KU’s foreign students tell all

Mohammad Alkamel becomes somewhat of a centre of attention whenever he goes to a mosque to pray. As a foreign student at the University of Karachi (KU), he has become used to the curious stares of fellow students but the one thing that he still finds uncomfortable is the barrage of questions about his faith that follow him even if he has just stepped out of the on-campus mosque.

“Most of our fellow students and the public inquire about our religion first even if we are right there praying with them in the mosque,” says Alkamel, a Sudanese student at the KU’s pharmacy department, who enrolled in the university in 2011.

According to Alkamel, African students such as him have to face a variety of odd questions at the varsity, but mostly people are unnecessarily interested in knowing their religion first before inquiring about their nationalities.

Talking to The News, he says the questions probably stem from the fact that people here know very little about African geography and culture and are interested in learning. “I think religion is a personal matter. But it seems that most Pakistanis like to think that they are better Muslims than others.”

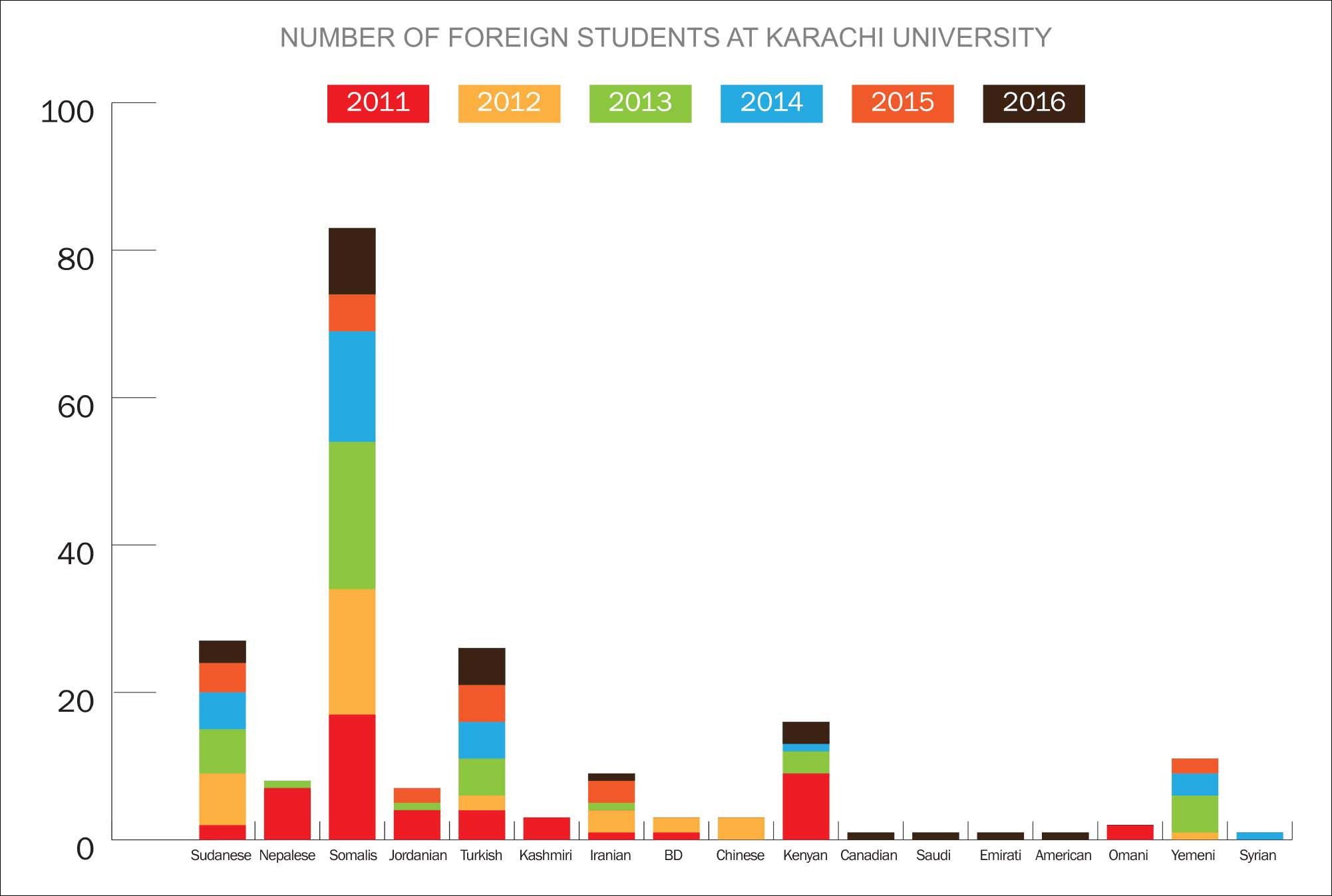

Alkamel is not the only foreign student to face such questions or other issues throughout his academic life in the country. Hundreds of students – mostly from Africa – enrolled at KU tell similar tales of discriminatory behaviour of fellow students and administration, trouble understating the medium of instruction and finding accommodation on campus.

