Between the gavel and the streets: Pakistan’s 2024 Yearender

Analysts predicted matter would escalate to courts and it did

KARACHI: While this year has seen more than a fair share of political protests and discourse, it would not be wrong to call this a year dedicated to Pakistan’s courts and judges — judges delivering verdicts, judges writing letters, and judges caught in the political crosshairs.

Through it all, Imran Khan remained the central figure, whether as a spectre haunting power corridors or a symbol of political idealism for his supporters, dominating headlines once again this year in most of the legal debates as well.

From the fallout of the general elections in February to constitutional amendments that reshaped the judiciary, 2024 has been a year of uncertainty for the country. Political protests, economic instability, and deteriorating relations with neighbours further complicated the situation.

Mostly marked by significant legal battles and judicial decisions, the year saw controversies beginning in February and continuing right through December. From the PTI’s bid for reserved seats to the retirement of Chief Justice Qazi Faez Isa, we saw pivotal moments that reshaped its legal and judicial landscape. Here’s a look at 2024’s politics through the legal lens.

The year started with a huge blow to the PTI when the Supreme Court -- in a rather dramatic near-midnight verdict -- upheld the ECP’s decision to bar the party from using its iconic cricket bat electoral symbol in the February 8 general election. Another significant blow came with a trial court convicting Imran Khan and Shah Mahmood Qureshi in the cipher case at the end of January, sentencing them to 10 years in prison just days before the general elections.

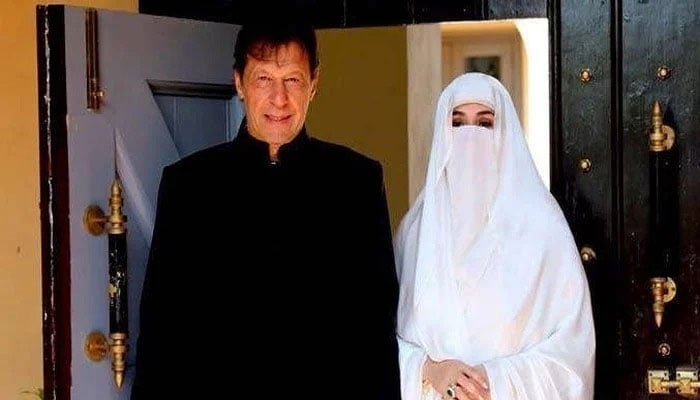

It didn’t end there: this was followed by Imran and his wife, Bushra Bibi, being found guilty in the Toshakhana case and sentenced to 14 years in prison. Perhaps the most uncomfortable and widely panned verdict came on February 3, when Imran and Bushra Bibi were convicted in the controversial iddat case, and sentenced to another seven years in prison.

Next came the February 8 general elections -- marred by allegations of rigging and unrest and dominating politics right down to today, December 31.

Deprived of its election symbol, the PTI had contested as ‘independents’ who -- despite all the allegations of rigging -- ended up securing over 100 of the 226 seats, making it the largest bloc in a hung parliament. True to form, the party refused to align with the PPP and we eventually got a coalition government led by the PML-N and PPP, with Shehbaz Sharif taking the helm as prime minister.

Right after the much-maligned Feb 8 election started what we can easily call the Reserved Seats Saga with the PTI, through its alliance with the Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC), seeking to secure 77 reserved seats in the National Assembly allocated to women and minorities. Experts warned that denying the PTI these seats could leave parliament incomplete, jeopardising key legislative functions, including elections for the prime minister and speaker.

However, in a 4-1 decision, the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) declared the PTI-SIC alliance ineligible for the reserved seats, redistributing them among other parties. The verdict sparked a wave of criticism from legal experts, who argued that the Election Rules of 2017 mandated a proportional allocation of reserved seats based on a party’s electoral performance. Analysts predicted the matter would escalate to the courts -- and it did.

Lady luck finally smiled on Imran in July, with a trial court acquitting Imran and Bushra Bibi in the iddat case, Imran securing the suspension of his Toshakhana sentence, bail in the £190 million corruption case, and an acquittal in the cipher case by the Islamabad High Court (IHC). In July, the Supreme Court also granted the PTI reserved seats for women and minorities, positioning it as the largest party in parliament -- a verdict the coalition government resisted implementing.

In a rare instance of military accountability, former ISI chief Lt Gen (r) Faiz Hameed was arrested in August on charges of abuse of power and involvement in the May 2023 protests. Charged in December and tried under the Pakistan Army Act, he became the first ex-ISI chief to be formally charged with meddling in political affairs, marking a shift in institutional power dynamics.

As February’s controversial elections gave way to parliamentary disputes, the judiciary found itself at the heart of the political storm, further underscored by amendments and rulings that reshaped its structure. October saw the controversial 26th Amendment that introduced amendments regarding the tenure and appointment of the chief justice of Pakistan (CJP), the evaluation of judges’ performances, and the creation of constitutional benches within the Supreme Court. Legal opinion on the 26th Amendment stood divided, with proponents highlighting the benefits of limiting judicial discretion, introducing parliamentary oversight, and monitoring judicial performance. Critics, however, feared that the amendments could lead to political interference in judicial appointments, create internal divisions, and undermine judicial independence and that the constitutional benches could be manipulated for political gains.

