Who should lead a debate on BISP?

Between 1999 and 2005, General Musharraf had sanctified a dramatic expansion of the responsibilities of the officer corps of the army. As Waziristan was coming under the control of what LTG Shuja Pasha once called the United Nations of terrorists, soldiers and officers were busy trying to fix Wapda (LTG Zulfiqar Ali Khan), running the federal education ministry (LTG Javed Ashraf Qazi), negotiating higher taxes with small and medium sized shopkeepers (LTG Moinuddin Haider), and trying to win the cricket world cup (LTG Tauqeer Zia).

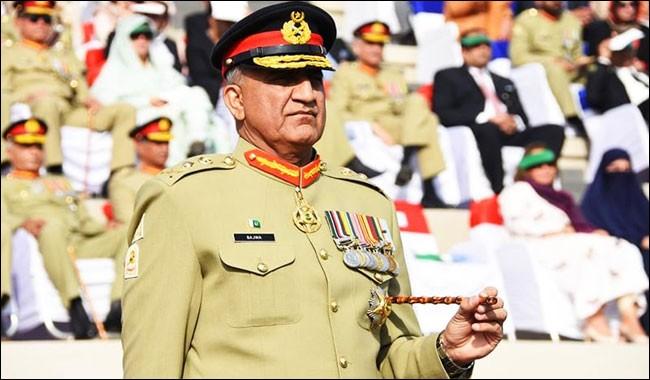

We know how that movie ended. Pakistan needed six years of General Kayani to purge the army’s knack to do things it is not trained to do. The country spent a decade pinballing from one terrorist attack to another. No responsible state or society should ever forget attacks like the one at PNS Mehran, GHQ, the ISI office in Faisalabad and the Special Operations Task Force at Tarbela. Our soldiers and officers – Pakistan’s bravest sons and daughters – have given so much in blood, in limbs and in lives that the memory of what the Zia and Musharraf eras did to Pakistan should never, ever be allowed to fade. The unfolding narratives in the run up to the 2018 elections run the risk of causing this memory to fade, with a “Bajwa doctrine” comprising the military’s take on a wide array of civilian matters having been kicked into high gear, and with the corps of officers being dragged into domains which they have neither the expertise, nor experience, nor legal authority to publicly take positions on.

Does the military have a legitimate interest in how democracy functions? Absolutely. Does the military have a stake in the manner in which federalism is interpreted by the executive, by parliament and by the judiciary? Of course it does. Should the military be concerned with issues like poverty, fissiparous political threads and national harmony? Those are all areas that the military establishment will have a view on.

But having a perspective is not the same thing as a proactive effort to engage in public debate on these issues. There are formal (National Security Council) and informal (social and official interactions with the prime minister and his cabinet) mechanisms through which the military’s perspective is supposed to be absorbed into the central nervous system of the state. In practice, it seems rather facile to make this assertion. But it begs repetition when the military’s tendency to shape public perception grows from helping mobilise clarity on the terrorist threat, to helping mobilise opposition to the 18th Amendment to now, of all things, the articulation of an aversion to the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP). It begs the question as to how a social protection instrument has ended up getting into the crosshairs of an election year ramping up of the army’s political interventions.

At a time when all around the world, the twin anvil of demographic and technological anxiety is generating debates about instruments that guarantee a baseline quality of life, Pakistan’s hard-won BISP seems to have become a target of a wider assault on civilian symbols. This is exactly like the kind of clumsy public policy posturing that characterised the Musharraf era – a mass of well-intentioned men and women belonging to the military establishment engaging in topics that they know very little about.

The first thing to understand about BISP is that it is essentially an intervention of the last resort. It is not meant to offer a living wage to its recipients, but instead a small boost to household income to help keep families on the precipice of extreme poverty from plunging into dire straits. Its seeds were originally planted, ironically, during the Musharraf era as economists, donors and bureaucrats attempted to conceive of a quick and effective frontline weapon against extreme vulnerability to economic shocks. The existing social protection tools at the time such as the Baitul Maal and the Zakat Funds were seen as being too politically sensitive to be reformed. Back then, the brand name ‘Khushal Pakistan’ was being used for a basket of ideas for a programme, and many of the ideas for its deployment were derivatives of lessons from the cash grants made for housing in the aftermath of the 2005 earthquake.

The eventual shape of the BISP programme, and especially its unique targeting of women and women-led households, was the imprint of the first wave of public policy energy that the newly elected PPP-led coalition government brought to Islamabad in 2008, notably economist Kaiser Bengali. Since then, BISP has evolved significantly in two iterations. In the first, which took place during the PPP government prior to 2013, BISP’s means-testing mechanism was honed so that both government officials and international organisations like the World Bank developed a growing confidence in the selection process for BISP cash grants – ensuring that recipients genuinely merited the small, but important boost that this cash offered to women and women-led households.

