The destiny of the Quetta report

The latest spasm of optimism among incurably romantic Pakistanis is sourced in the Quetta Commission report authored by Supreme Court Justice Qazi Faez Isa. We have done this routine many, many times. The very release of the document signifies a degree of institutional autonomy. True, kind of. The articulation of a damning indictment of the system as it exists is the first step in the eventual reforms needed to make the system better. Okay, perhaps.

As a Pakistani romantic, one is more than capable of seeing the silver lining in the dark cloud that is the Quetta Commission report. But do something often enough and it risks becoming banal and vapid. Notwithstanding the importance of holding onto hope and the ability to correctly identify progress, against a tide of bad news, we should cease cultivating the fiction that Pakistani state and society are on the cusp of systemic reform on the back of a sober analysis, of the kind that Justice Qazi Faez Isa has provided in his important report.

Less than 18 months ago, the Judicial Commission report on the elections was released. It was the only material gain that Imran Khan and the PTI managed to extract from the system after the infamous dharna of 2014. What progress can we soberly report on electoral reform since then? Not a lot. The vehicle for reform is politics, but a political discourse needs a memory longer than the duration of a narcotic-induced high to deliver real reform.

The structural reforms that the 18th Amendment delivered came about as a product of a long-term political commitment to a difference-making compact that would squeeze the space for external interventions in Pakistani politics. So much has been written about all the wonderful things that the Charter of Democracy has helped deliver, but there is much that has not been delivered. In addition, there is much that the 18th Amendment has done that will eventually be undone. Not as a rebuke to the principals or values that underwrote the charter or the idea of federalism, but as a response to the needs of a changing Pakistan. When will the remaining items on the CoD be delivered? And when will weaknesses incorporated by the 18h Amendment be fixed? Probably when the appropriate quantum of political capital is invested in that effort.

Since the 2013 election, the PTI has undermined its chances at achieving a national electoral victory in the future by allowing political ADHD to distract it from the two core issues that would have (and may yet) help it mobilise power in the 2018 election. These two core issues are, first, meaningful reform of the election commission, and second, an expedited census, including the potential redrawing of the constituency map. Of course, the PTI would have been more able to focus on an agenda of transformative change if the leadership of the party was less obsessed with the short-term high of RTs and talk show ratings, and more focused on acquiring high office through a dispassionate assessment of its strengths, and weaknesses. Instead, in a country that is overflowing with bribes and payments to lubricate bureaucratic processes on every street, across every manner of private and public transaction and in every institution, the PTI has chosen to go back to the future and relive the failed strategy of fighting corruption as its unique selling proposition, its big idea.

In the late 1990s, when many of today’s adolescent supporters of the PTI were not yet conceived, an elder generation of angry young people raised the stature of mainstream pop songs like Ehtesab and Fraudiyay to anthem status. By doing so, we unwittingly helped hoodwink Imran Khan into believing that his outstanding fiduciary reputation would help catapult him to the top of the political heap – especially given the poor fiduciary reputations of his principal opponents back then, Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto. It is déjà vu all over again. This is the price of not paying attention. Instead of continuing to foam at the mouth in incandescent rage at critics of their party, PTI supporters may consider a sober analysis of the quality of their leadership (rather than the quality of their leader).

In July 2013, it was as if Allah had chosen to bless Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif with a welcome gift. The Abbottabad Commission report happened to be leaked to Al Jazeera, and much like the reaction to the Quetta Commission report, the loins of those that are easily excited by technical analyses of Pakistan’s institutional ills were stirred (full disclosure: much as I may pretend otherwise, I am among those romantics). Three and a half years since the Abbottabad Commission, we should know better than to be seduced by the words in a commission report.

From the evidence of the last three decades, there seem to be essentially two ways to achieve transformative impact in governing Pakistan. Ironically, they represent competing theories of how history is made. The first is the emergence and mobilisation of grand political compacts: like the Charter of Democracy, which one may attribute to the product of a society’s collective wisdom. The second is the exercise of enduring executive power, or the ‘Great Man Theory’. Herbert Spencer was derisively critical of Thomas Carlyle’s idea that history is a collection of the life stories of “great men”. Over a century and a half after the debate, we have the luxury of being to say that it’s a little bit of that and a little bit of this.

Under PM Sharif, the great man is Shahbaz Sharif. His model of finding civil servants that can deliver specific assignments in miraculous time frames is the driving mechanism for how the PML-N government sees governance. Deliver enough megawattage and enough road and transport infrastructure, and voters will forgive many sins, perhaps even Panama. The enduring legacy of this era of governance will not just be the concrete and metal that this government will leave behind. It will be the idea that delivering ambitious projects is very much possible, within the constraints of a bureaucracy and administrative infrastructure that even Fawad Hassan Fawad, Younus Dagha and Ahad Cheema know is completely broken. Indeed, the very root of their effectiveness and power is that the system is completely broken. No textbook can capture skewed institutional incentives better than the bureaucracy’s dynamics under the Sharifs.

Of course, all of this is boring, complicated and inconvenient. Provincial capacity, a major topic of both the Abbottabad Commission and Quetta Commission reports, is a function of these bureaucratic dynamics. Fixing all of this will require large numbers of PhDs, former and serving bureaucrats, and anthropologists and economists to argue for hours and hours and hours. And come up with rafts of both analysis and options that create a new path forward for how the country is governed.

Of course, it may just be easier to blame the ISI for not wanting Nacta, blame ISPR for not equipping the information ministry to be competent, blame the Americans for being pro-army instead of appointing competent people to manage that relationship and, voila, one may avoid the conversation of reform altogether. Nothing is more convenient than continuing to plumb deep into our civ-mil disequilibrium, instead of investing the effort to undo it. Competently.

In the meantime, whether you are more convinced by Carlyle’s arguments or Spencer’s, neither Nawaz Sharif nor Pakistani society are about to write history. The Quetta Commission report is destined for the same place that PM Sharif placed the Abbottabad Commission report. In a cold, dark drawer that nobody will ever open.

The writer is an analyst and commentator.

-

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

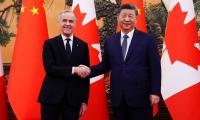

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training -

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light -

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push -

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down -

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career -

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer -

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis -

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI -

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds -

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years -

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome