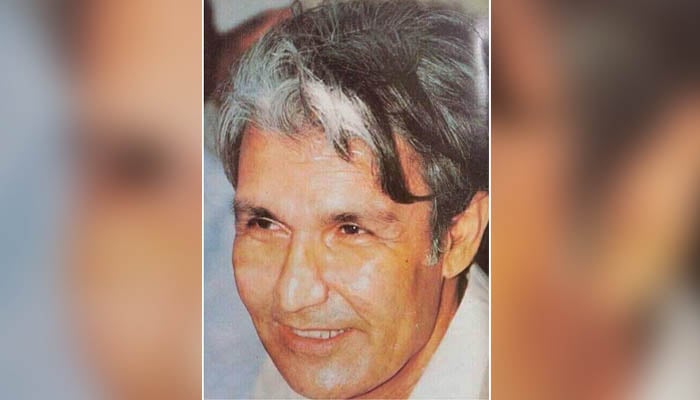

Palijo’s legacy

The demise of Rasool Bux Palijo – a stalwart politician and intellectual from Sindh, and one of the greatest writers of Sindhi prose in the 20th century – has not only left thousands of his workers orphaned but has also dealt a blow to the politics of ideology and commitment, and the path to salvation.

Rasool Bux Palijo’s narrative for Sindh was entirely different from what his contemporaries in the business of politics had proposed. He remained a strong proponent of Sindh’s rights. In his own creative and scientific way, he proved to be a brilliant advocate of the province’s rights. Palijo’s approach to politics and society was influenced by Marxist literature and leftist movements in third world countries during the post World War-II era.

But the traditional Marxist activists and nationalists of his era refused to see him as one of their own because he didn’t consider ideological influences to be dogmatic. Palijo was neither a Marxist in the way that the Communist Party of Pakistan would adhere to the rigid ideological lines of the Marxist theory, nor a nationalist like G M Syed, who sought clear-cut national unity and ignored class divisions and exploitation in society.

Palijo hailed from Sindh’s peasantry and read widely about the history of revolutionary movements in post-colonial societies such as Vietnam, China, Angola and Mozambique. It took him years to develop his own ideological framework and thesis on which to base his politics on. In his book, ‘Subuh thendo’ (‘Dawn will come’), he presented the exploitation of Sindh’s people along national and class lines and coined a suitable way forward: the Qaumi Awami Jamhoori Inqilab’ (the National People’s Democratic Revolution). ‘Subuh Thendo’ is categorised as a form of original political literature. It offers a critique on how Pakistan’s undemocratic regimes developed a nexus of vested interests to further their agenda to deprive people of their rights on three fronts: democratic, class and national questions.

It took decades for him to get his workers and activists in Sindh to truly grasp the ideological foundations he had built. This is why he was unique and inspiring. It was the power of his ideas that helped him build a strong political base across Sindh. Palijo was the first political leader who hailed from a lower middle class family in rural Sindh to lay the foundation for a Marxist party with distinctly Sindh-based characteristics.

The revolutionary poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai was a recurring theme in his politics. The titles of most of Palijo’s books were derived from Bhitai’s poetic lines and expressions. Even his political activism and mobilisation was built around Shah Latif’s poetry. No one celebrated Bhitai’s urs in Sindh like he did. Through Bhitai’s poetry, Palijo would explain his political ideas and future direction. As a result, his words would come across as songs of liberation to the ears of his followers.

Palijo’s rise to politics occurred at a time when Sindh and Pakistan were thrilled with the launch of two key political parties. ZAB had launched the PPP at the federal level and G M Syed had started the Jeay Sindh Tehreek (JST) in Sindh in the late 1960s and the early 1970s. Along with a group of intellectuals and writers, such as poet Shaikh Ayaz and Hafeez Qureshi, Palijo launched the Sindhi Awami Tehreek. Agha Saleem, one of his contemporaries, called him a “great farsighted agitator”.

His famous treatises on literature and politics already existed in politico-literary circles. A lawyer by profession, writer by compulsion and a politician by passion, Palijo was like a rising sun on the political spectrum back in the 1970s. The rise of Bhutto’s political power could not weaken his resolve. Palijo preached and practised the art of swimming against the tide. He gathered the necessary elements to align women, students, children, writers and intellectuals to attack the exploitative structures within the federal polity and various social structures.

Although Palijo had started his political activism with the Sindh Hari Committee of comrade Hyder Bux Jatoi and, later, the National Awami Party (NAP), he chose to embark on his own direction. In the 1960s, he was imprisoned along with his family members, including women. His wife – the iconic Sindhi musician and singer Jiji Zarina Baloch, who sang songs about liberation, unity, history and the masses – stood by him in the long struggle that eventually kept him away from her.

