Will Afghanistan learn from its past?

Making a flag out of the veil is a perpetual theme of Tappa, a genre of Pashto poetry

A country of stunning natural beauty, Afghanistan is the birthplace of men and women of exceptional brilliance. The Afghan women’s contribution to nation-building is no less than that of Afghan men.

While they upheld their traditional roles as mother, sister, and wife, when compulsions prompted them to step out of their homes, they valiantly defended their country. Making a flag out of the veil is a perpetual theme of Tappa, a genre of Pashto poetry.

Among the galaxies of women in the sky of Afghanistan, two stand head and shoulders above all: Nazo Tokhi and Malala of Maiwand. Tokhi was the mother of Afghan King Mirwais Khan from the Hotak tribe (a sub-tribe of Ghilzai from which Mullah Umar hailed). He drove the Iranians away from Kandahar, leading to the establishment of the Afghan Empire in Persia by his son, Mehmood Khan. Besides being a poet of great literary merit, she fought battles and arbitrated between two warring tribes.

The second woman, Malala of Maiwand, was born 144 years after the death of Nazo Tokhi. Unlike Tokhi who was from a prominent family, Malala was born to a shepherd from the Noorzai tribe (of Hibatulllah Akhunzada, the supreme leader of the Taliban). Her war cry in the battle, ‘My sweet love', is believed to have led to the Afghans’ victory against the British. Her young death at the age of 19 in the Battle of Maiwand on July 27, 1880 carved her a place as the nation’s sweetheart.

Well respected by Afghans, these two women are reverently called Ana, meaning ‘grandmother’. The national anthem of Afghanistan, ‘This is the Home of the Brave’, speaks proudly of Afghanistan’s glorious history and loudly about the invincibility of the Afghans.

Today’s Afghanistan stays in the limelight not due to its stunning natural beauty and great past, shaped by its incredible women and extraordinary men, but due to negative news: denial of education to girls and banning women from the workplace, disdain for diversity, and concerns about sponsoring terrorism, etc.

Having celebrated three years of rule recently, the Afghan Taliban are grappling with myriads of problems, internally and externally. Some issues may not be in their hands, others may not appear on their priority list, and still others may run counter to their ideology. The challenges are enormous.

A few pertinent questions are: will the Afghan Taliban, in a reversal of Afghanistan’s long past, continue to ignore the vibrant Afghan traditions deeply rooted in the country’s history? Are they different from the Taliban of the 1990s, or are they just a repeat of the past? How long will they continue to ignore the nuances of the 21st century? Is holding back 50 per cent of the population out of the mainstream and denying fundamental rights of education to girls beyond the elementary level sustainable in the long run? Will they realize women’s role in post-conflict nation-building? How long will Gen Z Taliban subscribe to the views of the old guard?

Comparing the Afghanistan of 2024 to the Afghanistan of 2000, one would agree with Mark Twain that “History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes”. Despite many similarities between the two regimes, a detached point of view will show that after the August 15 takeover, the Taliban have trodden cautiously.

The cabinet now is relatively more pluralistic (though without a woman), with representation from different ethnic groups, including the Hazara community. The Afghan Taliban’s outlook on sports (for men) is different this time: their leadership’s jubilation over their team’s victories in the ICC Men’s T20 World Cup (played with the old republican flag) was a sharp departure from the previous sports-inimical regime.

Externally, they are more engaging and accessible to international media this time and seem to understand the power of social media. They understand the nuances of diplomacy and international cooperation. They are not as jingoistic as they used to be more than two decades earlier.

Keeping aside the conservative dimension of Afghan society, younger generation Afghans (including young Taliban) are not averse to new ideas. Afghanistan was one of the first Muslim countries to introduce reforms in the early 20s, especially in educational and cultural domains, under King Amanullah and Queen Soraya Tarzi. Denying girls the right to secondary and higher education and banning women from the workplace, a journey too far back in time to regression, is just not tenable.

There has been a growing realization among the Afghan Taliban, especially Gen Z Taliban, that they can’t live in isolation. This realization is reflected in their present policies. Judging from Western perspectives, the Taliban’s governance, democratic ideals, notions of pluralism, and women's rights record may not align with that of the Western world, but from Taliban standards, a tectonic shift is visible. Their earlier radical ideas have metamorphosed into more moderate beliefs, and the Taliban revolution appears to have reached its thermidor.

The exquisite voices of Nazo and Malala Anas cannot be relegated to the dustbin of history. The Taliban may have been successful in winning the guerrilla war, but in the battle of ideas in Afghanistan, which is more than a century old, pragmatism must win.

The writer is a retired ambassador. He can be reached at:

muhammad.tariqcg@gmail.com

-

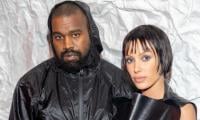

Kanye West's Last Measure To Save Bianca Censori Marriage As He Tries To Salvage Image

Kanye West's Last Measure To Save Bianca Censori Marriage As He Tries To Salvage Image -

Kim Kardashian Finally Takes 'clear Stand' On Meghan Markle, Prince Harry

Kim Kardashian Finally Takes 'clear Stand' On Meghan Markle, Prince Harry -

Christina Applegate Makes Rare Confession About What Inspires Her To Keep Going In Life

Christina Applegate Makes Rare Confession About What Inspires Her To Keep Going In Life -

Patrick J. Adams Shares The Moment That Changed His Life

Patrick J. Adams Shares The Moment That Changed His Life -

Selena Gomez Getting Divorce From Benny Blanco Over His Unhygienic Antics?

Selena Gomez Getting Divorce From Benny Blanco Over His Unhygienic Antics? -

Meet Arvid Lindblad: Here’s Everything To Know About Youngest F1 Driver And New Face Of British Racing

Meet Arvid Lindblad: Here’s Everything To Know About Youngest F1 Driver And New Face Of British Racing -

At Least 30 Dead After Heavy Rains Hit Southeastern Brazil, 39 Missing

At Least 30 Dead After Heavy Rains Hit Southeastern Brazil, 39 Missing -

Courtney Love Recalls How ‘comparison’ Left Marianne Faithfull ‘broken’

Courtney Love Recalls How ‘comparison’ Left Marianne Faithfull ‘broken’ -

Pedro Pascal Confirms Dating Rumors With Luke Evans' Former Boyfriend Rafael Olarra?

Pedro Pascal Confirms Dating Rumors With Luke Evans' Former Boyfriend Rafael Olarra? -

Ghost's Tobias Forge Makes Big Announcement After Concluding 'Skeletour World' Tour

Ghost's Tobias Forge Makes Big Announcement After Concluding 'Skeletour World' Tour -

Katherine Short Became Vocal ‘mental Illness’ Advocate Years Before Death

Katherine Short Became Vocal ‘mental Illness’ Advocate Years Before Death -

SK Hynix Unveils $15 Billion Semiconductor Facility Investment Plan In South Korea

SK Hynix Unveils $15 Billion Semiconductor Facility Investment Plan In South Korea -

Buckingham Palace Shares Major Update After Meghan Markle, Harry Arrived In Jordan

Buckingham Palace Shares Major Update After Meghan Markle, Harry Arrived In Jordan -

Demi Lovato Claims Fans Make Mental Health Struggle Easier

Demi Lovato Claims Fans Make Mental Health Struggle Easier -

King Hospitalized In Spain, Royal Family Confirms

King Hospitalized In Spain, Royal Family Confirms -

Japan Launches AI Robot Monk To Offer Spiritual Guidance

Japan Launches AI Robot Monk To Offer Spiritual Guidance