The mighty caste system: Part – I

It seems old beliefs are still dominating millions in India which has one of highest growth rates over decades

Industrial growth and economic development greatly transformed Western societies, bringing structural, political and social changes that helped them get rid of old customs and traditions. The Industrial Revolution led to the abolition of feudalism in the European continent while also drastically reducing the powers of the clergy that had dominated the region for more than 1000 years. In the former Soviet Union, it also wiped out feudalism and helped the giant state get rid of archaic customs and traditions.

Such developments also showed miracles in China where old religious beliefs had been dominating the minds of the people for centuries. Feudal bonds were so strong that nobody could imagine challenging them, let alone fighting and eradicating them. The industrial development in the second-largest economy removed all traces of superstitions and primitive cultures. In addition to that, China, like other modern states, also caught up with the modern world by industrialising itself and getting rid of the old system.

But when it comes to India, it seems that old beliefs are still dominating millions of people in the most populous country of the world which has had one of the highest growth rates over the decades. The most obnoxious remnant of this brutal system is the inhuman caste hierarchy that divides human beings into four layers, each being urged to stick to its designated status. According to this system, the upper caste (Brahmin) is supposed to carry out intellectual works and perform religious duties, the Kshatriyas are born to protect, while the Vaishyas are allotted trading, and the Shudras are condemned to do menial jobs. But that's not the end. Even below this complicated hierarchy is the Dalit or Untouchable – tasked to do inhuman jobs.

Like many Western and industrial states, India has also made tremendous strides in different walks of life; it is considered the hub of global vaccines; its information technology seems to be unmatched in the world; its industrial growth has been impressive since the 1990s; over the past few decades, it has produced some of the richest men in the world; and its Bollywood industry and South Indian cinema are dominating the cultural landscape of the world. The country has witnessed massive urbanisation over the last seven decades and has seen the promotion of education, science and technology.

India has witnessed a phenomenal surge in industrial activities over the decades; in 2022, it had 249,987.000 industrial units. It is a darling of the global capitalist landscape, attracting $667.4 billion of FDI between 2014 and 2024, registering an increase of 119 per cent over the preceding decade (2004-14). This investment inflow spans 31 states and 57 sectors, driving growth across diverse industries.

New Delhi embraced the doctrine of the free market with great zeal during the decade of the 1980s, opening almost all sectors of the economy for 100 per cent FDI – except certain strategically important sectors. FDI equity inflows into the manufacturing sector over the past decade (2014-24) reached $165.1 billion, marking a 69 per cent increase compared to the previous decade (2004 -14), which saw inflows of $97.7 billion.

Nehru’s introverted India also spread its tentacles in the region and beyond. The biggest democracy’s merchandise exports surpassed $437 billion in FY 2023-24. The total employment in the manufacturing sector increased from $57 million in 2017-18 to $64.4 million in 2022-23.

There are conflicting numbers of universities and colleges in India. A 2016-2017 survey says there are 864 universities, 40026 colleges and 11669 Stand Alone Institutions. Out of them, 15 universities are exclusively for women. Recent estimates claim a very high number. Statista claims that as of July last year, India had 5349 universities, the highest number in the world, with 342000 researchers, over 5.4 million IT professionals and over 334 billionaires

But despite all that, the old social hierarchy is still holding sway. Indian leaders championing the cause of 'Shining India' would categorically reject assertions that caste still dominates the Indian social and political landscape but many critics believe it is still prevalent in large swathes of India. This is evident in the way one speaks or dresses. It is visible in one’s skin colour, region and financial income.

There is no reliable data on caste because the last census on it was carried out decades ago. However, Arundhati Roy’s book, 'The Doctor and the Saint', published in 2017, deals with the issue in great detail. According to it, “In the 1931 Census, which was the last to include caste as an aspect of the survey, Vaishyas accounted for 2.7 per cent of the population (while the Untouchables accounted for 12.5 per cent). Given their access to better health care and more secure futures for their children, the figure for Vaishyas is likely to have decreased rather than increased. Either way, their economic clout in the new economy is extraordinary, dominating big businesses, small enterprises, agriculture and industry.” It seems caste and capitalism have blended into a disquieting, uniquely Indian alloy. Cronyism is built into the caste system.

One of the factors contributing to their success lies in religious scriptures. It is believed

Vaishyas are only doing their divinely ordained duty. According to Roy, “The Arthashastra (circa 350 BCE) says usury is the Vaishyas' right. The Manusmriti (circa 150 CE) goes further and suggests a sliding scale of interest rates: 2 per cent per month for Brahmins, 3 per cent for Kshatriyas, 4 per cent for Vaishyas and 5 per cent for Shudras. On an annual basis, the Brahmin was to pay 24 per cent interest and the Shudra and Dalit, 60 per cent. No one can be forced into the service of anyone belonging to a 'lower' caste.”

This does not diminish the importance of Brahmins. She notes that Brahmins were 6.4 per cent of the population according to the 1931 census and their population’s share might have witnessed a downward spiral but their domination is still unshakeable. She notes that they were dominant in the 1940s and their influence is still visible. Quoting Dr Ambedkar, she writes, “According to Ambedkar, Brahmins, who were 3 per cent of the population in the Madras Presidency in 1948, held 37 per cent of the gazetted posts and 43 per cent of the non-gazetted posts in government jobs.”

