Mainstreaming madrasas a distant dream despite efforts of two decades

For two decades, the Pakistani authorities have been trying to regulate madrasas under the federal education ministry but no success has so far been achieved in this regard as the key problems of the allocation of funds to madrasas, their curriculum and the legal status of madrasa certification are yet to be addressed.

The fault apparently lies with the government as the madrasas’ bodies of the country are willing to be regulated. The largest association of seminaries in the country, the Ittehad-e-Tanzeemat-e-Madaris Pakistan (ITMP), which was established in 2005, has called for mainstreaming the madrasas in the country.

In 2010, the ITMP signed an agreement with the government on behalf of its five constituent boards, the Wafaq-ul-Madaris Al-Arabia, the Tanzeem-ul-Madaris Ahl-e-Sunnat, the Rabita-ul-Madaris Al-Islamia, the Wafaq-ul-Madaris Al-Salfia and the Wafaq-ul-Madaris Al-Shia.

These boards operate thousands of madrasas of various Islamic schools of thought across the country. It is a positive signal that they want to mainstream the education at seminaries and teach non-religious subjects such as sciences along with the religious subjects to their students. The authorities concerned, however, are reluctant to make a clear decision to mainstream the madrasas and come up with a proper mechanism for that.

The government has rather complicated the governance of madrasas as currently three federal ministries – the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Interfaith Harmony, the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training – are dealing with the seminaries with no distinct boundaries of their intervention in the administrative affairs of the madrasas. With three ministries having their say in the issues of madrasas, the management of the seminaries are in utter confusion.

Unfulfilled vows

Under the 2010 agreement, the federal government and the ITMP had agreed on including the compulsory subjects of the mainstream educational boards in the syllabi of madrasas. It was also decided that the five constituent madrasa boards of the ITMP would have the legal right to issue certificates of matriculation and intermediate after they were regularised.

It was also agreed that the madrasa boards would be recognised as educational boards through a parliamentary act or an executive order to link them with the ministry of education. Another vow made in the agreement was that the government would appoint two nominees to achieve uniform standard of education at the seminaries.

“This accord was an important national document for ensuring religious harmony in the country. While the government could have also introduced similar curricula in madrasas to minimise sectarian differences among various sects of Muslims but no such measures have been taken so far,” said Sabookh Syed, an Islamabad-based journalist who covers religious affairs.

Syed says: “Introducing formal education at madrasas was not a strenuous task because around all the religious seminaries already have basic facilities like building, water, electricity, toilets, and others. Also, a majority of seminaries’ teachers can teach many subjects including Urdu, Pakistan studies, Islamic studies and other arts subjects.”

However, the agreement could not be actualised and the idea of mainstreaming the madrasas turned out to be a pipe dream. “Unluckily, the agreement between the ITMP and the federal government proved to be a piece of paper and no serious efforts were made by the federal government for its implementation,” said former Pakistan Madrasah Education Board chairman Dr Aamir Tuaseen.

Mushrooming growth

According to Prof Dr Tauseef Ahmed Khan, a retired teacher of journalism, the mushrooming growth of madrasas happened in the country during the dictatorship of Gen Ziaul Haq under his Islamisation mission.

“In the 1980s, madrasas were funded by the United States and the Arab countries to radicalise religious education for fueling Afghan Jihad. Also, Jihadi clerics were encouraged to glorify Jihad at seminaries for Afghan-Soviet War. This trend remained until the Taliban government in Afghanistan was toppled in 2001 after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Centre,” Dr Khan said.

He added that in the post-9/11 era, law enforcement and security agencies of the country felt the need to keep hardliner clerics and their madrasas under surveillance and the government pressed the seminaries to get themselves registered. “However, a large number of seminaries are still operating without any registration, affiliation or specific identity,” he remarked.

