The subtle art of getting it right

The PM’s efforts to make Kashmir a live issue on the diplomatic stage have seen a surge in his popularity at home. But two statements by Imran have been especially important in laying out Pakistan’s calculus before the region.

Before leaving for New York, the PM told media reporters that anyone crossing over from Pakistan to fight would be an enemy of both Pakistan and of Kashmiris. Later, he reiterated another warning to Kashmiris not to cross the Line of Control.

This shift cannot be overstated, and should not be taken for granted. This past decade, governments that have sought to rehabilitate Pakistan’s image have had to reckon with the perverse incentives of the 1980s that haemorrhaged the country of international goodwill and investor confidence, even as late as the Abbottabad raid in 2011.

After 2011, three inflection points made it both urgent and necessary that the state’s core functions be reset. The first was the December 2014 APS Peshawar attack that turned public opinion in Pakistan against the Taliban, and forever changed the demands that Pakistanis would made of their state.

The second inflection point came in June 2018, when Pakistan made a high-level political commitment to work with the FATF to address its strategic counter-terrorism financing-related deficiencies.

The third knock was delivered in May 2019, when India’s election results confirmed South Asia to another five years of belligerent, Hindutva revisionism, and with it, hard choices for a Pakistani state.

For Pakistan, each of these events spurred introspection that, for the first time since 2011, fed systematically into sober policy reform.

The Peshawar massacre was followed by an unprecedented 15-point National Action Plan to weed out domestic extremism, much of which later informed the ruling PTI’s election platform. The brush with the FATF led to the arrests of individuals linked to the Mumbai attacks, and the banning of charities linked with proscribed militant organizations. Anti money-laundering and counterterror financing measures taken by Islamabad are now being shared through a series of comprehensive compliance reports.

Finally, the re-election of Modi in 2019, as explained by the PM at the Asia Society in New York, was followed by perhaps the most concerted and institutionalized outreach ever by the Pakistani state to New Delhi, to mend bridges and jointly tackle the shared challenges of poverty and climate change.

These three deliberate choices by the state, though prompted by less-than-ideal circumstances, were nonetheless organic in their promulgation. They were all oxygenated by broad-based domestic support, and conspicuously rooted in a need to reframe the raison d’être of the state as one focused on domestic welfare, social justice, and economic recovery.

And so when on the morning of August 5, the Indian occupied state of Jammu & Kashmir found itself in virtual lockdown, the pushback from Islamabad was unified, democratic and institutionalized, all of which in turn helped grease the Foreign Office’s advocacy wheels abroad.

But as the crackdown in Kashmir enters its ninth week, it is worth asking whether the shifts brought about by these aforementioned inflection points have aggregated in way that can now meaningfully produce international dividends. Put differently, is the creeping international attention over Kashmir because of the incredible intelligibility with which Pakistan has been able to express its position on Kashmir since August 5, or in spite of it?

The answer is: both. So far, the singular message from Islamabad, on escalation risk as well as the right of Kashmiris to self-determination, has both steadied and re-enforced a global message. Faced with the possibility of the Kashmiri curfew gestating into a full-blown genocide, the PM’s meeting with the editorial board of the NYT resulted in a stinging editorial that went beyond raising concerns on human rights abuses by calling on the United Nations Security Council to intervene in the bilateral dispute.

Starting with the White House, the receptivity of Pakistan’s message has only been made possible because Pakistan had, prior to August 5, unambiguously disavowed the use of non-state actors. Pakistani officials have publicly and privately maintained that regional stability is a necessity and not a luxury, and insisted that the state’s job should be that of a net-provider of domestic welfare including climate action. And one significant but little noticed impact of the policy shift in Islamabad has been the near absence of right-wing umbrella organizations such as the Difa-e-Pakistan Council, or jihadi groups such as the JuD, taking to the streets for the Kashmir cause.

Without this reframed idea of the state, it is unlikely that Pakistan would have been able to convincingly attract bipartisan attention to Kashmir in the United States, or persuade even friendly international takers – Turkey, China and Malaysia – that the biggest danger to peace and stability in South Asia now stems from an aggressive ultranationalist regime in New Delhi.

While India continues to maintain that Pakistan’s raison d’être is one that trades instability abroad for legitimacy at home, Pakistan’s role in frantically trying to deliver an endgame that can bring a 17-year war in Afghanistan to the end is, for the first time, seeing public acknowledgement in the US. Other accusations by India are similarly untenable, given that steps by Pakistan against militant organizations are now verifiable by third parties.