“People call us Sheedi, a term that we know has derogatory connotations,” says Alkamel. “Some refer to as ‘Oh, kaalay’ (black person), while some make remarks about our curly hair wanting to touch them or asking if it’s real or fake hair.”

He says he has chosen Pakistan for higher education because education here is at a more advanced level than it is in his country, but he hasn’t received the support he was hoping for from the administration.

There also doesn’t seem to be much space at the university to increase awareness among local scholars about people from other nations who are studying side by side with them. According to Alkamel, Student Week was celebrated at the varsity in September where students from regional communities showcased their culture and traditions. However, African students were not given the opportunity to do so.

“When we approached the administration to request permission to host an Africa-centric event, the officials refused,” he says. Non-Muslim foreign students also face the same issues. For Brian Bergen from Kenya, the language barrier is the biggest hurdle – teachers and class fellows speak to him in Urdu and he does not understand the language.

Foreign students at a Karachi University canteen. Photo by author

Bergen complains that some classmates make jokes at his expense and even though he doesn’t understand the language, he can gauge the intent. “When I enter a classroom, my fellow students laugh at me and they talk among themselves about me in Urdu,” he says, adding that lectures are delivered in Urdu as well, making it impossible for him to keep up.

The student says he has approached KU’s foreign student office to find a solution to the issues he has been facing but has been unable to get his voice heard because no one there is willing to speak to him in English.

Because of the language barrier, Bergen is bound to the campus. “When I go outside the campus, police and other law-enforcement agencies ask for my passport or other identification documents.”

Much like Alkamel, the Kenyan student also has to deal with his share of intrusive questions. “I don’t mind when people ask about my religion. I am not a preacher. I just tell them I am non-Muslim.” He says exchange programmes are great opportunities for students but the authorities should make more of an effort to address the problems international students face.

African, not Baloch

Diini Hassan Osman is from Somalia but locals always assume that he is from Balochistan and talk to him in Balochi or Urdu, leaving him perplexed. “When Pakistani students find out I’m from abroad, they immediately ask about my religion and beliefs at once, which is not a good practise,” the final-year computer science student remarks. Talking about the security situation for foreign students, Osman believes it has become a lot better after the Karachi operation and they can now easily walk around or sit with friends at dhabas till late night without feeling unsafe.

Locals’ mischief

Mohammad Abdullah came to Pakistan on a scholarship from Yemen to study at the University of Peshawar. Since most of the lectures were held in Pashto, he made an attempt to learn the language. However, a friend who offered to help taught him Pashto curse words instead.

“When I said those words while talking to a teacher, I got a telling off,” he recalls. “Since then I have been careful about making new friends except those whom I know well.” Abdullah had to leave Peshawar around 2012 when the Yemeni Embassy asked its citizens to move from there because of the security situation.

He arrived in Karachi and enrolled at KU instead. The Yemeni student believes he has assimilated well into the city. He has learnt Urdu and the ways of the local communities. “When I wear shalwar kameez, I can pass off as a Punjabi. None can tell any difference.”

Residency woes

KU has set up only one hostel for foreign students near the campus’s Maskan gate. And even though they pay up to Rs24,000 in annual fees, it still lacks basic facilities. A mound of garbage sits right outside the hostel’s rooms, there is only one washroom for students living on all three floors and stray animals roam the halls freely at night.

“In the mornings, we have to wait for a long time and queue up outside to be able to use it. Even the water storage tank is full of mud,” says Abdullah. “It is very difficult staying here. No one cares about the students’ needs.”

Because of the hostel’s condition, many foreign students are forced to rent rooms outside. But off-campus they have to face another problem – money minters who charge them exorbitant rates for rent and food.