In the second iteration, which was piloted between 2012 and 2015, and deployed to scale in various domains thereafter, under Marvi Memon’s leadership, BISP began to distribute cash transfers conditioned on very specific terms, with very specific targets. One very important example of such transfers is the Waseela-e-Taleem programme that awards top-ups on regular BISP payments against evidence of new enrolments of a family’s children in school, and a minimum 80 percent attendance record at school. To date, two million children have been recorded as having enrolled through this intervention. In fairness, those numbers have likely been spurred by growing investments in government schools since 2013 across all four provinces, especially Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – but the programme represents exemplary public policy from an anti-poverty standpoint.

Is BISP so perfect that it cannot be criticised or improved? Of course not. But the foundation for such a discussion needs to be hinged on a comprehensive understanding of poverty and poverty reduction. Faisal Bari wrote the original working paper to help consolidate thinking about social protection instruments in Pakistan in 2006. Kaiser Bengali helped shape BISP in its initial days. Haris Gazdar has studied nutrition extensively. Sania Nishtar has important health insights that can inform BISP’s potential as a vehicle for improved health. Zeba Sathar is the country’s finest demographer. These are the kinds of people that have the authority to speak about BISP – and both criticise it and suggest improvements to it.

We are less than four months from a general election; and Pakistan needs informed debate about how to save the poor from becoming extremely poor. We need debate about the fourth industrial revolution and its impact on jobs – and whether the coming era necessitates instruments like universal basic incomes or stakeholder grants. We need to think more carefully about suggestions like the ones made in Nadeem ul Haque’s book, ‘Looking back: How Pakistan became an Asian Tiger by 2050’ in which he proposes a flat 60 percent tax on inheritances above 500 million rupees. These kinds of ideas about raising money for the state are as critical as ideas about how to spend money.

Pakistan needs to have all of these debates. And none of these debates requires the opinion of the army chief to start or settle them. Pakistan’s soldiers and spies have worked too hard and sacrificed too much to be dragged back into domains that are not theirs. Long live the Pakistan Army, long live the state’s ability to help the poor, and long live Pakistan.

The writer is an analyst and commentator.

-

Factory Explosion In North China Leaves Eight Dead

Factory Explosion In North China Leaves Eight Dead -

Blac Chyna Opens Up About Her Kids: ‘Disturb Their Inner Child'

Blac Chyna Opens Up About Her Kids: ‘Disturb Their Inner Child' -

Winter Olympics 2026: Milan Protestors Rally Against The Games As Environmentally, Economically ‘unsustainable’

Winter Olympics 2026: Milan Protestors Rally Against The Games As Environmentally, Economically ‘unsustainable’ -

How Long Is The Super Bowl? Average Game Time And Halftime Show Explained

How Long Is The Super Bowl? Average Game Time And Halftime Show Explained -

Natasha Bure Makes Stunning Confession About Her Marriage To Bradley Steven Perry

Natasha Bure Makes Stunning Confession About Her Marriage To Bradley Steven Perry -

ChatGPT Caricature Prompts Are Going Viral. Here’s List You Must Try

ChatGPT Caricature Prompts Are Going Viral. Here’s List You Must Try -

James Pearce Jr. Arrested In Florida After Alleged Domestic Dispute, Falcons Respond

James Pearce Jr. Arrested In Florida After Alleged Domestic Dispute, Falcons Respond -

Cavaliers Vs Kings: James Harden Shines Late In Cleveland Debut Win

Cavaliers Vs Kings: James Harden Shines Late In Cleveland Debut Win -

2026 Winter Olympics Snowboarding: Su Yiming Wins Bronze And Completes Medal Set

2026 Winter Olympics Snowboarding: Su Yiming Wins Bronze And Completes Medal Set -

Trump Hosts Honduran President Nasry Asfura At Mar-a-Lago To Discuss Trade, Security

Trump Hosts Honduran President Nasry Asfura At Mar-a-Lago To Discuss Trade, Security -

Cuba-Canada Travel Advisory Raises Concerns As Visitor Numbers Decline

Cuba-Canada Travel Advisory Raises Concerns As Visitor Numbers Decline -

Anthropic Buys 'Super Bowl' Ads To Slam OpenAI’s ChatGPT Ad Strategy

Anthropic Buys 'Super Bowl' Ads To Slam OpenAI’s ChatGPT Ad Strategy -

Prevent Cancer With These Simple Lifestyle Changes

Prevent Cancer With These Simple Lifestyle Changes -

Air Canada Flight Diverted St John's With 368 Passengers After Onboard Incident

Air Canada Flight Diverted St John's With 368 Passengers After Onboard Incident -

Experts Reveal Keto Diet As Key To Treating Depression

Experts Reveal Keto Diet As Key To Treating Depression -

Inter Miami Vs Barcelona SC Recap As Messi Shines With Goal And Assist

Inter Miami Vs Barcelona SC Recap As Messi Shines With Goal And Assist