Policy rate caution

SBP’s reluctance to cut rates aggressively is often justified by fears of an import surge

The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) and the current economic team of the government of Pakistan must stop hiding behind a veil of overly cautious monetary policies.

The latest Monetary Policy Statement (MPS) issued on January 27, 2025, which reduced the interest rate by a mere 1.0 per cent, from 13 per cent to 12 per cent, is emblematic of the government’s inability to act with the decisiveness that Pakistan’s economy desperately needs. Even with inflation expectations capped at 7.5 per cent for FY25, the real interest rate remains excessively high, stifling economic recovery and missing a golden opportunity to catalyze sustainable growth.

The SBP and the government continue to anchor their policy decisions in an exaggerated narrative of economic risks, despite their own data demonstrating a stable macroeconomic environment. Inflation, which hit 4.1 per cent in December 2024, is expected to rise moderately, peaking at 7.5 per cent (a maximum) by year-end. Even with this forecast, the SBP had room to significantly reduce the policy rate to 10.5 per cent, maintaining a real interest rate of 3.0 per cent, a standard practice in conventional economics. Yet, they chose to play it overly safe.

The real interest rate in Pakistan currently hovers at 7.9 per cent – one of the highest globally – at a time when most emerging economies are cutting rates to fuel economic activity. This hyper-cautious stance not only inhibits domestic investment and consumption but also imposes unnecessary costs on the government through increased debt servicing.

The SBP’s reluctance to cut rates more aggressively is often justified by fears of an import surge, which could destabilize the current account. This argument, however, is contradicted by the very data the SBP cites in its statement. The current account surplus of $1.2 billion in H1 FY25, supported by robust remittances and export earnings, leaves room to accommodate a modest increase in imports, particularly if those imports are linked to productive sectors like exports.

The government has also demonstrated its ability to control speculative forces in the currency market through anti-smuggling measures and cracking down on illicit money changers. Similar targeted policies could easily regulate non-essential imports, freeing up space for a more growth-oriented monetary policy.

The SBP and government’s overly cautious stance perpetuates a cycle of economic underperformance. By failing to reduce rates to 10.5 per cent, they have missed three critical opportunities: one, lower debt servicing costs. With Pakistan’s ballooning debt burden, every basis point in interest rates matters. A reduction to 10.5 per cent could have significantly reduced the government’s debt servicing expenses, freeing up fiscal space for development spending.

Two, stimulated economic activity. A lower interest rate environment would have spurred private sector borrowing and investment, driving economic activity, job creation, and ultimately, higher tax revenues.

Three, boosted exports. Cheaper credit for exporters could have enabled them to expand production capacity and improve competitiveness in international markets, directly contributing to a more sustainable current account position.

The government and the SBP appear to be operating under a pervasive insecurity that has long plagued Pakistan’s economic managers. Despite having a stable macroeconomic outlook, they continue to act as though the economy is on the brink of collapse. This lack of confidence is reinforced by their submission to the interests of local economic elites – primarily commercial banks – that thrive on high-interest rates and have little incentive to support broader economic growth.

Even within the confines of conventional economics, there was ample justification for reducing the policy rate to 10.5 per cent. For a country aspiring to grow its economy, create jobs, and improve living standards, this level of caution is not only unnecessary but counterproductive. The SBP and the government must recognise that bold, growth-oriented policies are not just an option but a necessity.

Pakistan is not a fragile state – it is a resilient nation with immense untapped potential. What we lack is not capacity or opportunity but the courage and vision to act decisively. It is time for the SBP and the economic team to stop playing defence and start leading with the confidence and ambition that Pakistan deserves.

The SBP’s modest rate cut is emblematic of a broader issue: an inability to take bold, game-changing decisions. Pakistan’s policymakers must shift from a mindset of managing crises to one of seizing opportunities. By cutting rates to 10.5 per cent, the government could have set the stage for a virtuous cycle of growth, reduced fiscal pressures and enhanced exports. Instead, they chose to err on the side of caution, once again deferring the promise of a brighter economic future.

Let this be a wake-up call to Pakistan’s economic managers: the time for incrementalism is over. If Pakistan is to thrive, it must embrace bold reforms and policies that reflect the strength, resilience, and potential of its people. Only then can we break free from the shackles of insecurity and chart a path toward sustainable, inclusive prosperity.

The writer is a consultant at various large companies, and teaches financial markets in Pakistan. He can be reached at: hissan3@gmail.com

-

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

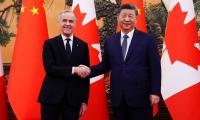

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training -

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light -

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push -

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down -

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career -

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer -

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis -

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI -

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds -

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years -

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome