become alive on Independence Day are real for many on both sides. The Partition narrative embedded in the national psyche and culture remains an important factor in national cohesion.

-The writer is former faculty, Area Study Center, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad

-

Czech Republic Supports Social Media Ban For Under-15

Czech Republic Supports Social Media Ban For Under-15 -

Prince William Ready To End 'shielding' Of ‘disgraced’ Andrew Amid Epstein Scandal

Prince William Ready To End 'shielding' Of ‘disgraced’ Andrew Amid Epstein Scandal -

Chris Hemsworth Hailed By Halle Berry For Sweet Gesture

Chris Hemsworth Hailed By Halle Berry For Sweet Gesture -

Blac Chyna Reveals Her New Approach To Love, Healing After Recent Heartbreak

Blac Chyna Reveals Her New Approach To Love, Healing After Recent Heartbreak -

Royal Family's Approach To Deal With Andrew Finally Revealed

Royal Family's Approach To Deal With Andrew Finally Revealed -

Super Bowl Weekend Deals Blow To 'Melania' Documentary's Box Office

Super Bowl Weekend Deals Blow To 'Melania' Documentary's Box Office -

Meghan Markle Shares Glitzy Clips From Fifteen Percent Pledge Gala

Meghan Markle Shares Glitzy Clips From Fifteen Percent Pledge Gala -

Melissa Jon Hart Explains Rare Reason Behind Not Revisting Old Roles

Melissa Jon Hart Explains Rare Reason Behind Not Revisting Old Roles -

Meghan Markle Eyeing On ‘Queen’ As Ultimate Goal

Meghan Markle Eyeing On ‘Queen’ As Ultimate Goal -

Japan Elects Takaichi As First Woman Prime Minister After Sweeping Vote

Japan Elects Takaichi As First Woman Prime Minister After Sweeping Vote -

Kate Middleton Insists She Would Never Undermine Queen Camilla

Kate Middleton Insists She Would Never Undermine Queen Camilla -

King Charles 'terrified' Andrew's Scandal Will End His Reign

King Charles 'terrified' Andrew's Scandal Will End His Reign -

Winter Olympics 2026: Lindsey Vonn’s Olympic Comeback Ends In Devastating Downhill Crash

Winter Olympics 2026: Lindsey Vonn’s Olympic Comeback Ends In Devastating Downhill Crash -

Adrien Brody Opens Up About His Football Fandom Amid '2026 Super Bowl'

Adrien Brody Opens Up About His Football Fandom Amid '2026 Super Bowl' -

Barbra Streisand's Obsession With Cloning Revealed

Barbra Streisand's Obsession With Cloning Revealed -

What Did Olivia Colman Tell Her Husband About Her Gender?

What Did Olivia Colman Tell Her Husband About Her Gender?