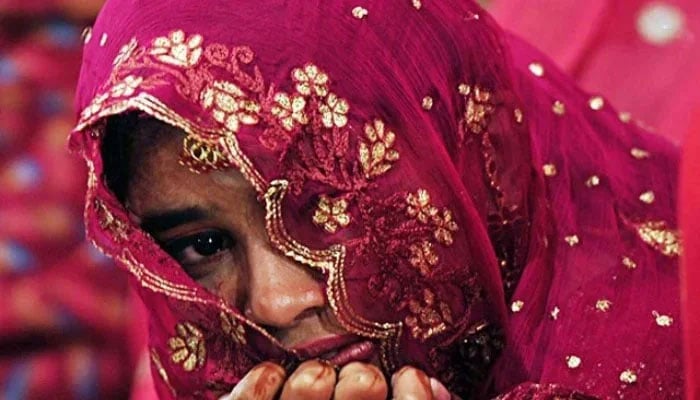

Ending child marriage

Pakistan must revisit history and recognize Quaid-e-Azam’s commitment to eradicating child marriage

There have been numerous attempts by private members of Pakistan’s National Assembly and Senate to amend the country’s Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929. In recent years, the proposed amendments have been repeatedly tabled and rejected. These include the Child Marriage Restraint (Amendment) Bill 2014, moved by MNAs Marvi Memon, Shaista Pervaiz, and the late Pervaiz Malik; a similar bill introduced by Senator Seher Kamran in 2017; and another by Senator Sherry Rehman in 2018. MNA Ramesh Kumar also tabled a related amendment in 2019.

In 2024, Sharmila Faruqui has again introduced a bill aimed at restricting the solemnization of child marriages in the Islamabad Capital Territory. One hopes that in 2024, the political leadership will finally prioritize the welfare of children, particularly girls, and pass the bill with a resounding majority. To achieve this, Pakistan must revisit history and recognize Quaid-e-Azam’s commitment to eradicating child marriage.

Child marriage has been an issue in South Asia long before the independence of Pakistan and India. Despite the criminalization of child marriage under the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929 and the Pakistan Penal Code of 1860, as amended in February 2017, Pakistan still accounts for 28 per cent of the world’s child marriages. Child marriages are often intertwined with another prevalent evil: forced conversions, both of which are in violation of the Fundamental Rights and Principles of Policy enshrined in the constitution of Pakistan.

The continued failure to prioritize criminal provisions against child marriages and enforce protective rights, while operating within a superseding religious-cultural framework, poses a serious threat to Pakistan’s democratic integrity. Child marriages not only undermine rule of law in the country but also lead to violations of international conventions voluntarily signed and ratified by Pakistan, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990 (UNCRC).

The Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929 was a colonial legislative measure introduced to counter cultural norms that supported child marriage and regulate the union under civil law, as opposed to purely religious rites. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, was a vocal advocate for ending child marriage among the Muslim minority in the Central Assembly of India before Pakistan’s creation. He argued for applying a minimum marriage age for Muslim girls, as well as for other religious groups, recognizing the significant impact this issue had.

His stance was met with resistance from the ulema and other Muslim members of the Assembly, who argued that girls who had reached puberty, though under the legal age of majority (18 years), were not victims of child marriage. They believed that once a girl physically matured into a woman, she was ready – and often encouraged – to marry. Revisiting Jinnah’s position on this issue is crucial to understanding where Pakistan’s founder stood on the matter and how the practice of child marriage has evolved in the country since.

Globally, child marriages have been most prevalent in South Asia, where tradition dictated that girls and women were considered financial assets to be disposed of by their male relatives. Access to education, freedom, and independence was nearly non-existent for them. Today, even though women and girls have greater participation in professional and social sectors, why does child marriage still persist in Pakistan?

To understand how other Muslim countries have progressed on this issue, it is essential to examine whether Pakistan faces a unique challenge related to underage marriages. Comparable Muslim-majority countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Iran, Egypt, Turkey, Algeria, and Morocco have all set the legal marriage age at 18. Saudi Arabia, while maintaining a different legal framework, has a Child Protection Law from 2014 that safeguards children under 18 from harm.

Unicef reports that one in four young women in South Asia is married before the age of 18. Child brides are often from low-income households, areas with limited education, and rural regions. Three out of four child brides give birth during adolescence, and they are unlikely to receive formal education. The common denominators in child marriages suggest that poor households resort to marrying off their daughters to reduce the financial burden on the family’s breadwinner. International law recognizes child marriages as a severe violation of human rights, not only affecting the individual but also undermining society at large.

