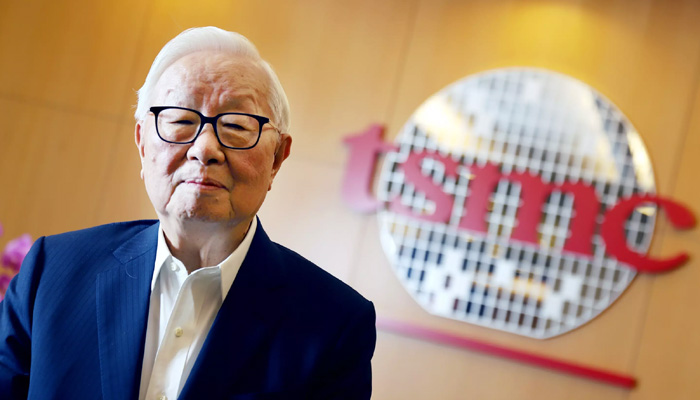

How the tech tycoon you’ve never heard of changed the world

Morris Chang rarely gets a mention alongside the world’s best-known technology entrepreneurs, such as Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos. Few outside the tech industry know of him. But Chang has arguably had as big an effect on the world of technology, and our daily lives, as any of those household names. His company, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), helped usher in the microchip revolution that the present day personal electronics boom has been built on.

By the time Chang stepped down as CEO last week, at the age of 87 and after leading the company for 31 years, he had turned TSMC into the world’s largest chip manufacturer, a £150bn behemoth that supplies Apple and Qualcomm. Without his influence, the tech industry – and the world – would be very different today.

Chang left civil war-gripped China in 1948 for America, where he worked at Texas Instruments, then an up-and-coming semiconductor manufacturer. It was not until he was in his 50s – a dinosaur by tech industry standards – that he set up TSMC in Hsinchu in northern Taiwan, with the backing of the country’s government.

The electronics industry was much smaller back then. Mobile phones had barely begun to take off, and were the size of bricks. Personal computers were in few homes and offices.

Microchips are the building blocks of personal electronics, and devices that cost a few pounds have several of them nowadays, but the plants in which they are made, known as “fabs”, are prohibitively expensive to build and maintain. In the Eighties, it wasn’t enough to have the technical ability to design chips, a company also needed enormous resources to make them.

The expense of manufacturing microchips on an industrial scale meant the industry was in the hands of a few companies, such as Intel, Texas Instruments and a handful of Japanese manufacturers such as Fujitsu.

These “integrated” manufacturers both designed and built the chips that ended up in computers and mainframes. TSMC changed this, starting off as a “foundry” that existed merely to produce chips designed by others.

Chang was ridiculed when he set up the company, but knew he was taking advantage of one of Taiwan’s few technological strengths, in manufacturing, and that eventually the demand would come.

His breakthrough came just at the right time. TSMC’s fab allowed a string of smaller manufacturers to specialise in developing semiconductor-related intellectual property, without these enormous fixed costs. What followed were the present day titans of the industry, such as American leaders Qualcomm and Nvidia, and Britain’s Arm.

The pattern was similar to the software developer revolution that has been enabled by services such as Windows, the World Wide Web, and cloud computing businesses such as Amazon Web Services. Just as these “platforms” allowed developers to build new services on top of them, without having to worry about the underlying architecture, Chang’s company reduced the barriers to entry for semiconductor companies.

This allowed new, specialised types of microchips to be built such as the graphics units that are required for advanced video processing. And as hand-held electronics, PCs and more advanced mobile phones began to take off, microchip sales subsequently boomed.

In 1987, when TSMC was set up, the global semiconductor industry registered $33bn (£25bn) in sales. Last year, they passed $400bn. Revenues of “fabless” semiconductor companies that rely on companies such as TSMC surpassed $100bn for the first time.

Growth has picked up as microchips become embedded in a wider variety of devices from washing machines to cars, and amid growing demand for specially-designed ones dedicated to artificial intelligence or cryptocurrency mining.

These days the company manufacturers the processing unit at the centre of the iPhone and is a vital partner for Apple, which in turn is its biggest customer.

It is still going strong, at more than five times the size of its biggest competitor, China’s GlobalFoundries, when measured by sales. Its lead allows levels of investment that make it increasingly unassailable: as the transistors that microchips are built of have been shrunk to impossible proportions, each year requires ever increasing amounts of investment to produce the advances in processing power that we have become accustomed to over recent decades.

Last year also saw another milestone, when TSMC’s market capitalisation briefly passed that of Intel, the US giant that has for so long been the first name in the microchip industry.

Chang hardly needed the validation, but one suspects he may have enjoyed the moment. As he departed TSMC at its annual meeting last week, Chang looked back at his career by boasting that “if we were not around, billions of people around the world would live differently than they do now”.

Even if few people know his name, Morris Chang deserves his place in the pantheon of tech greats.

-

Prince William Questions Himself ‘what’s The Point’ After Saudi Trip

Prince William Questions Himself ‘what’s The Point’ After Saudi Trip -

James Van Der Beek's Friends Helped Fund Ranch Purchase Before His Death At 48

James Van Der Beek's Friends Helped Fund Ranch Purchase Before His Death At 48 -

King Charles ‘very Much’ Wants Andrew To Testify At US Congress

King Charles ‘very Much’ Wants Andrew To Testify At US Congress -

Rosie O’Donnell Secretly Returned To US To Test Safety

Rosie O’Donnell Secretly Returned To US To Test Safety -

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Spotted On Date Night On Valentine’s Day

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Spotted On Date Night On Valentine’s Day -

King Charles Butler Spills Valentine’s Day Dinner Blunders

King Charles Butler Spills Valentine’s Day Dinner Blunders -

Brooklyn Beckham Hits Back At Gordon Ramsay With Subtle Move Over Remark On His Personal Life

Brooklyn Beckham Hits Back At Gordon Ramsay With Subtle Move Over Remark On His Personal Life -

Meghan Markle Showcases Princess Lilibet Face On Valentine’s Day

Meghan Markle Showcases Princess Lilibet Face On Valentine’s Day -

Harry Styles Opens Up About Isolation After One Direction Split

Harry Styles Opens Up About Isolation After One Direction Split -

Shamed Andrew Was ‘face To Face’ With Epstein Files, Mocked For Lying

Shamed Andrew Was ‘face To Face’ With Epstein Files, Mocked For Lying -

Kanye West Projected To Explode Music Charts With 'Bully' After He Apologized Over Antisemitism

Kanye West Projected To Explode Music Charts With 'Bully' After He Apologized Over Antisemitism -

Leighton Meester Reflects On How Valentine’s Day Feels Like Now

Leighton Meester Reflects On How Valentine’s Day Feels Like Now -

Sarah Ferguson ‘won’t Let Go Without A Fight’ After Royal Exile

Sarah Ferguson ‘won’t Let Go Without A Fight’ After Royal Exile -

Adam Sandler Makes Brutal Confession: 'I Do Not Love Comedy First'

Adam Sandler Makes Brutal Confession: 'I Do Not Love Comedy First' -

'Harry Potter' Star Rupert Grint Shares Where He Stands Politically

'Harry Potter' Star Rupert Grint Shares Where He Stands Politically -

Drama Outside Nancy Guthrie's Home Unfolds Described As 'circus'

Drama Outside Nancy Guthrie's Home Unfolds Described As 'circus'