Justice Yahya Afridi’s appointment as the chief justice of Pakistan sparked PTI-led criticism, protest and outrage which was amplified later by the appointment of Justice Amin-ud-Din Khan as head of the newly formed constitutional bench.

The judiciary also took steps towards accountability, with the Supreme Court overturning Justice Shaukat Aziz Siddiqui’s dismissal and the Supreme Judicial Council ruling that Justice Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi’s resignation amid misconduct allegations should have led to dismissal.

(Former) CJP Qazi Faez Isa retired on October 25, leaving behind a mixed legacy of landmark rulings and controversial decisions. Simultaneously, legislative amendments continued to shape the judiciary, including changes to the Supreme Court (Practice and Procedure) Act, 2023, which aimed to streamline judicial processes. Through it all, there was a flurry of letters written by the higher judiciary -- oddly enough, to each other -- which ended up only adding to the growing fears of a divided judiciary.

Needless to say, 2024 was punctuated by a series of protests led by the PTI. Centred on demands to revoke the 26th Amendment, restore democracy, reclaim the public mandate, and release political prisoners, these protests often turned violent. Other parties too took to the streets on more than one occasion. But perhaps the most intense of 2024 PTI protests were seen between September and November -- polarisation at its peak and the PTI’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Chief Minister Ali Amin Gandapur at a fiery high.

The PTI’s protesting year ended unfortunately on a sombre note. The ‘Final Call’ protest in November became a symbol of polarisation, as deadly clashes painted a grim picture of Pakistan’s fractured political landscape. The PTI ended up claiming a heavy death toll though independently verified accounts gave a less stark but equally tragic loss of life; five security personnel too lost their lives during the November protest. December saw the return of the debate on military trials for civilians, with military courts sentencing around 75 civilians over the May 9 riots.

As the year ends, Pakistan finds itself at a crossroads: a judiciary reshaped by controversy, a political landscape marred by polarisation, and a public weary of unending turmoil. One silver lining? An economy on the bend.

-

Bridgerton’s Michelle Mao On Facing Backlash As Season Four Antagonist

Bridgerton’s Michelle Mao On Facing Backlash As Season Four Antagonist -

King Charles Gets New ‘secret Weapon’ After Andrew Messes Up

King Charles Gets New ‘secret Weapon’ After Andrew Messes Up -

Shia LaBeouf Makes Bold Claim About Homosexuals In First Interview After Mardi Gras Arrest

Shia LaBeouf Makes Bold Claim About Homosexuals In First Interview After Mardi Gras Arrest -

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie ‘strained’ As They Are ‘not Turning Back’ On Andrew

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie ‘strained’ As They Are ‘not Turning Back’ On Andrew -

Benny Blanco Addresses ‘dirty Feet’ Backlash After Podcast Moment Sparks Online Frenzy

Benny Blanco Addresses ‘dirty Feet’ Backlash After Podcast Moment Sparks Online Frenzy -

Sarah Ferguson Unusual Trait That Confused Royal Expert

Sarah Ferguson Unusual Trait That Confused Royal Expert -

Prince William, Kate Middleton Left Sarah Ferguson Feeling 'worthless'

Prince William, Kate Middleton Left Sarah Ferguson Feeling 'worthless' -

Ben Affleck Focused On 'real Prize,' Stability After Jennifer Garner Speaks About Co Parenting Mechanics

Ben Affleck Focused On 'real Prize,' Stability After Jennifer Garner Speaks About Co Parenting Mechanics -

Luke Grimes Reveals Hilarious Reason His Baby Can't Stop Laughing At Him

Luke Grimes Reveals Hilarious Reason His Baby Can't Stop Laughing At Him -

Why Kate Middleton, Prince William Opt For ‘show Stopping Style’

Why Kate Middleton, Prince William Opt For ‘show Stopping Style’ -

Here's Why Leonardo DiCaprio Will Not Attend This Year's 'Actors Award' Despite Major Nomination

Here's Why Leonardo DiCaprio Will Not Attend This Year's 'Actors Award' Despite Major Nomination -

Ethan Hawke Reflects On Hollywood Success As Fifth Oscar Nomination Arrives

Ethan Hawke Reflects On Hollywood Success As Fifth Oscar Nomination Arrives -

Tom Cruise Feeling Down In The Dumps Post A Series Of Failed Romances: Report

Tom Cruise Feeling Down In The Dumps Post A Series Of Failed Romances: Report -

'The Pitt' Producer Reveals Why He Was Nervous For The New Ep Of Season Two

'The Pitt' Producer Reveals Why He Was Nervous For The New Ep Of Season Two -

Maggie Gyllenhaal Gets Honest About Being Jealous Of Jake Gyllenhaal

Maggie Gyllenhaal Gets Honest About Being Jealous Of Jake Gyllenhaal -

'Bridgerton' Star Luke Thompson Gets Honest About Season Five

'Bridgerton' Star Luke Thompson Gets Honest About Season Five