Palijo lived an extraordinary life. But there was nothing normal about his life. He didn’t get the opportunity to raise his children – a task his wives performed singlehandedly. He would only get to see his children when they came to visit him in jail or during court hearings.

Successive military regimes kept him imprisoned for 11 years. Palijo’s imprisonment could not silence his workers. He issued directives from jail and wrote analyses on the changes that the world was witnessing – including those that predicted the collapse of the Soviet Union. During this time at the infamous Kot Lakhpat jail, he wrote a book that became a masterpiece in Sindhi literature. His jail diary was published as ‘Kot Lakhpat jo Qaidi’ (Prisoner of Kot Lakhpat).

Rasool Bux Palijo empowered Sindhi peasant women by giving them a power political platform: the Sindhiyani Tehreek. This platform has, to date, remained active and popular. Palijo did not see the collapse of the Soviet Union as the end of Marxism. He also rejected Professor Samuel Huntington’s flawed thesis on the Clash of Civilisations. Palijo remained pro-China and followed a reformist agenda.

Palijo’s lifelong political struggle is a legacy of resistance and awakening that combined literature and scientific consciousness. He not only dreamt of a better world, but also believed in working towards it without succumbing to the lure of power politics.

Did he achieve his goals? Was he a successful politician? Did he usher in the revolution that he sought for decades? He firmly believed that the journey to achieve liberation was worth undertaking. Palijo has left an indelible imprint on the lives of many people who came across to him. His 26 books and the well-compiled audio and video archives of his speeches will remain with us as a reminder of the meaningful life that he lived. With his death, we have lost one of its most powerful, intelligent and sincere advocates of Sindh’s rights.

Email: mush.rajpar@gmail.com

Twitter: @mushrajpar

-

UK Asylum System Faces Changes As Refugees Will Get Temporary Protection Only

UK Asylum System Faces Changes As Refugees Will Get Temporary Protection Only -

Meghan Markle Has Realised ‘star Power’ Is Not Enough After Jordan Trip

Meghan Markle Has Realised ‘star Power’ Is Not Enough After Jordan Trip -

USC Leading Scorer Chad Baker-Mazara Leaves Program Amid Losing Streak

USC Leading Scorer Chad Baker-Mazara Leaves Program Amid Losing Streak -

Google Is Winding Down Popular App 'Pixel Studio': Here's Why

Google Is Winding Down Popular App 'Pixel Studio': Here's Why -

Zendaya, Tom Holland Secretly Married?

Zendaya, Tom Holland Secretly Married? -

Dove Cameron Reveals Why She's Limiting Relationship Talk After Damiano David Engagement

Dove Cameron Reveals Why She's Limiting Relationship Talk After Damiano David Engagement -

Bulls Vs Bucks: Giannis Out, Simons And Williams Sidelined

Bulls Vs Bucks: Giannis Out, Simons And Williams Sidelined -

Princess Beatrice Is ‘haunted’ By Dreadful Shamed Andrew Arrest

Princess Beatrice Is ‘haunted’ By Dreadful Shamed Andrew Arrest -

Panthers Vs Islanders: Dmitry Kulikov Returns From Injured Reserve As Schwindt Hits IR

Panthers Vs Islanders: Dmitry Kulikov Returns From Injured Reserve As Schwindt Hits IR -

SAG-AFTRA Drops SAG Awards Name To Rebrand

SAG-AFTRA Drops SAG Awards Name To Rebrand -

Next Full Moon: How To Watch The Total Lunar Eclipse On March 3

Next Full Moon: How To Watch The Total Lunar Eclipse On March 3 -

Bhad Bhabie Shares Tender Moment With Daughter Amid Cancer Setback Hint

Bhad Bhabie Shares Tender Moment With Daughter Amid Cancer Setback Hint -

Silver, Gold Prices Surge Amid Geopolitical Uncertainty After US-Israel Attack On Iran

Silver, Gold Prices Surge Amid Geopolitical Uncertainty After US-Israel Attack On Iran -

Britain To Trial Social Media Ban For Hundreds Of Thousands Of Children Under-16

Britain To Trial Social Media Ban For Hundreds Of Thousands Of Children Under-16 -

Prince Harry Should Face Same Fate As Shamed Andrew, Says Expert

Prince Harry Should Face Same Fate As Shamed Andrew, Says Expert -

Oil Price Jumps, Stocks Fall After US And Israel Strike Iran

Oil Price Jumps, Stocks Fall After US And Israel Strike Iran