Quoting figures from senior Indian journalist Khushwant Singh’s article, Roy reveals: “Brahmins form no more than 3.5 per cent of the population of our country, today they hold as much as 70 per cent of government jobs. I presume the figure refers only to gazetted posts. In the senior echelons of the civil service from the rank of deputy secretaries upward, out of 500 there are 310 Brahmins, ie 63 per cent; of the 26 state chief secretaries, 19 are Brahmins; of the 27 governors and Lt-governors, 13 are Brahmins; of the 16 Supreme Court Judges, 9 are Brahmins; of the 330 judges of high courts, 166 are Brahmins; of 140 ambassadors, 58 are Brahmins; of the total 3,300 lAS officers, 2,376 are Brahmins.”

Roy claims that this dominance of the Brahmin is not confined to the bureaucracy but that they also influence politics. “Of the 508 Lok Sabha members, 190 were Brahmins; of 244 in the Rajya Sabha, 89 are Brahmins.” That means 3.5 per cent of the Brahmin community of India holds between 36 per cent and 63 per cent of all plum jobs.

To be continued...

The writer is a freelance journalist who can be reached at: egalitarianism444@gmail.com

-

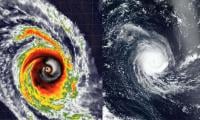

Tropical Cyclone Horacio Becomes World’s First Category 5 Superstorm Of 2026: Latest Forecast & Risks Explained

Tropical Cyclone Horacio Becomes World’s First Category 5 Superstorm Of 2026: Latest Forecast & Risks Explained -

Hilary Duff Recalls Brutal Thing She Did To Husband Matthew Koma After Losing Their Home In Los Angeles Wildfire

Hilary Duff Recalls Brutal Thing She Did To Husband Matthew Koma After Losing Their Home In Los Angeles Wildfire -

Princess Beatrice, Edo Mapelli Mozzi Fall Into Marital Woes: ‘He Doesn’t Want Her Seen With Andrew’

Princess Beatrice, Edo Mapelli Mozzi Fall Into Marital Woes: ‘He Doesn’t Want Her Seen With Andrew’ -

Meta’s Internal Memo Reveals How Executives Ignore Safety Warnings To Push Messenger Encryption Rollout Despite Risks To Teen Safety

Meta’s Internal Memo Reveals How Executives Ignore Safety Warnings To Push Messenger Encryption Rollout Despite Risks To Teen Safety -

Robert Carradine's Shocking Suicide Answer 'lies' In Brother David Old Tragic Incident

Robert Carradine's Shocking Suicide Answer 'lies' In Brother David Old Tragic Incident -

'CIA' Star Tom Ellis Drops Bombshell Reason Why He Stayed Away From 'FBI': I Know What They Do'

'CIA' Star Tom Ellis Drops Bombshell Reason Why He Stayed Away From 'FBI': I Know What They Do' -

Biographer Calls Andrew National Security Risk: ‘This Huge Can Of Worms Is Getting Closer To King’

Biographer Calls Andrew National Security Risk: ‘This Huge Can Of Worms Is Getting Closer To King’ -

DeepSeek Under Fire: Anthropic Accuses Chinese AI Firm Of Misusing Claude For Unauthorized Model Training

DeepSeek Under Fire: Anthropic Accuses Chinese AI Firm Of Misusing Claude For Unauthorized Model Training -

Would You Drive In A Driverless Taxi? AI-powered Robotaxis Roll Out In London Amid Growing Debates Over Road Safety, Passenger Convenience

Would You Drive In A Driverless Taxi? AI-powered Robotaxis Roll Out In London Amid Growing Debates Over Road Safety, Passenger Convenience -

Trump’s Tariff Plan: 10 Percent Rate Takes Effect Despite 15 Percent Announcement Following Supreme Court Ruling

Trump’s Tariff Plan: 10 Percent Rate Takes Effect Despite 15 Percent Announcement Following Supreme Court Ruling -

Eric Church Reveals How Vince Gill Made His Brother Barndon's Death 'a New Normal'

Eric Church Reveals How Vince Gill Made His Brother Barndon's Death 'a New Normal' -

Harry, Meghan Offer Help To Beatrice, Eugenie As They Navigate Big Decision

Harry, Meghan Offer Help To Beatrice, Eugenie As They Navigate Big Decision -

Robert Carradine's Heartbroken Brother Keith Breaks Silence On Actor's Tragic Death

Robert Carradine's Heartbroken Brother Keith Breaks Silence On Actor's Tragic Death -

How Deepfake Scams Are Reaching Record Levels By Targeting Social Media Users: Everything You Need To Know

How Deepfake Scams Are Reaching Record Levels By Targeting Social Media Users: Everything You Need To Know -

Taylor Swift Embraces Herself As Her Career Hits Major Milestone: 'I Am Blown Away'

Taylor Swift Embraces Herself As Her Career Hits Major Milestone: 'I Am Blown Away' -

Andrew’s Arrest Takes Over US Elites: ‘They’re Calling Lawyers In Fear The Police Will Pounce’

Andrew’s Arrest Takes Over US Elites: ‘They’re Calling Lawyers In Fear The Police Will Pounce’