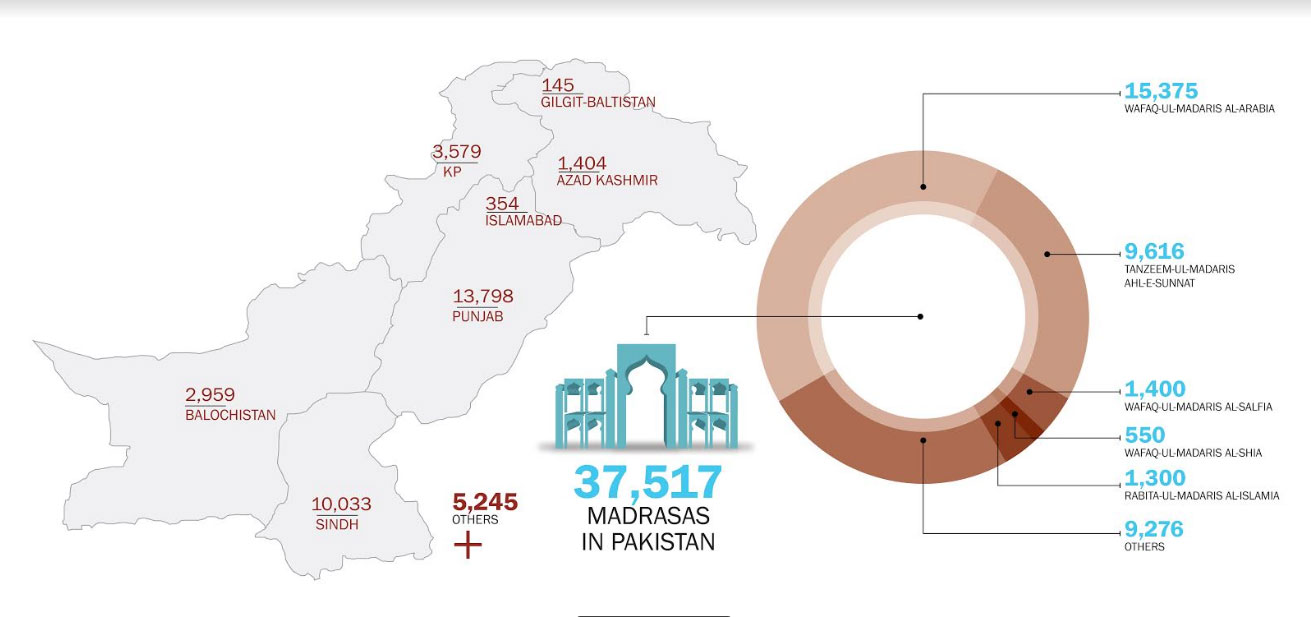

According to a study conducted by the Majlis-e-Ilmi Foundation Pakistan, a research centre based in Karachi, religious seminaries of various schools of thought have crossed the figure of 37,517 at present, in which around 4.59 million students are enrolled.

The data shows that 28,241 madrasas in the country are functioning under the umbrella of the five boards of the ITMP, whereas, 9,276 madrasas are functioning under other independent bodies, including Jamaat-ud-Dawa, Jamia Muhammadia Ghausia, Itihad-ul-Madaris, Wafaq Nizam-ul-Madaris, Al-Huda International, and others.

The foundation’s report of 2018 says 13,798 madarasas are running in Punjab, 10,033 in Sindh, 3,579 in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, 2,959 in Balochistan, 1,404 in Azad Jammu and Kashmir, 354 in Islamabad and 145 in Gilgit-Baltistan.

The plot repeats

As the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf came into power in the federal government after the 2018 general elections, it also stated its intention to regulate madrasas.

Recently on May 7, Federal Education Minister Shafqat Mahmood announced that all the religious seminaries would be working under the supervision of the education ministry and for this purpose, around 10 regional offices would be opened to register the madrasas while the unregistered seminaries would be shut down.

Possible course of action

“Even so, education has been devolved to provinces after 2010 as per the 18th Amendment. But it’s not a hurdle in regulating madrasas,” said Syed. He suggested that the “government should constitute a statutory body on the pattern of the Pakistan Bar Council for the accreditation and regulation of Islamic education.”

The journalist opined that religious learning should be considered as professional education because it is the need of our society. The role of mosques in our society could not be denied, he said, adding that the authorities have to put religious education in the right direction to prevent its further deterioration.

Dr Tuaseen was of the view that “graduates of Islamic learning centres have good command on Arabic. If the government provides vocational training and technical education to them, Pakistan would be able to produce a skilled workforce for Arab countries. But all such measures need implementation.”

Wifaqul Madaris Al-Arabia (WMAA) spokesperson Maulana Talha Rehmani told The News that The ITMP and its allies believed that modern education along with religious education would ultimately boost skills of the seminaries’ graduates. The madrasas have no issues in getting regularised, he maintained. “We are ready to cooperate with the federal ministry of education.”

However, Rehmani admitted that some of the issues such as the allocation of budget for the madrasas, appointments of teachers, limits of the government’s control on the seminaries, and others were yet to be addressed.

He said the ITMP’s biggest concern was the direct intervention of the government in the administrative affairs of the madrasas. The rest of the problems could be resolved in the future meetings, he added.

Under the NAP radar

In 2015, the federal government established the National Action Plan (NAP) based on 20 points to curb terrorism in the country. Under the plan, the federal interior ministry directed the provincial governments to formulate policies for letting madrasas into the mainstream educational system. The 10th point of the NAP was about “ensuring registration and regulation of religious seminaries”.

