An icon of the left: Part - I

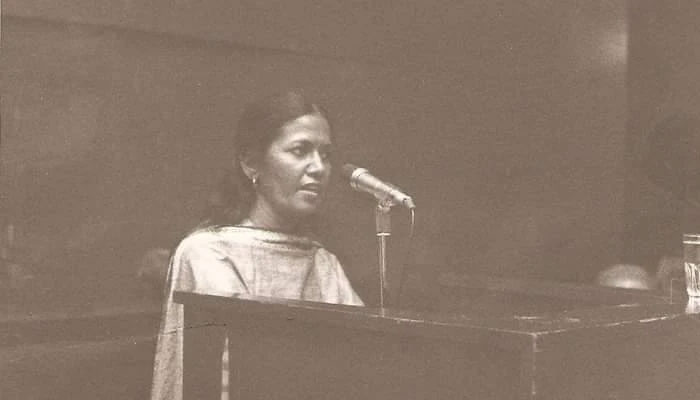

Born in Allahabad in 1943, Saeeda Gazdar migrated to Pakistan after Partition

Those who believe in progressive ideas are leaving us in quick succession. Rahat Saeed – one of the founders of the Irtiqa literary journal and a prominent mobilizer and trade unionist – passed away on October 23. Within two weeks we lost another icon of the leftist politics and progressive movement in Pakistan – Saeeda Gazdar who breathed her last on November 7, 2024.

Born in Allahabad in 1943, she migrated to Pakistan after Partition. She was an outstanding short story writer and a poet of considerable repute belonging to an illustrious family of doctors (both medical and PhD), filmmakers, intellectuals, journalists, and teachers. Her brother Dr M Sarwar (father of Beena Sarwar and husband to Zakia Sarwar) was the shining star of the student movement that the DSF (Democratic Student Federation) led in the early 1950s in Karachi when it was the capital of Pakistan. Saeeda’s husband – Mushtaq Gazdar – was an eminent filmmaker and film historian apart from being an activist and intellectual in his own right.

Saeeda Gazdar’s creative pursuits are reflected in her film scripts, poems, and stories. As editor, she worked with Syed Sibte Hasan – a stalwart of the progressive movement in South Asia. They brought out a literary magazine ‘Pakistani Adab’ in the mid-1970s – unfortunately, only a couple of issues are extant now: one on Amir Khusrau and the other on American writings. She was also a translator of literary pieces from around the world. Her brilliant translation of Bengali writer Shahidullah Kaiser’s novel deserves some comments here. Kaiser was an activist for the democratic and linguistic rights of the people of the former East Pakistan.

In 1952, when the Bengali language movement set off in East Bengal, he became one of the most active members of this struggle and then a few years later he found himself in prison again under the brutal regime of General Ayub Khan. In 1958 while in jail he started writing his novel ‘Sareng Bau’ (The Captain’s Wife, 1962). Interestingly, the same establishment that jailed Kaiser as an allegedly anti-state activist awarded him the Writers’ Guild prize for best novel. Then Kaiser became a victim of forced disappearance during the military action of 1971 in East Pakistan.

Saeeda Gazdar translated this original Bangla novel from English to Urdu and what a marvelous job she did. This is the story of a sailor’s wife who keeps waiting for her husband endlessly and for years keeps her chastity and honour intact only to be accused of adultery when her husband comes back. The novel ends when a gigantic flood destroys their homes and entire villages. Saeeda Gazdar’s translation does full justice to this literary masterpiece of the Bangla language and her diction displays a profound understanding of the tragedies – both natural and manmade – that the people of Bengal endured.

Throughout the 1970s, Saeeda Gazdar kept herself involved in left-wing politics in Karachi and was an active figure in the progressive literary circles. When General Ziaul Haq mounted a military coup against the civilian government of Z A Bhutto, the country found itself under the yoke of an obscurantist regime that was bent upon turning the clock back. General Zia not only violated the constitution and suppressed freedom of expression, but he also arrested thousands of political activists for demanding the restoration of democracy. Journalists received punishments in the form of lashes and incarceration.

That was the time when a majority of the democracy-loving and left-wing activists, journalists and intellectuals were once again at the receiving end of atrocities that the Zia regime was committing, much in the same fashion as Generals Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan had done. Saeeda Gazdar was at the forefront of the democratic struggle in the country and her husband Mushtaq Gazdar was using his own creative talents to expose the dark side of the dictator. Saeeda Gazdar wrote the script for her husband’s 1979 film ‘They are killing the horse’.

The film uses a documentary style to present a fictional account of a young girl with suppressed sexuality. The Gazdars used their creative talents to condemn the treatment that society metes out on women, especially younger ones. It also blends mental illnesses that prevail in Pakistani society on the verge of disintegration. It was a docudrama that won the coveted grand prize at the Tempore International Film Festival in Finland.