Despite judicial intervention, legislative amendments, and civil society advocacy campaigns, the issue of child marriage continues to plague Pakistani society. Why? One reason is that underage marriages involving Muslim minors often involve forcible conversions. The marriage is considered valid if the girl consents, even though this practice entirely disregards the law’s intent to curtail early marriages. Furthermore, the nikahnama, which requires the consent of adult parties, is rendered meaningless when involving minors. The ineffectiveness of the law stems from misinterpretations and exploitation of loopholes in the statutory text, which does not explicitly declare marriages involving minors void ab initio. In contrast, the law for non-Muslims does not recognize marriages involving minors at all.

In Punjab, the legal age for marriage of girls is still 16, while the Sindh Child Marriages Restraint Act of 2013 defines a ‘child’ as anyone under 18. Following directions from the Lahore High Court, which declared the disparity in marriageable ages for males and females unconstitutional under Article 25, the Child Protection Welfare Bureau has proposed the Child Marriage Restraint Bill 2024-25 to the Punjab government. This bill suggests setting the minimum marriage age at 18 for both genders. It also proposes rigorous penalties, including up to two years of imprisonment and/or fines of up to Rs2 million for adults entering into a marriage contract with a child.

The bill has reportedly been submitted to the chief minister of Punjab and the Punjab Cabinet for consideration. It is hoped that the province will align with other regions in equalizing the minimum marriage age for both genders. However, given the historical and cultural context of this problem, raising awareness in affected communities about the root causes that push families to marry off their young daughters remains crucial.

While women and girls are excelling academically and professionally, and contributing significantly to the labour force, lawmakers continue to hinder social progress due to a lack of political will and insensitivity toward child rights, particularly in marginalized rural areas. The first step in the right direction would be to pass the Child Marriage Restraint (Amendment) Bill without delay.

The writer is a former member of the National Assembly of

Pakistan. She tweets/posts @MehnazAkberAzi

-

Royal Family's Approach To Deal With Andrew Finally Revealed

Royal Family's Approach To Deal With Andrew Finally Revealed -

Super Bowl Weekend Deals Blow To 'Melania' Documentary's Box Office

Super Bowl Weekend Deals Blow To 'Melania' Documentary's Box Office -

Meghan Markle Shares Glitzy Clips From Fifteen Percent Pledge Gala

Meghan Markle Shares Glitzy Clips From Fifteen Percent Pledge Gala -

Melissa Jon Hart Explains Rare Reason Behind Not Revisting Old Roles

Melissa Jon Hart Explains Rare Reason Behind Not Revisting Old Roles -

Meghan Markle Eyeing On ‘Queen’ As Ultimate Goal

Meghan Markle Eyeing On ‘Queen’ As Ultimate Goal -

Japan Elects Takaichi As First Woman Prime Minister After Sweeping Vote

Japan Elects Takaichi As First Woman Prime Minister After Sweeping Vote -

Kate Middleton Insists She Would Never Undermine Queen Camilla

Kate Middleton Insists She Would Never Undermine Queen Camilla -

King Charles 'terrified' Andrew's Scandal Will End His Reign

King Charles 'terrified' Andrew's Scandal Will End His Reign -

Winter Olympics 2026: Lindsey Vonn’s Olympic Comeback Ends In Devastating Downhill Crash

Winter Olympics 2026: Lindsey Vonn’s Olympic Comeback Ends In Devastating Downhill Crash -

Adrien Brody Opens Up About His Football Fandom Amid '2026 Super Bowl'

Adrien Brody Opens Up About His Football Fandom Amid '2026 Super Bowl' -

Barbra Streisand's Obsession With Cloning Revealed

Barbra Streisand's Obsession With Cloning Revealed -

What Did Olivia Colman Tell Her Husband About Her Gender?

What Did Olivia Colman Tell Her Husband About Her Gender? -

'We Were Deceived': Noam Chomsky's Wife Regrets Epstein Association

'We Were Deceived': Noam Chomsky's Wife Regrets Epstein Association -

Patriots' WAGs Slam Cardi B Amid Plans For Super Bowl Party: She Is 'attention-seeker'

Patriots' WAGs Slam Cardi B Amid Plans For Super Bowl Party: She Is 'attention-seeker' -

Martha Stewart On Surviving Rigorous Times Amid Upcoming Memoir Release

Martha Stewart On Surviving Rigorous Times Amid Upcoming Memoir Release -

Prince Harry Seen As Crucial To Monarchy’s Future Amid Andrew, Fergie Scandal

Prince Harry Seen As Crucial To Monarchy’s Future Amid Andrew, Fergie Scandal