A 2019 study titled ‘National Action Plan: Achievements and Limitations’ authored by Najam Rafique states: “In order to regulate them, two separate [madrasas] data and [madrasas] registration forms have been developed by NACTA in consultation with ITMP. In Punjab and Sindh, the 100 per cent details of [madrasas] have been recorded whereas 80 per cent work has been done in KPK and Balochistan till December 2018.”

Some experts believe that only registration is not the solution to the problems and any effort to mainstream the madrasas that does not keep their financial model in view is bound to fail.

Wakil ur Rehman, a Karachi-based journalist covering religious parties, said “since 2002, the authorities have been trying to reform madrasas but they forget to diagnose the real issue.”

“A majority of madrasas run on charity funds that people donate for spiritual satisfaction. If the government wants to introduce formal education in seminaries, it will be its responsibility then to allocate grants for madrasas,” the journalist said.

He pointed out that under the Article 25-A of the Constitution of Pakistan, the state was supposed to provide free and compulsory education to all children between the ages of five and 16 years in such a manner as may be determined by the law. He asserted that without addressing the financial issues of madrasas, no attempt to bring reforms in them would meet success.

A possible way

In 2001, during the dictatorship of Gen Pervez Musharraf, the Pakistan Madrasah Education Board (PMEB) was introduced through an ordinance to regulate the madrasas and set up educational institutions that could provide both religious and formal education simultaneously.

The ordinance also aimed at inducting trained teachers at the seminaries, forming their academic councils, preparing the curriculum and devising an examination system along with other components that were needed for a complete formal education system.

Unfortunately, the PMEB's targets were never achieved as the board never became functional in a true sense. Only six meetings of the board were held from 2001 to 2004, followed by an 11-year gap. Until 2017, the board established only three seminaries in Islamabad, Karachi, and Sukkur during the 18 years after its establishment.

“The PMEB was a complete package for madrasa reforms,” Dr Tauseen said, lamenting that it did not work out because the stakeholders were not willing to implement it.

Regarding the curriculum development for the madrasas, he said, there were two best options available, one of which was using the curriculum of the Federal Board and the other was adopting the textbooks developed by the Allama Iqbal Open University, a public sector varsity that provides distance education. “It would also help eliminate differences among graduates studying at seminaries managed by different schools of thought,” he remarked.

Infographic by Faraz Maqbool

-

James Van Der Beek’s Family Faces Crisis After His Death

James Van Der Beek’s Family Faces Crisis After His Death -

Courteney Cox Celebrates Jennifer Aniston’s 57th Birthday With ‘Friends’ Throwback

Courteney Cox Celebrates Jennifer Aniston’s 57th Birthday With ‘Friends’ Throwback -

Camila Cabello Shares Update On Her Hair Two Years After Going Platinum

Camila Cabello Shares Update On Her Hair Two Years After Going Platinum -

Prince William Steps In To Help Farmer's Awareness Mission

Prince William Steps In To Help Farmer's Awareness Mission -

Queen Elizabeth Tied To Andrew's Sexual Abuse Case Settlement: Report

Queen Elizabeth Tied To Andrew's Sexual Abuse Case Settlement: Report -

Mark Ruffalo Urges Fans To Boycott Top AI Company Boycott

Mark Ruffalo Urges Fans To Boycott Top AI Company Boycott -

Prince William Joins Esports Battle In Saudi Arabia

Prince William Joins Esports Battle In Saudi Arabia -

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Are Being Ripped Apart: ‘Their Relationship Is Fully Fractured’

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Are Being Ripped Apart: ‘Their Relationship Is Fully Fractured’ -

Arden Cho Shares Update On Search For ‘perfect’ Wedding Dress Ahead Of Italy Ceremony

Arden Cho Shares Update On Search For ‘perfect’ Wedding Dress Ahead Of Italy Ceremony -

Ariana Madix Goes Unfiltered About Dating Life

Ariana Madix Goes Unfiltered About Dating Life -

Prince William Closes Saudi Arabia Visit With Rare Desert Shot

Prince William Closes Saudi Arabia Visit With Rare Desert Shot -

Priyanka Chopra Breaks Silence On Rumors Questioning Marriage To Nick Jonas

Priyanka Chopra Breaks Silence On Rumors Questioning Marriage To Nick Jonas -

'King Charles Acts Fast Or Face Existential Crisis' Over Andrew Scandal

'King Charles Acts Fast Or Face Existential Crisis' Over Andrew Scandal -

Brooklyn Beckham Charging Nearly £300 In Ticket Cost For Burger Festival

Brooklyn Beckham Charging Nearly £300 In Ticket Cost For Burger Festival -

Prince William Makes Unexpected Stop At Local Market In Saudi Arabia

Prince William Makes Unexpected Stop At Local Market In Saudi Arabia -

Zayn Malik Shares Important Update About His Love Life

Zayn Malik Shares Important Update About His Love Life