How sweet is CPEC?

We are such big-brother aficionados that in the 70 years since the country was first formed we have always had one looking over our shoulder. Even if it didn’t, we fooled ourselves in believing, it did. Tales of it are aplenty in our short history.

We are such big-brother aficionados that in the 70 years since the country was first formed we have always had one looking over our shoulder. Even if it didn’t, we fooled ourselves in believing, it did. Tales of it are aplenty in our short history.

When first offered to visit either Soviet Union or the US, we did the classic ‘eenie meenie miney mo’ and chose the US. It has taken all these years for Russia (formerly the Soviet Union) to come back to terms with us while it searches for some meat in this surprisingly resounding desire to accost Russia. Even this is based around that perpetual proclivity to have a big brother look over us as we play in our front-yard.

President Ayub Khan was the first to be dismayed, post the1965 war, with the US, which was unwilling to sacrifice India over us even as it enjoyed only peripheral relations with Nehru’s socialist-inclined India where affinity with the Soviet Union came naturally. It was at Pakistan’s peril to forget that India had entered into a war with China on American urging to teach Communist China a lesson. Not to forget that India had already had a brief fling with China in the 1950s when ‘Hindi-Cheeni Bhai-Bhai’ was a popular slogan. Ayub’s ‘Friends not Masters’ was an admission that the US, our hoped-for perpetual big-brother, had ditched us at a difficult time.

The signs of it must have come early. Ayub’s mercurial foreign minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, was not only young, and imbued with fresh idealism and a fiery vocabulary to go with it, he was also a handful as the country’s top diplomat. He had promised a 1000-year war with India on Kashmir, and had opened his country’s doors to China in 1964. This was the era of alliances – the mother of which were the cold-war antagonists, Nato and the Warsaw Pact.

The world, with only nominal exceptions, was neatly divided into the two camps. Smaller nations like Pakistan lent on a big power’s shoulder to assure their security while medium-sized nations like India sought eminence through association and for building their power potential. A competitive edge between the two leading communist states of the time meant that Russia and China had had their own little tiffs but Soviet Union was the more dominant. Hence when India lost to China in 1962, it went into Soviet arms for greater comfort.

America unreliable and India in the Soviet camp only meant that Pakistan would repose itself with China. China, having already vanquished India, was easily the more superior in this trichotomous engagement; it now carried the load of Pakistani aspirations. Despite its on-off spates of congeniality with the US over the following decades, Pakistan’s relationship with China has endured. Initially, China replaced the US as Pakistan’s support base for military equipment, and then as an economic partner when China’s own economic footprint grew. Today, politically, militarily and economically Pakistan is invested in retaining this association to ensure its sustenance along those facets. This has bound the two in a ‘dragon hug’.

In return, Pakistan served as China’s window to the world; this was when China was struggling to break from its communist stranglehold and economic straitjacketing. Today China is the fastest developing economy, only second in size to the US, and economically the most integrated country. If it is giving shivers to the US, that reflects its potency in continuing to prosper in all manifestations of economic, political and cultural influence, something the West has eternally sought. In dealing with it, Pakistan is faced with a new China which has moved beyond its Middle Kingdom epitaph to the domination of a globalised world through an integrated economy. If it also means in due course an opportunity for it to mutate into political influence over nations of interest that will only be natural to the scheme of things for great powers. Whichever way you form the argument, China is there for all to behold – regardless of which side of the divide one stands on.

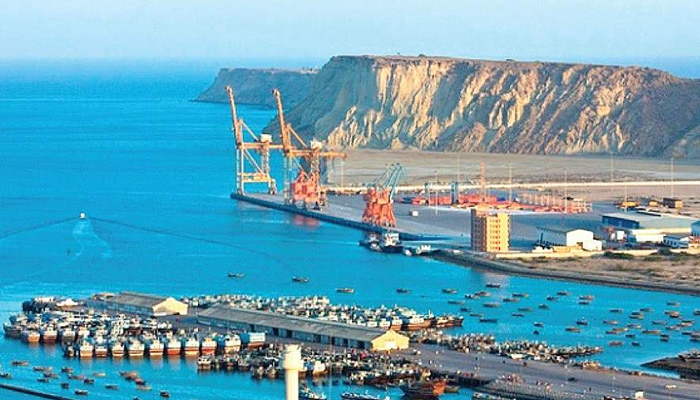

CPEC came along in the same spirit. This was the moment for China to seek permanent gains and it found a sterling opportunity in its grand Belt and Road Initiative to tie Pakistan in. CPEC will provide prosperity to China’s western regions and Pakistan was the avenue to that end. To a desperate Pakistan it was the lifeline it sought in an investment environment which had largely remained barren for it for years, imposing on it great economic pain.

Despite the lofty eulogies that characterised the relationship between the two countries, it was largely a negotiation between two patently unequal countries — one a patron, the other a perpetual dependent. To imagine that in agreeing to the terms and conditions Pakistan may have had a fair share of its interests served is fallacious, regardless of how high the Himalayas sit or how deep be the oceans that China’s western regions will connect with. Of honey from the Uyghur Autonomous Region, one can say little.

