Fulfilling Pakistan’s promise

The political landscape of British India in the early 20th century was shaped by a complex interplay of colonial rule, emerging nationalist sentiments, and communal tensions. The formation of the All-India Muslim League in 1906 was a pivotal moment in this landscape, reflecting the growing awareness among some sections of the Muslim elite — comprising the landed upper classes and intelligentsia — of the need for a distinct political voice.

The Muslim League was established with the primary objective of safeguarding the political, economic, and cultural rights of Muslims, who constituted a significant minority in a predominantly Hindu-majority India.

The initial objectives of the Muslim League were driven by the fear of Muslim marginalisation within a united Indian nation-state. The League advocated for separate electorates — a quota system — arguing that this mechanism would ensure fair representation and protect Muslim interests in a system where they were outnumbered and, at the same time, economically and socially backward.

This demand stemmed from the belief that backward Muslims, as a distinct religio-social group, would not be able to have a meaningful say in a Hindu-majority India, and would lack equal opportunities to overcome poverty. The call for separate electorates became a key point of contention, highlighting the deep-seated communal divisions that would later shape the course of Indian politics.

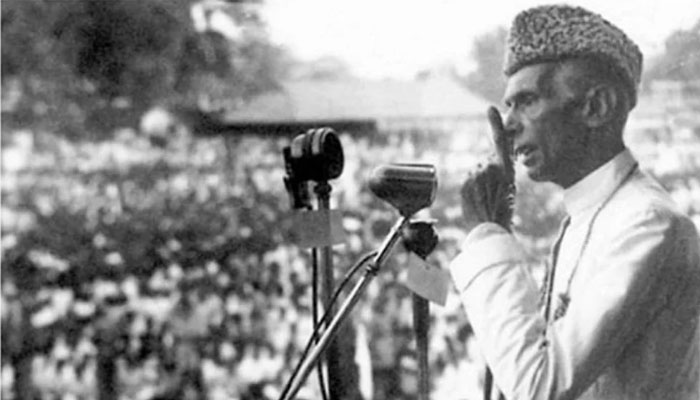

The evolution of the Muslim League's demands — from seeking separate electorates to advocating for a separate Muslim state — culminated in the

passing of the historic Lahore Resolution of 1940. This resolution, often referred to as the Pakistan Resolution, marked a significant shift in the League's political strategy.

It articulated a clear vision for a ‘separate states’ where Muslims could live according to their religious, cultural and political ideals. The resolution was driven by the conviction that Muslims and Hindus constituted two distinct nations, each with its own unique identity and aspirations.

The Lahore Resolution had a profound impact on the broader Indian independence movement. It highlighted the growing divide between the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress, which advocated for a united, secular India but struggled to overcome Hindu-centric sentiments within its own ranks. The outbreak of the Second World War and the British ‘divide-and-rule’ policy further deepened communal divisions, intensifying the debate over the future of India. The League's demand for a separate state gained traction among Muslim middle classes, who felt increasingly alienated from the Congress-led nationalist movement.

Although the Muslim League did not hold a single procession against colonial rulers between 1940 and 1945, it gained popularity among the Muslim middle class due to growing communal sentiments and the fear of Hindu dominance in an undivided India. Thus, it won elections based on separate electorates, with voters possessing specific qualifications.

The creation of Pakistan in 1947 was a monumental achievement for the Muslim League, marking the establishment of a separate state for Muslims. This historic event could have been transformed into a significant success by developing a new identity for Pakistan as a strong federation that did not align itself with any religion — creating an environment conducive to democratic participation under rule of law.

Unfortunately, the new country fell into the hands of the colonial-era administrative structures, which had little understanding of the ideals espoused by the 1940 resolution or the kind of country that could have been developed. Its main focus remained on administrative measures rooted in British colonial machinery, distorting the original vision from the very beginning and continuing to do so to this day.

Undemocratic mindsets, narrow attitudes, and policies formed the basis of the language dispute in Bengal, which was mishandled. Nationalistic sentiments, alongside other injustices, set the stage for the dismemberment of Pakistan from the early days of its creation.

One critical aspect, which is essential to understand, is that from the very beginning, Pakistan was controlled by a civil and military bureaucratic structure that did not allow the development of political parties with genuine roots among the people. This hindered the creation of a stable democratic system, and this situation persists to this day. The existing so-called political parties are, in essence, interest groups, disconnected from the people of Pakistan and indifferent to the country’s future.