The film begins with the girl dreaming of a young man approaching her on a horse while she herself feels like an insect caught in a spider web trying to untangle herself. Thus the script by Saeeda Gazdar sets the tone for a symbolic portrayal of a society that is suppressed, dreams of a saviour on a horseback, and struggles to untangle itself. Then the girl is sitting at the clinic of a psychiatrist who is taking her history. In the flashback we see her travelling by bus to her co-education college where she removes her burka and again hallucinates about that young man, this time around on a motorbike.

She practises telepathy by constantly gazing at the flame of a candle but again in the flame she sees that young man and dreams of her wedding night with him. Back at the clinic, her memories recall a religious procession where a horse is being killed and she collapses because the horse represents her saviour and its killing signifies the shattering of her dreams of liberation. Then the movie takes a more political turn with public floggings under the martial law orders that brutalised Pakistani society to no end. In short, it is a symbolic film of just 30 minutes but conveys its message clearly against the dictatorship.

Throughout this period, Saeeda Gazdar kept writing short stories that highlighted injustices in society, especially under the martial law regime of Gen Zia. Her collection of short stories ‘Aag gulistaan na bani’ (The fire did not turn into a garden) first appeared in 1980. It contains eleven of her short stories mostly dealing with the political and social oppression that the country was going through. The martial-law regime imposed a ban on this book but later under the Junejo government from 1985, it was freely available. Gen Zia was encouraging his own kind of writers who gave a more religious and mystic touch to literature.

Later in 1995, under the second Benazir government, the Pakistan Academy of Letters compiled a special number on Resistance Literature. It selected one of Saeeda Gazdar’s stories in English translation. Just to give a hint about why the book came under proscription, read the following excerpt from the story ‘The cuckoo and the general’. The story begins by describing the lavish lifestyle of a general’s family and their attendance at a school function where the officer is the chief guest. The school staff is delighted to have such an august presence to grace their occasion.

“There was a march-past by the girl students. Left, right. Left, right. Left, left, left. This morning the general had given his approval to the sentences passed on a large number of young men and students belonging to the left. ‘After the third stroke of the whip, thick blood oozes out, just the colour of the red roses placed before you, sir. Strange how such highly coloured blood is present in the weak and emaciated bodies of these people.’ This is how a major had described the scene while giving the general a report after carrying out the sentence.” (translation from Urdu by Tayyaba Akbar Bukhari)

These were the darkest episodes of our history that students do not find in Pakistan Studies books. Saeeda Gazdar penned these incidents and preserved for posterity what could have been lost in a plethora of literature that is highly apolitical.

The writer holds a PhD from the University of Birmingham, UK. He tweets/posts @NaazirMahmood and can be reached at:

mnazir1964@yahoo.co.uk

To be continued

-

King Charles Makes It ‘absolutely Clear’ He Wants To Solve Royal Crisis

King Charles Makes It ‘absolutely Clear’ He Wants To Solve Royal Crisis -

Royal Family Warned To ‘have Answers’ Amid Weak Standing

Royal Family Warned To ‘have Answers’ Amid Weak Standing -

Marc Anthony On Why Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Show Mattered

Marc Anthony On Why Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Show Mattered -

Kid Rock Gets Honest About Bad Bunny’s Performance At Super Bowl

Kid Rock Gets Honest About Bad Bunny’s Performance At Super Bowl -

Kylie Jenner Reveals Real Story Behind Her 'The Moment' Casting

Kylie Jenner Reveals Real Story Behind Her 'The Moment' Casting -

Eva Mendes Reveals One Costar She Envied Ryan Gosling Over

Eva Mendes Reveals One Costar She Envied Ryan Gosling Over -

Halsey Marks Fiancé Avan Jogia's Birthday With Emotional Note

Halsey Marks Fiancé Avan Jogia's Birthday With Emotional Note -

China: Stunning Drone Show Lights Up Night Sky Ahead Of Spring Festival 2026

China: Stunning Drone Show Lights Up Night Sky Ahead Of Spring Festival 2026 -

Andrew's Epstein Scandal: Will King Charles Abdicate Following King Edward's Footsteps?

Andrew's Epstein Scandal: Will King Charles Abdicate Following King Edward's Footsteps? -

Billy Joel Leaves Loved Ones Worried With His 'dangerous' Comeback

Billy Joel Leaves Loved Ones Worried With His 'dangerous' Comeback -

Prince William Dodges Humiliating Question In Saudi Arabia

Prince William Dodges Humiliating Question In Saudi Arabia -

Dax Shepard Describes 'peaceful' Feeling During Near-fatal Crash

Dax Shepard Describes 'peaceful' Feeling During Near-fatal Crash -

Steve Martin Says THIS Film Has His Most Funny Scene

Steve Martin Says THIS Film Has His Most Funny Scene -

Kensington Palace Shares Update As Prince William Continues Saudi Arabia Visit

Kensington Palace Shares Update As Prince William Continues Saudi Arabia Visit -

Fugitive Crypto Scammer Jailed For 20 Years In $73m Global Fraud

Fugitive Crypto Scammer Jailed For 20 Years In $73m Global Fraud -

Will Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor Finally Go To Jail Now That King Charles Has Spoken Out? Expert Answers

Will Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor Finally Go To Jail Now That King Charles Has Spoken Out? Expert Answers