Two-Nation theory and its significance for Pakistan today

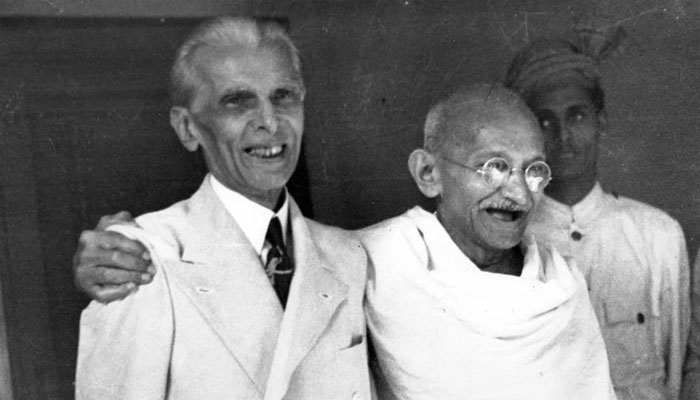

It was Jinnah alone who possessed vision, determination, and ability to achieve what others deemed impossible

Muhammad Ali Jinnah was a leader destined for greatness, steadfastly adhering to his principles and beliefs. This unwavering commitment earned him admiration as a resolute visionary among his supporters and criticism as a rigid figure among his detractors. Pakistan was the product of his imagination and determination-a creation that seemed inconceivable not only to the British, the Indian National Congress (INC), and other Hindu leaders but also to many Muslims and members of the All-India Muslim League. Yet, it was Jinnah alone who possessed the vision, determination, and ability to achieve what others deemed impossible.

Pakistan was not established on traditional grounds such as geography, ethnicity, language, or race. Instead, it was founded on the principles of religious identity and minority rights. Jinnah’s lifelong advocacy for minorities, particularly Muslims, culminated in his success in carving out a separate homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent. This vision was clearly articulated in his landmark speech on August 11, 1947, where he declared:

“You are free; you are free to go to your temples, mosques, or any place of worship. We are all citizens and equal citizens of this state.”

Jinnah’s dedication to minority rights, especially Muslim rights, guided South Asia towards the creation of a separate Muslim state, Pakistan. His pivotal role in the Lucknow Pact of 1916 demonstrated his ability to unite opposing factions and secure crucial concessions for Muslims in South Asia. This agreement not only brought the Muslim League into the political mainstream but also established Jinnah as a leader of extraordinary political acumen.

Another significant aspect of Jinnah’s leadership was his expertise in constitution-making, a skill recognised even by his opponents. The Indian National Congress acknowledged this by inviting him to contribute to drafting India’s future constitution. Jinnah further demonstrated his proficiency through the historic Fourteen Points. Many of these points were not only accepted by the British and incorporated into the Government of India Act of 1935 but also influenced the constitutions of both India and Pakistan.

The Fourteen Points clearly articulated the demands and aspirations of Muslims of the subcontinent while addressing the concerns of other minorities in British India. Jinnah’s vision included key proposals such as Sindh’s separation as a province-a pivotal step in Pakistan’s eventual establishment-and political reforms in NWFP and Balochistan, which empowered the long-neglected populations of these regions. Additionally, he emphasised the principle that any constitutional change should require the approval of three-fourths of the affected group. Each point underscored Jinnah’s political foresight and deep understanding of the needs of the subcontinent’s diverse communities.

Jinnah assumed leadership of the All-India Muslim League at a critical juncture in history. The Indian National Congress (INC) had secured a majority in the 1937 elections, while the League struggled to win even in Muslim-majority areas. Despite these challenges, Jinnah guided the League through one of its darkest periods, using every available means to establish its prominence. He addressed large gatherings, wrote extensively in newspapers, and met with influential figures and common citizens alike, transforming the League into the final hope for the Muslims of the subcontinent.

Jinnah’s tireless efforts culminated in a revolutionary shift in South Asian politics, epitomised by the adoption of the Pakistan Resolution in 1940. While other politicians, such as Raja Gopal Achari, had proposed ideas for independence from British rule, the Pakistan Resolution marked a decisive direction for the League and the Muslim community under Jinnah’s leadership. Critics sought to discredit Jinnah as a traitor, accusing him of demanding a “Country within a country.” However, his call for Pakistan was not rooted merely in political strategy but in the natural and urgent need for a peaceful and prosperous future for the Muslims of the subcontinent.