Another failure was the inability to develop a social, economic, and cultural system that was inclusive in nature. However, the new leadership, which was a product of the colonial system, adhered to a distorted neo-colonial framework, in which Pakistan remained a client state.

Thankfully, the entire sci-tech landscape has evolved, bringing with it a positive globalising impact. In the era of General AI, it is now absolutely essential for outdated leadership to engage in deep introspection, abandon antiquated practices, and embrace a process of globalisation in information, knowledge, research, innovation, and development (IKRID). This shift is crucial for creating a robust sci-tech-human power complex. Moreover, inclusive policies must be implemented to ensure that every individual and city in Pakistan is actively involved in the nation’s development and progress.

Ultimately, a very serious question remains for the real rulers of Pakistan to answer: Why have generations of the poor been unable to escape abject poverty since 1947? Consider the peripheral rural areas of all four provinces and Gilgit-Baltistan, and then answer this question.

Metrics such as economic stabilisation, growth rate and tax-to-GDP ratio are meaningless to the majority of people who still live in poverty. Offering them progress through the ‘trickle-down effect’ is not only ridiculous but also dehumanising.

It is an undeniable fact, so evident to the naked eye that it cannot be ignored, that Generative AI and other transformative technologies have the potential to transform any country, regardless of its current challenges, into a vibrant and inclusive system, people and the country.

The writer is an advocate of the high court and a former civil servant.

-

Savannah Guthrie Mom Update: Unexpected Visitors Spark Mystery Outside Nancy's Home

Savannah Guthrie Mom Update: Unexpected Visitors Spark Mystery Outside Nancy's Home -

Elle Fanning Shares Detail About Upcoming Oscars Night Plan With Surprise Date

Elle Fanning Shares Detail About Upcoming Oscars Night Plan With Surprise Date -

Demi Lovato Spills Go-to Trick To Beat Social Anxiety At Parties

Demi Lovato Spills Go-to Trick To Beat Social Anxiety At Parties -

Benny Blanco Looks Back At The Time Selena Gomez Lost Her Handrwritten Vows Days Before Wedding

Benny Blanco Looks Back At The Time Selena Gomez Lost Her Handrwritten Vows Days Before Wedding -

Naomi Watts Reveals Why She Won't Get A Facelift In Her 50s

Naomi Watts Reveals Why She Won't Get A Facelift In Her 50s -

Travis Kelce's Mom Donna Fires Back At Critic With Sarcastic Reply After Body Jab

Travis Kelce's Mom Donna Fires Back At Critic With Sarcastic Reply After Body Jab -

Kendall Jenner Gets Candid About Her Differences With The Kardashian Clan Over Style Choices

Kendall Jenner Gets Candid About Her Differences With The Kardashian Clan Over Style Choices -

Sam Altman Opens Up About OpenAI, Anthropic, Pentagon Conflict

Sam Altman Opens Up About OpenAI, Anthropic, Pentagon Conflict -

Brenda Song Confesses Fascination With Conspiracy Theories

Brenda Song Confesses Fascination With Conspiracy Theories -

Lunar Eclipse 2026: Time, Date, Sighting Locations, Know Every Detail

Lunar Eclipse 2026: Time, Date, Sighting Locations, Know Every Detail -

Death Toll Climbs To 54 As Floods Wreck South-eastern Brazil

Death Toll Climbs To 54 As Floods Wreck South-eastern Brazil -

Katie Price Drops Bombshell Plan To Cash In On Marriage

Katie Price Drops Bombshell Plan To Cash In On Marriage -

Ryan Gosling Shares How Daughters' 'honest' Feedback Keeps Him Grounded

Ryan Gosling Shares How Daughters' 'honest' Feedback Keeps Him Grounded -

Neve Campbell Explains Why She Avoids Watching Scary Movies As She Returns To 'Scream 7'

Neve Campbell Explains Why She Avoids Watching Scary Movies As She Returns To 'Scream 7' -

Milan Tram Crash Leaves Two Dead, 39 Injured

Milan Tram Crash Leaves Two Dead, 39 Injured -

Timothee Chalamet Touches On His Personality's Relatability With 'Marty Supreme' Role

Timothee Chalamet Touches On His Personality's Relatability With 'Marty Supreme' Role