Reign of discretion: Part - II

Our chief justice has complained that the Supreme Court has been consumed by cases of a political nature, eating up time that ought to be committed to disputes involving ordinary Joes. It is unclear why the SC would define and exercise its discretionary jurisdiction such that it gets entangled in the political thicket and is unable to devote due attention with required dispatch to cases of lesser citizens that have been pending for decades.

Is the pendulum swinging back towards an Iftikhar Chaudhry-style of judicial populism wherein street campaigns and media trials are triggers for court proceedings and not extraneous considerations?

The SC’s maintainability reasoning in the Imran Khan disqualification case is astounding: “It is crucial at this stage to emphasise that we have expended time and efforts in our original jurisdiction for the sake of public interest in the circumstances of the public outcry against corruption that arose as a result of the Panama Papers’ leak. Otherwise, the appropriate form in a case of such nature, calling for the disqualification of an elected legislator, is either the Election Tribunal or where there are established or admitted facts indicating disqualification, then before the learned high courts of the country in their constitutional jurisdiction.”

Has the SC just ruled that populism will be part of the formal test for assumption of 184(3) jurisdiction? Will political campaigns and coverage by media determine whether the SC will consider a matter to be one of public importance? While refusing to probe the allegation that the PTI received foreign funding, the SC held that, “it would be appropriate for this court not to exercise its jurisdiction under Article 184(3) of the constitution so as to avoid interfering with the power and jurisdiction specifically conferred by the PPO upon special fora ie the

federal government and the ECP respectively.”

If this is how the SC interpreted Article 17 read together with the Political Parties Order and exercised restraint, why did the same approach not apply while reading Articles 62/63 together with 225 and Representation of Peoples Act? Why did the SC not exercise the same restraint in Jehangir Tareen’s case to hold that the SC ought not interfere with jurisdiction vested in the ECP and the speaker? Further, if it is settled law that cases ought to be instituted at the lowest available forum, why did the SC not order that quo warranto proceedings be instituted at high courts to not deprive litigants of their right to appeal before the SC?

The SC’s reasoning in the IK case is in contrast to that in the JKT case. JKT has been disqualified for non-disclosure of his beneficial interest under a trust that holds the offshore company, which in turn holds a UK property. While recognising that the property was purchased by tax paid money sent abroad by JKT through banking channels, it found JKT dishonest for non-disclosure, after rejecting his assertion that he had gifted the asset to his children (who disclosed it in their wealth statements). Here the SC’s focus is on beneficial ownership, its approach is inquisitorial and it willingly peeps behind corporate veils to do complete justice.

In IK’s case, on the contrary, the SC focuses exclusively on legal interest as opposed to beneficial. While giving IK a clean chit of health, the SC holds that, “we do not find that failure by [the] respondent to mention a trust vehicle company as his asset in which he neither held any shares not any office in the management, can tantamount to misdeclaration or concealment constituting an act of dishonesty. This is especially so when we are not convinced of any benefit, financial or otherwise that was or could be derived by the respondent on account of such non-disclosure.” What benefit did JKT derive from non-disclosure?

The test employed in JKT’s case vests hard discretion (in Dworkinian terms) in the SC such that different judges could draw different conclusions from identical facts. Consider IK’s case: the SC observes in para 59 that, “even if foreign earnings as non-resident were the source of funding for the London flat, yet it was an asset which he was bound to disclose in his wealth tax return under the Wealth Tax Act, 1963 after he became a filer in 1981. Therefore, the respondent was a defaulter in relation to his duty under the Wealth Tax Act, 1963. This situation continued until 1.3.2000…”

But while dismissing the plea that IK concealed the London flat while filing nominations papers in Election 1997, the SC observes that, “this plea is not contained in [petitioner’s] pleadings nor did he produce any evidence in support thereof…the petitioner was merely speculating without certainty and with conjecture. The document in issue is twenty years old which the ECP statedly no longer had in its record. The nomination paper had been accepted without objection but the respondent had lost the election. The matter was a past and closed transaction…”

Thus, after having declared itself that the London flat was never disclosed except under the Amnesty Scheme of 2000, the SC does three things here: one, it gives IK benefit of the doubt and assumes that he might have disclosed the flat in his nomination papers in 1997 (while not having done so in his wealth statement till after 1999); two, refuses to go inquisitorial; and three, puts onus of proof on the petitioner and holds that the onus hasn’t been discharged, instead of putting to use Article 122 of the Qanun-e-Shahadat Order and requiring IK

to clarify facts that are especially within his knowledge (as it does in JKT’s case).

While concluding that the only asset IK’s offshore company held was the London flat and there was nothing to disclose once the flat was sold, the SC also states that Niazi Services Limited (NSL) was kept alive for receipt of rent payable under a court decree. So there was an amount of GBP42,000 in overdue rent receivables recovered by NSL between 2006 and 2010 on IK’s behalf and not declared anywhere. This non-declaration finds no mention in the SC’s analysis. However, it is on the basis of such trivial non-disclosures (as opposed to proven corruption charges) that the SC disqualified a PM and the PTI’s secretary general after declaring them dishonest.

