The new IMF programme

The country has reached a staff-level agreement with the IMF for a three-year programme. There were some last minute differences which were successfully ironed out by the two sides. This had led to a delay of couple of days in the announcement.

Pakistan has negotiated the programme from a position of weakness as it had fruitlessly delayed the programme since the government came to office in August last year. Before we reflect more on the current programme, it would be useful to reflect on how the delay has made things more challenging for the government.

Doing a programme at the outset of its term would have given the government a clean advantage that the economic mess it had inherited was not of its making and that it had come to office with a clear thinking and commitment for putting the economy back on track with the help of its development partners, most notably the IMF. Furthermore, the new government was also seen across the world as one that had come to power by defeating the two more powerful and internationally recognized political parties. Development partners were keen to resume business with the new political force headed by an international celebrity.

Contrary to the above line of thinking, the leaders of the new government found themselves shackled by their political rhetoric at the campaign trail against development partners and a misleading narrative against debt burden and debt-led development. An ambivalence towards development partners, therefore, was fashioned from the very beginning. Despite facing an acute balance of payments (BOP) crisis, the economic managers shunned any enthusiastic engagement with development partners. They were found inquiring from international financial institutions (IFIs) the rate of interest on their loans and telling them that they would compare it with private-sector lenders before making up their mind.

In an intriguing development, the government decided to seek temporary support from friendly countries (Saudi Arabia, UAE and China) and touted it as a substitute to approaching the IFIs. This support was quickly used up as the BOP and fiscal deficit remained elevated.

When the government presented its first mini-budget in late September, it made only peripheral changes to the budget originally presented by the outgoing government in May. The mini-budget was a clear signal that the government was not going to the IMF any time soon, for the budget adjustments were insufficient to alter the course of economic direction set in motion by the outgoing government. In another mini-budget in January, the government failed to make any adjustments; rather it ended up giving tax concessions to business and individuals.

While all this was going on, halfhearted efforts were made to secure a Fund programme. For the first time in the country’s history, a Fund programme mission returned without reaching an agreement. There was considerable diversion of views on the two sides. The breakdown, more than anything, reflected the continuing wariness toward an IMF programme and the discipline it would impose.

More surprisingly, the government made a number of conflicting policy moves. The applicable taxes on petroleum prices were frequently lowered either to reduce these prices or keep them constant. Interest rates were increased rapidly without realizing how costly it was for the budget. Exchange rate was adjusted sizeably which jolted the markets. Although a modest reprieve in the current account balance was achieved, the fiscal account was bleeding profusely: estimated at a staggering 7.6 percent of GDP. The revenue performance showed a growth of only two percent, worst in several decades. The drift in economic management finally culminated in slow growth, which dipped to 3.3 percent, lowest in five years, and rising poverty.

In this backdrop, when the moment came where the need for a new programme was felt, there was already an accumulation of imbalances that required immediate correction. A renewed effort was launched to reach an understanding with the Fund. There was also a realization that the economic team was unable to make the right decisions at critical junctures. During the middle of the negotiations with the IMF, wide-ranging changes were brought into the economic team by appointing a new minister (adviser), governor of the central bank and chairman of the revenue board.

It is difficult to recall another moment in the country’s history in the last three decades when it was so weakly placed in negotiating a Fund programme. Apart from weak fundamentals, our credibility was at the lowest level. Under the circumstances, conclusion of a programme is a welcome development as it would give relief to the markets which have been extremely nervous for many months.

The size of the programme at $6 billion is somewhat modest, sufficient to service the current level of outstanding IMF loans from the last programme. In a way, the programme amounts to effectively rescheduling the debt owed to the IMF for a longer maturity. Yet, it is still a significant support particularly as it opens the door for other lenders (World Bank and ADB) to provide policy loans. Furthermore, the programme would also help Pakistan access the international capital market where additional maturities are due in November.

Few details are available at this stage regarding the key elements of the programme. The announcement provides only the standard features typically contained in a Fund programme. It is for three years, entailing 12 quarterly reviews over a 39 months period. Fiscal adjustment, taxation, market based exchange rate, limiting government’s borrowings from the SBP, containing credit expansion would be the main elements of performance criteria. The structural policies would encompass SBP operational autonomy, settlement of arrears in the energy sector, cost recovery of energy services, FATF-related actions and focus on social spending. It is easier to get a programme but difficult to carry it through. The real test would be consistent performance under the programme till its conclusion.

The writer is a former finance secretary. Email: waqarmkn@gmail.com

-

Louvre Museum Director Resigns After $104m Crown Jewels Theft

Louvre Museum Director Resigns After $104m Crown Jewels Theft -

Sarah Ferguson 'crying' After Andrew Arrest

Sarah Ferguson 'crying' After Andrew Arrest -

Ghislaine Maxwell ‘late Night Massage’ Demands Exposed By Victim

Ghislaine Maxwell ‘late Night Massage’ Demands Exposed By Victim -

At Least 25 Dead, Hundreds Missing After Flash Floods, Landslides Strike Brazil

At Least 25 Dead, Hundreds Missing After Flash Floods, Landslides Strike Brazil -

King Charles' Office Breaks Silence After Prince Edward's Last-minute Withdrawal

King Charles' Office Breaks Silence After Prince Edward's Last-minute Withdrawal -

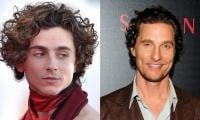

Timothee Chalamet Shares Major Learnings After Working With 'favourite' Director Christopher Nolan

Timothee Chalamet Shares Major Learnings After Working With 'favourite' Director Christopher Nolan -

Timothee Chalamet Heaps Praise For Matthew McConaughey's Work In Super Hit Project 'Interstellar'

Timothee Chalamet Heaps Praise For Matthew McConaughey's Work In Super Hit Project 'Interstellar' -

British MPs Pass A Motion Due To Andrew: ‘Lets Remove The Bandages From Our Mouths

British MPs Pass A Motion Due To Andrew: ‘Lets Remove The Bandages From Our Mouths -

Prince Edward Forced To Skip Royal Engagement With King Charles

Prince Edward Forced To Skip Royal Engagement With King Charles -

Sharon Osbourne Says Ozzy Osbourne 'knew' He Could Die Ahead Of Last Black Sabbath Show

Sharon Osbourne Says Ozzy Osbourne 'knew' He Could Die Ahead Of Last Black Sabbath Show -

Telegram Co-founder Pavel Durov Under Investigation: Russian State Media

Telegram Co-founder Pavel Durov Under Investigation: Russian State Media -

Ethan Hawke On Regrets He Had Related To Daughter Maya Hawke: 'Really, Really Hard'

Ethan Hawke On Regrets He Had Related To Daughter Maya Hawke: 'Really, Really Hard' -

Here's What 'Lizzie McGuire' Alum Jake Thomas Said About On Screen Dad Robert Carradine Ahead Of Death

Here's What 'Lizzie McGuire' Alum Jake Thomas Said About On Screen Dad Robert Carradine Ahead Of Death -

Nvidia Earnings Face AI Boom Test Amid Intensifying Market Competition

Nvidia Earnings Face AI Boom Test Amid Intensifying Market Competition -

UK Government Sign Off On Releasing Confidential Documents About Andrew: Here’s Why Now

UK Government Sign Off On Releasing Confidential Documents About Andrew: Here’s Why Now -

David Bowie's Daughter Alexandria Lexi Jones Recalls Painful Childhood Trauma: 'That Is Abuse'

David Bowie's Daughter Alexandria Lexi Jones Recalls Painful Childhood Trauma: 'That Is Abuse'