Make no mistake. Pakistan’s lot has been cast, nice and proper, with China since decades and for the foreseeable decades, such is the nature of this dependence relegated from former interdependence. It is fortuitous enough for Pakistan that it still persists as a friend when China is on a rapid ascent, soon to be the world’s most dominant economic power. After having been invested in this relationship for decades, now is the time for it to hold on to the promise that this association carries and benefit from what it will deliver. Yes, there is a cost and it is reflected in the various memes which get depicted on social media of how China’s is now a parallel culture in Pakistan, but that may be a small price to pay for the longer-term benefit of climbing out of the hole that the Pakistani economy finds itself in.

The smarter thing was always to weave in what was important to Pakistan while we worked with the Chinese on CPEC. Much gushed by the immediacy that came with such substantial investment on a spur, we probably agreed to everything that China desired lest we lose the opportunity. Some of the things that we may like to review (even if they have already been finalised) include: accepting the relocation of the coal/furnace based power-plants that China was retiring at an environmental cost, their idle-time compensation and commitments of minimum returns favourable to Chinese companies; tenures of loans and the terms of repayment; opportunity for Pakistani industry as well as induction of technology relevant to the future needs of Pakistan; and creation of jobs for Pakistanis in the main.

Given the intensity of this relationship, there should be enough space to review – to the satisfaction of the new administration in Pakistan – and allow what may be of significant benefit to Pakistan without compromising on China’s aims of undertaking the project with such a huge investment. CPEC must stay, it is essential to Pakistan’s immediate needs and can be crucial to determining the country’s future if soundly partnered. There should be enough honey in there to subsume any bitterness.

Email: shhzdchdhry@yahoo.com

-

Record Set Straight On King Charles’ Reason For Financially Supporting Andrew And Not Harry

Record Set Straight On King Charles’ Reason For Financially Supporting Andrew And Not Harry -

Michael Douglas Breaks Silence On Jack Nicholson's Constant Teasing

Michael Douglas Breaks Silence On Jack Nicholson's Constant Teasing -

How Prince Edward Was ‘bullied’ By Brother Andrew Mountbatten Windsor

How Prince Edward Was ‘bullied’ By Brother Andrew Mountbatten Windsor -

'Kryptonite' Singer Brad Arnold Loses Battle With Cancer

'Kryptonite' Singer Brad Arnold Loses Battle With Cancer -

Gabourey Sidibe Gets Candid About Balancing Motherhood And Career

Gabourey Sidibe Gets Candid About Balancing Motherhood And Career -

Katherine Schwarzenegger Shares Sweet Detail From Early Romance Days With Chris Pratt

Katherine Schwarzenegger Shares Sweet Detail From Early Romance Days With Chris Pratt -

Jennifer Hudson Gets Candid About Kelly Clarkson Calling It Day From Her Show

Jennifer Hudson Gets Candid About Kelly Clarkson Calling It Day From Her Show -

Princess Diana, Sarah Ferguson Intense Rivalry Laid Bare

Princess Diana, Sarah Ferguson Intense Rivalry Laid Bare -

Shamed Andrew Was With Jeffrey Epstein Night Of Virginia Giuffre Assault

Shamed Andrew Was With Jeffrey Epstein Night Of Virginia Giuffre Assault -

Shamed Andrew’s Finances Predicted As King ‘will Not Leave Him Alone’

Shamed Andrew’s Finances Predicted As King ‘will Not Leave Him Alone’ -

Expert Reveals Sarah Ferguson’s Tendencies After Reckless Behavior Over Eugenie ‘comes Home To Roost’

Expert Reveals Sarah Ferguson’s Tendencies After Reckless Behavior Over Eugenie ‘comes Home To Roost’ -

Bad Bunny Faces Major Rumour About Personal Life Ahead Of Super Bowl Performance

Bad Bunny Faces Major Rumour About Personal Life Ahead Of Super Bowl Performance -

Sarah Ferguson’s Links To Jeffrey Epstein Get More Entangled As Expert Talks Of A Testimony Call

Sarah Ferguson’s Links To Jeffrey Epstein Get More Entangled As Expert Talks Of A Testimony Call -

France Opens Probe Against Former Minister Lang After Epstein File Dump

France Opens Probe Against Former Minister Lang After Epstein File Dump -

Last Part Of Lil Jon Statement On Son's Death Melts Hearts, Police Suggest Mental Health Issues

Last Part Of Lil Jon Statement On Son's Death Melts Hearts, Police Suggest Mental Health Issues -

Leonardo DiCaprio's Girlfriend Vittoria Ceretti Given 'greatest Honor Of Her Life'

Leonardo DiCaprio's Girlfriend Vittoria Ceretti Given 'greatest Honor Of Her Life'