The 1940s, an era of the ongoing war, made it evident to the British that their rule in India was nearing its end. So they started devising a plan to maintain influence and hegemony in India even after formally relinquishing its control. Proposals like the Cripps Mission of 1942 aimed at to retain a semblance of British authority, but Jinnah consistently demanded complete sovereignty, refusing any arrangement that would perpetuate subservience to white supremacy.

Jinnah was also deeply conscious of the future leadership of Muslims. He vehemently opposed any arrangement that allowed the Congress to represent Muslims, not even through its Muslim members. He believed that identities such as national or ethnic-promoted by Congress or regional factions like Bengal-were insufficient to safeguard Muslims’ rights. For this reason, he rejected the Congress’ proposal at the Simla Conference to share Muslim seats, suggesting four representatives from the League and one from Congress.

History testifies that no one in the League could match Jinnah’s steadfast adherence to the ideology of the Two-Nation Theory, which posited Muslims and Hindus as distinct nations. Jinnah resisted any dilution of the Muslim identity, even when it antagonised the British, who were reluctant to accept the creation of a state rooted in religion, specifically Islam.

Jinnah’s unparalleled leadership was the cornerstone of the Pakistan Movement. Without him, the creation of Pakistan might have been possible, but when, where, and how it would have materialised remains unimaginable.

-

Ryan Coogler Shares Thoughts About Building Community Of Actors Amid 'Sinners' Success

Ryan Coogler Shares Thoughts About Building Community Of Actors Amid 'Sinners' Success -

Heidi Klum Gushes Over Diplo Collab 'Red Eye' Despite DJ Falling Asleep During Video

Heidi Klum Gushes Over Diplo Collab 'Red Eye' Despite DJ Falling Asleep During Video -

Israel Behind Majority Of Journalist Deaths Worldwide, Watchdog Claims

Israel Behind Majority Of Journalist Deaths Worldwide, Watchdog Claims -

'It Would Become A Circus' : Inside Jane's Turmoil For 'little Sister' Fergie Whose Hidden From The World

'It Would Become A Circus' : Inside Jane's Turmoil For 'little Sister' Fergie Whose Hidden From The World -

Inside Cardi B's Real Feelings Related To Stefon Diggs Split Post One Year Of Romance

Inside Cardi B's Real Feelings Related To Stefon Diggs Split Post One Year Of Romance -

Former Sri Lankan Intelligence Chief Arrested Over 2019 Easter Bombings

Former Sri Lankan Intelligence Chief Arrested Over 2019 Easter Bombings -

Kristen Bell Shares One Rule For 'SAG' Awards Ceremony That She Will Ditch This Time: 'Happy And Fun'

Kristen Bell Shares One Rule For 'SAG' Awards Ceremony That She Will Ditch This Time: 'Happy And Fun' -

Woman Suing Meta Platforms, YouTube Over Social Media Addiction Sticks To Claims After Trial

Woman Suing Meta Platforms, YouTube Over Social Media Addiction Sticks To Claims After Trial -

Shakira Applauded For 'gracious' Behaviour By Fans As She Blends Work With Family Downtime

Shakira Applauded For 'gracious' Behaviour By Fans As She Blends Work With Family Downtime -

Mexico’s President Considers Legal Action Over Elon Musk Cartel Remark

Mexico’s President Considers Legal Action Over Elon Musk Cartel Remark -

Prince William Hits The Roof With The Andrew Saga Bleeding Into Earthshot

Prince William Hits The Roof With The Andrew Saga Bleeding Into Earthshot -

HBO Gives Major Update About 'Industry' Season Five And Show's End

HBO Gives Major Update About 'Industry' Season Five And Show's End -

Donnie Wahlberg Responds To 'Boston Blue' Backlash: 'Nobody Was More Disappointed Than Me'

Donnie Wahlberg Responds To 'Boston Blue' Backlash: 'Nobody Was More Disappointed Than Me' -

Jennifer Garner Gets Emotional Over Humble Career Start: 'It Makes Me Want To Cry'

Jennifer Garner Gets Emotional Over Humble Career Start: 'It Makes Me Want To Cry' -

Princess Beatrice Told An Acquaintance That She ‘likes’ Jeffrey Epstein: Grim Verdict Drops

Princess Beatrice Told An Acquaintance That She ‘likes’ Jeffrey Epstein: Grim Verdict Drops -

Late Katherine Short's Neighbours Give Insights Into Her 'peace Loving' Personality Post Suicide

Late Katherine Short's Neighbours Give Insights Into Her 'peace Loving' Personality Post Suicide