Helping athletes or enriching officials?

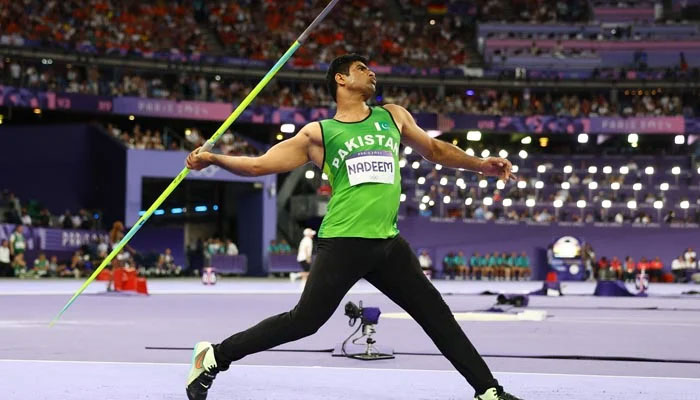

LAHORE: The remarkable success of javelin thrower Arshad Nadeem at the Paris Olympics this year has cast a spotlight on minority sports in Pakistan. More significantly, it underscores a troubling reality that such achievements are often the result of individual dedication rather than support from the country's sporting bodies, including the Pakistan Olympic Association, the Pakistan Sports Board, and the individual federations governing each sport. Arshad's triumph broke a three-decade-long medal drought for Pakistan at the Olympics, with the last medal having been won in 1992.

One would expect that such a breakthrough would prompt these sporting bodies to prioritise nurturing new talent capable of competing at international level. Unfortunately, Pakistan has largely failed to do so. A key reason for this failure lies in the policies of these federations, which seem more focused on preserving the influence of select officials and their allies than on athletes' development.

Take the Pakistan Swimming Federation (PSF) as an example. It recently introduced policies that appear to stifle rather than encourage growth. One such policy requires a player to obtain a No Objection Certificate (NOC) from the federation itself, not from the affiliated unit, before transferring. Additionally, an exorbitant fee of Rs 500,000 must be paid if the transfer occurs before a stipulated three-year period. The registration fee for players has also been hiked, from Rs6,000 to Rs20,000. Such measures seem designed to hinder athletes from advancing in their fields rather than creating pathways for their success.

A swimming federation official claimed while talking to The News that any policy adopted by the PSF is to maintain discipline among the players and maintain a high standard. The governance of these federations further exacerbates the problem. Many are dominated by individuals who wield power not only within the federations but also within specific units, creating a deeply entrenched system of favouritism. In such an environment, players and their families are often left to fight uphill battles against these structures, with no guarantee of success.

A radical overhaul of this system is urgently needed. Players must be allowed the freedom to make choices without discrimination or undue restrictions. No single unit or federation should hold disproportionate power. A competitive environment where talent thrives through merit is essential for fostering excellence in sports.

Importing players from abroad as a stopgap measure does little to address the root problems. Instead, Pakistan must focus on systemic reforms. A thorough assessment of the role and conduct of federations is imperative. The Pakistan Football Federation, for example, has been mired in dysfunction for years, serving as a cautionary tale of what unchecked mismanagement can lead to.

To achieve sustainable progress, Pakistan must widen the base of its sports programmes, encouraging participation from children of all income groups. Federations should empower athletes to make independent decisions about the departments or provinces they represent, free from undue interference.

The focus should shift from consolidating the power of federation officials to enhancing the overall performance of sports in Pakistan. Like other nations, Pakistan must aspire to international success, driven by the talents of its athletes. This requires federations to serve as enablers of growth, not as gatekeepers of power. Only then can Pakistan truly realize its potential on the global sporting stage.

-

Czech Republic Supports Social Media Ban For Under-15

Czech Republic Supports Social Media Ban For Under-15 -

Prince William Ready To End 'shielding' Of ‘disgraced’ Andrew Amid Epstein Scandal

Prince William Ready To End 'shielding' Of ‘disgraced’ Andrew Amid Epstein Scandal -

Chris Hemsworth Hailed By Halle Berry For Sweet Gesture

Chris Hemsworth Hailed By Halle Berry For Sweet Gesture -

Blac Chyna Reveals Her New Approach To Love, Healing After Recent Heartbreak

Blac Chyna Reveals Her New Approach To Love, Healing After Recent Heartbreak -

Royal Family's Approach To Deal With Andrew Finally Revealed

Royal Family's Approach To Deal With Andrew Finally Revealed -

Super Bowl Weekend Deals Blow To 'Melania' Documentary's Box Office

Super Bowl Weekend Deals Blow To 'Melania' Documentary's Box Office -

Meghan Markle Shares Glitzy Clips From Fifteen Percent Pledge Gala

Meghan Markle Shares Glitzy Clips From Fifteen Percent Pledge Gala -

Melissa Jon Hart Explains Rare Reason Behind Not Revisting Old Roles

Melissa Jon Hart Explains Rare Reason Behind Not Revisting Old Roles -

Meghan Markle Eyeing On ‘Queen’ As Ultimate Goal

Meghan Markle Eyeing On ‘Queen’ As Ultimate Goal -

Japan Elects Takaichi As First Woman Prime Minister After Sweeping Vote

Japan Elects Takaichi As First Woman Prime Minister After Sweeping Vote -

Kate Middleton Insists She Would Never Undermine Queen Camilla

Kate Middleton Insists She Would Never Undermine Queen Camilla -

King Charles 'terrified' Andrew's Scandal Will End His Reign

King Charles 'terrified' Andrew's Scandal Will End His Reign -

Winter Olympics 2026: Lindsey Vonn’s Olympic Comeback Ends In Devastating Downhill Crash

Winter Olympics 2026: Lindsey Vonn’s Olympic Comeback Ends In Devastating Downhill Crash -

Adrien Brody Opens Up About His Football Fandom Amid '2026 Super Bowl'

Adrien Brody Opens Up About His Football Fandom Amid '2026 Super Bowl' -

Barbra Streisand's Obsession With Cloning Revealed

Barbra Streisand's Obsession With Cloning Revealed -

What Did Olivia Colman Tell Her Husband About Her Gender?

What Did Olivia Colman Tell Her Husband About Her Gender?