The dismissible

When an event is unexplained, it can’t be repeated. Cuba’s astonishing internationalism, the “good news” of the pandemic, is talked about (outside Cuba) as if a miracle, without cause. Support grows for the Nobel Prize nomination but the justification for the Henry Reeve Brigade, established in 2005, is left out. The explanation is ideas.

It is urgent according to Eddie Glaude in a new book on James Baldwin. Well, he doesn’t exactly say that. But for Baldwin, “what kind of human beings we aspire to be” is most important and the explanation for Cuba’s success is precisely that. In Zona Roja, Enrique Ubieta Gómez says Cuban medical workers – fighting Ebola in 2014 – know about existence: We exist interdependently. Ubieta describes Cuban internationalism as an “inescapable ethic”. Once you’ve lived it, you cannot not live it. You know human connection – a fact of science – and you learn its energy.

Ubieta’s explanation is existential. Baldwin used similar language. In 1963, he wrote, “Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we … imprison ourselves … to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.” Glaude supports Baldwin’s call to “begin again”, with the “America idea”, shedding its “old ideas”. He might look South. Latin American independistas raised precisely Baldwin’s question: how to resist the “lie at the heart of the [imperialist] nation” when it is about “love, life and death”, that is, everything.

Truth is not enough. If Galileo had just provided truths, he wouldn’t have been condemned. Galileo became threatening when he made those truths plausible with a larger picture of “cosmic humility”, contradicting the establishment’s comforting identity. One thing we might learn from Galileo, according to astrophysicist Mario Livio in a new book, is that he didn’t just observe truths and tell stories about them. His “phenomenal capacity for abstraction” let him see where those truths led.

Truths are easy when unexplained. Consider Olga Tokarczuk’s 'Flights'. It gives truth about people traveling everywhere “escaping their own lives, and then being safely escorted right back to them”. We see people running through airports with “flushed red faces, their straw hats and souvenir drums and masks and shell necklaces”. All this “moving around in a chaotic fashion … [to] increase their likelihood” of being in the “right place at the right time” even has meaning. A “travel psychologist” explains that such chaos “appears to call into question the existence of a self understood non-relationally”.

It is funny to expect deeper meaning regarding people “moving around in a chaotic fashion” to increase their likelihood of being in the right place at the right time from a “travel psychologist” at an airport between flights. We laugh because we do in fact expect that, absurdly.

We get truth from 'Flights' but it’s dismissible. Annushka, for instance, escapes her unbearable life : to “go, sway, walk, run, take flight”. She finds happiness when “she does not have a single thought in her head, a single care, a single expectation or hope.” She’s “happy”, free of her identity, her life, her responsibilities. But she is also cold, hungry, dirty, alone, tired, and homeless. The image is silly.

In fact, the idea underlying it is silly, namely, that to have no thoughts, you should have no identity, no responsibilities. It’s as pervasive as friction, from which Galileo abstracted to get truth about inertia. In fact, to be happy with no expectations or hope, as Annushka is, is not silly. But understanding how that is so requires a “phenomenal capacity for abstraction” from social expectations.

'Flights' doesn’t do that. It responds to an expectation identified by Cuban philosopher and diplomat Raul Roa in 1953 as the “world’s gravest crisis”. It was indeed the “America idea”: Human beings imprisoned in discrete selves, defined by action and results. It is not humanist, as claimed, Roa argues, because it omits “the fact of death”, as Baldwin recognized. There were “few dissenters” to the “man of action” during the Renaissance, and Roa saw there would now be none because of US power.

Baldwin tried to escape that power by living outside the US. He struggled with what it had “made of him”. But “American power follows one everywhere”.

Emily Dickinson, “the greatest poet in the English language”, abstracts from expectations 'Flights' dignifies. According to biographer Martha Ackman, Dickinson lived as if busyness and travel is not progress. She never apologized for, nor defended, the priority she gave to silence and solitude. As result, we get truth from her poetry: about what it means to be human. For, she was in fact not detached from a world she never visited physically or had any desire to.

She lived as if isolation and detachment are not synonymous. But to know where this leads, you must abstract from the “America idea” that equates human worth and utility. Comfortably, though, Dickinson is odd – “America’s most enigmatic and mysterious poet” – and her way of life therefore dismissible.

'Lord of all the Dead', like 'Flights', leaves comforting “old ideas” in place. Javier Cercas tells the story of his great-uncle who fought a “useless war” for Franko. His memoire does give truth but doesn’t explain it, so his story, which for him is just a story, cannot itself explain, and is dismissible.

Achilles in 'The Odyssey' is “lord of all the dead” because he died young and beautiful, and gained immortality. That his great uncle was “politically mistaken, there’s no doubt.” But was he a human failure? Cercas’ answer is no. At one level, Cercas rejects the Greeks’ ideal of “beautiful death” because it denies the existential reality of decrepitude: There is no escaping it. But on the other hand, Cercas assumes the separation of mind and body that makes “beautiful death” worth speculating about: the idea that the body decays and that the mind somehow escapes nature’s universal laws of causation.

He ends the book speculating about immortality. Nobody dies, he writes. We’re just transformed, physically. He himself, at the book's end, is in the “eternal present”. It doesn’t explain what needs to be explained, given the real story of this book which is what Cercas calls the “silent wake of hatred, resentment and violence left over by the war”. The “silent wake” is explained by ignorance precisely of shared humanity Cercas names but doesn’t explain. It is decrepitude: “the fact of death”.

It is known by every human being. Cercas tells a story about his great uncle but denies the significance of that story because he tells it with the “old ideas” in place, the ones Glaude says need to be shed, like “swaddling clothes” to “begin again” as Baldwin urged. Glaude is not sure it can happen. But it has happened. That’s the “good news” about the Henry Reeve Medical brigade, if it were explained.

On Friday, March 20, Cuban president, Miguel Diaz-Canel, speaking nationally, outlined new measures to slow the pandemic. The good news, he said, is that Cuban people supported the decision to accept the Braemar, a UK cruise ship refused docking elsewhere because of infected passengers. A century ago, another ship sought aid from Cuba. Its passengers were Jews. It was turned away.

That, Diaz-Canel said, was before the Revolution. The good news was the expectation that the Braemar should be helped. That expectation is the success of the Cuban revolution. It explains the Henry Reeve Brigade. Expectations come from practises, from what is lived. Diaz-Canel then said, “one day the truth will be known.” But what truth?

Excerpted from: 'Cuba’s Nobel Nomination and Baldwin’s Call to “Begin Again'.

Courtesy: Counterpunch.org

-

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss -

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning -

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding -

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border -

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene -

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce -

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All'

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All' -

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals -

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked -

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

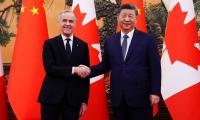

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training