But it would also be wrong for Pakistan to think that the international bloom is off the rose as far as Prime Minister Modi’s approach to democracy and human rights are concerned. The sheer breadth of Indo-US ties was on naked display in Prime Minister Modi’s rapturous welcome in Houston. The shadow of violence in Kashmir did not prevent India from enjoying a solid diplomatic run in New York on the sidelines of UNGA, and again last week when India’s MEA descended in Washington to work the think-tank circuit.

The lesson for Pakistan from all of this is that narratives devoid of legitimacy have an easy-to-use kill switch. It helps that Pakistan hosts one of the world’s oldest peacekeeping missions – UNMOGIP; India prevents the group from visiting its side of the Line of Control.

But staying on-message will only be possible if we ensure that our message is backed by democracy, tolerance for dissent, economic growth and progressive statehood at home – objectives forgone by the increasingly reckless polity next door.

The writer is a PhD candidate at Yale.

Twitter @fahdhumayun

-

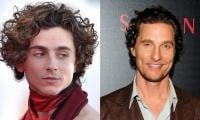

Timothee Chalamet Shares Major Learnings After Working With 'favourite' Director Christopher Nolan

Timothee Chalamet Shares Major Learnings After Working With 'favourite' Director Christopher Nolan -

Timothee Chalamet Heaps Praise For Matthew McConaughey's Work In Super Hit Project 'Interstellar'

Timothee Chalamet Heaps Praise For Matthew McConaughey's Work In Super Hit Project 'Interstellar' -

British MPs Pass A Motion Due To Andrew: ‘Lets Remove The Bandages From Our Mouths

British MPs Pass A Motion Due To Andrew: ‘Lets Remove The Bandages From Our Mouths -

Prince Edward Forced To Skip Royal Engagement With King Charles

Prince Edward Forced To Skip Royal Engagement With King Charles -

Sharon Osbourne Says Ozzy Osbourne 'knew' He Could Die Ahead Of Last Black Sabbath Show

Sharon Osbourne Says Ozzy Osbourne 'knew' He Could Die Ahead Of Last Black Sabbath Show -

Telegram Co-founder Pavel Durov Under Investigation: Russian State Media

Telegram Co-founder Pavel Durov Under Investigation: Russian State Media -

Ethan Hawke On Regrets He Had Related To Daughter Maya Hawke: 'Really, Really Hard'

Ethan Hawke On Regrets He Had Related To Daughter Maya Hawke: 'Really, Really Hard' -

Here's What 'Lizzie McGuire' Alum Jake Thomas Said About On Screen Dad Robert Carradine Ahead Of Death

Here's What 'Lizzie McGuire' Alum Jake Thomas Said About On Screen Dad Robert Carradine Ahead Of Death -

Nvidia Earnings Face AI Boom Test Amid Intensifying Market Competition

Nvidia Earnings Face AI Boom Test Amid Intensifying Market Competition -

UK Government Sign Off On Releasing Confidential Documents About Andrew: Here’s Why Now

UK Government Sign Off On Releasing Confidential Documents About Andrew: Here’s Why Now -

David Bowie's Daughter Alexandria Lexi Jones Recalls Painful Childhood Trauma: 'That Is Abuse'

David Bowie's Daughter Alexandria Lexi Jones Recalls Painful Childhood Trauma: 'That Is Abuse' -

Prince Harry Speaks Directly To Ukraine In An Emotional Statement: Watch

Prince Harry Speaks Directly To Ukraine In An Emotional Statement: Watch -

Kelly Clarkson Gushes About 'The Voice' Contestants' Sweet 'gift': 'You Are My Favorite'

Kelly Clarkson Gushes About 'The Voice' Contestants' Sweet 'gift': 'You Are My Favorite' -

Kelly Clarkson Recalls Facing Prejudice From Music Execs After Winning 'American Idol' In 2002

Kelly Clarkson Recalls Facing Prejudice From Music Execs After Winning 'American Idol' In 2002 -

Demi Lovato Thought She Was 'maxed Out On Love' For Jordan 'Jutes' Lutes On Wedding Day

Demi Lovato Thought She Was 'maxed Out On Love' For Jordan 'Jutes' Lutes On Wedding Day -

Director Of UK Airline Parts Firm Jailed Over $9m Fraud

Director Of UK Airline Parts Firm Jailed Over $9m Fraud