“When homeowners come to know that we are foreigners, they demand Rs8,000 to Rs10,000,” says Osman from Somalia. “They assume African students are rich when really a majority of us belong to middle-class families.” He adds that despite this, even if the KU admin offers him a hostel room free of charge, he would prefer to stay off campus.

The officials’ stance

The university is facing severe financial constraints because of which it is unable to address many problems faced by foreign students regarding the hostel in real time, KU Registrar Dr Munawar Rasheed told The News earlier this month.

He said that at the time of admission students are given the choice of staying at the hostel of off-campus. “If students start facing problems after joining, we can hardly exempt them from paying their tuition fee,” he said, adding that the issues of foreign students should be addressed between the governments.

When asked about the medium of instruction being Urdu and thereby hard for foreigners to keep up with, the registrar said that officially the medium of instruction in the university was English but he was aware that Urdu was more commonly used in classes.

He claimed that it had been decided that foreign students would be required to take a one-year English language course and the policy would be implemented from the next academic year. This response, however, did not address students’ concerns that they cannot keep up with Urdu lessons.

Rasheed conceded that the foreign students’ office was not doing its part for the students but maintained that the varsity’s financial situation was the reason behind it.

The foreign students meanwhile continue to head to the Urdu-dominated lectures and traverse the rather unwelcoming academic and administrative atmosphere in a place they have chosen to make a second home, hoping for things to get better for them or those who come to the city after them.

-

'Too Hard To Be Without’: Woman Testifies Against Instagram And YouTube

'Too Hard To Be Without’: Woman Testifies Against Instagram And YouTube -

Kendall Jenner Recalls Being ‘too Stressed’: 'I Want To Focus On Myself'

Kendall Jenner Recalls Being ‘too Stressed’: 'I Want To Focus On Myself' -

Dolly Parton Achieves Major Milestone For Children's Health Advocacy

Dolly Parton Achieves Major Milestone For Children's Health Advocacy -

Oilers Vs Kings: Darcy Kuemper Pulled After Allowing Four Goals In Second Period

Oilers Vs Kings: Darcy Kuemper Pulled After Allowing Four Goals In Second Period -

Calgary Weather Warning As 30cm Snow And 130 Km/h Winds Expected

Calgary Weather Warning As 30cm Snow And 130 Km/h Winds Expected -

Maura Higgins Reveals Why She Wears Wigs On 'The Traitors' And What Her Real Hair Is Like

Maura Higgins Reveals Why She Wears Wigs On 'The Traitors' And What Her Real Hair Is Like -

Brandi Glanville Reveals Shocking Link Of Facial Issues To Leaking Implants, Claims 'no' Support From Ex Eddie Cibrian

Brandi Glanville Reveals Shocking Link Of Facial Issues To Leaking Implants, Claims 'no' Support From Ex Eddie Cibrian -

Who Is Rob Rausch’s Girlfriend? 'The Traitors' Winner Linked To Kansas City Woman

Who Is Rob Rausch’s Girlfriend? 'The Traitors' Winner Linked To Kansas City Woman -

Bobby J. Brown, 'Law & Order' And 'The Wire' Actor, Dies At 62

Bobby J. Brown, 'Law & Order' And 'The Wire' Actor, Dies At 62 -

Netflix Gives In As Paramount Offers Massive Breakup Fee To Step Away From Warner Bros. Discovery Bid

Netflix Gives In As Paramount Offers Massive Breakup Fee To Step Away From Warner Bros. Discovery Bid -

Who Won 'Traitors' Season 4? Rob Rausch Claims $220,800 Grand Prize

Who Won 'Traitors' Season 4? Rob Rausch Claims $220,800 Grand Prize -

Niall Horan Shares Update On New Music On The Way

Niall Horan Shares Update On New Music On The Way -

Backstreet Boys Member Brian Littrell Refiles Trespassing Lawsuit Against Florida Retiree

Backstreet Boys Member Brian Littrell Refiles Trespassing Lawsuit Against Florida Retiree -

Kate Middleton Dubbed ‘conscious Shopper’ By Famous Fashion Expert

Kate Middleton Dubbed ‘conscious Shopper’ By Famous Fashion Expert -

Princess Catherine Joins Volunteers In Newtown During Powys Visit

Princess Catherine Joins Volunteers In Newtown During Powys Visit -

Shamed Andrew Thought BBC Interview Was ‘time To Shine,’ Says Staff

Shamed Andrew Thought BBC Interview Was ‘time To Shine,’ Says Staff