The point here isn’t that the SC should have disqualified IK. It shouldn’t have. But it shouldn’t also have disqualified JKT (or NS for that matter) and labelled them dishonest on the basis of a tentative view formed without trial under 184(3). From an institutional perspective, the SC has expanded its jurisdiction at the expense of the ECP, the offices of the speaker and the chairman Senate and the high courts. This new 62/63 jurisprudence manifests the SC’s lack of faith in constitutionally nominated forums against whose decisions appeals lie to the

SC in any event. And it skews the balance of power between an unrepresentative court and elected executive/legislature.

From a legal perspective, the expansion of the SC’s discretionary authority has been at the expense of the fundamental rights of the accused. Since its introduction in 2010, a series of judgments has rendered Article 10A almost redundant. In the NS, IK and JKT rulings, the SC doesn’t even contemplate whether 184(3) ought to be construed differently post-10A. In reversing the burden of proof and holding that Article 13 (protection against self-incrimination) guarantee doesn’t apply to disqualification cases as the penalty isn’t of a criminal nature, the SC doesn’t consider that a false statement attracts a three-year jail term under ROPA.

The last casualty of this fresh jurisprudence is legal certainty. We don’t know which provisions of the constitution are to be read with subsidiary legislation and which are to be treated as standalone diktat. We don’t know which cases will fall within the domain of the ECP and/or high courts and which will be heard directly by the apex court. We don’t know which omissions will be deemed dishonest and which will be seen as harmless mistakes. We don’t know when the SC will become inquisitorial and when it will apply strict adversarial standards. And we no longer know which public outcries are justiciable and which aren’t.

Concluded

The writer is a lawyer based in Islamabad.

Email: sattar@post.harvard.edu

-

Prince William Plans For Monarchy Revealed As He Gears Up For ‘big Changes’

Prince William Plans For Monarchy Revealed As He Gears Up For ‘big Changes’ -

Rep. Al Green Removed From House Chamber During Trump’s State Of Union Address: Here’s What Happened

Rep. Al Green Removed From House Chamber During Trump’s State Of Union Address: Here’s What Happened -

Bill Gates Breaks Silence On Epstein Links, ‘took Responsibility For His Actions’ During Town Hall Meeting

Bill Gates Breaks Silence On Epstein Links, ‘took Responsibility For His Actions’ During Town Hall Meeting -

Christina Applegate Struggles To Leave Bed Amid Multiple Sclerosis Battle

Christina Applegate Struggles To Leave Bed Amid Multiple Sclerosis Battle -

Matthew McConaughey, Timothée Chalamet Predict AI Actors May Compete At Oscars By 2028

Matthew McConaughey, Timothée Chalamet Predict AI Actors May Compete At Oscars By 2028 -

Princess Eugenie Appears Unfazed By Andrew Drama In First Outing Since His Arrest

Princess Eugenie Appears Unfazed By Andrew Drama In First Outing Since His Arrest -

Gucci Faces Backlash For Using AI In New Spring Collection

Gucci Faces Backlash For Using AI In New Spring Collection -

Prince Harry, Meghan Markle Announce New Humanitarian Trip To Jordan

Prince Harry, Meghan Markle Announce New Humanitarian Trip To Jordan -

Prince Harry Is In All Out War With Meghan For Lilibet: It’s More Than The Sussexes Could Ever Generate’

Prince Harry Is In All Out War With Meghan For Lilibet: It’s More Than The Sussexes Could Ever Generate’ -

President Donald Trump Delivers The Traditional State Of The Union Address To Congress

President Donald Trump Delivers The Traditional State Of The Union Address To Congress -

Kyle Connor Focuses On Jets' NHL Season After Skipping Trump's White House Invite

Kyle Connor Focuses On Jets' NHL Season After Skipping Trump's White House Invite -

Why Prince William Grew Concerned About Meghan Markle's Conduct Shortly After Her Royal Wedding With Harry?

Why Prince William Grew Concerned About Meghan Markle's Conduct Shortly After Her Royal Wedding With Harry? -

Trent Williams Future With San Francisco 49ers Uncertain Ahead Of NFL Season

Trent Williams Future With San Francisco 49ers Uncertain Ahead Of NFL Season -

Australia: Bomb Threat Behind Evacuation Of PM Anthony Albanese Linked To Chinese Dance Group

Australia: Bomb Threat Behind Evacuation Of PM Anthony Albanese Linked To Chinese Dance Group -

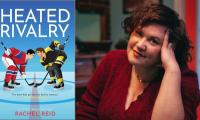

Rachel Reid Delays Release Of 'Heated Rivalry' Sequel 'Unrivaled' Due To Health Struggles

Rachel Reid Delays Release Of 'Heated Rivalry' Sequel 'Unrivaled' Due To Health Struggles -

British Royals ‘not Appreciated’ In Modern World, Says Author

British Royals ‘not Appreciated’ In Modern World, Says Author