Pakistan’s struggle for democracy: A nation’s winding path to stability

Over time many European countries established themselves as fully democratic states

Democracy was first adopted in Europe centuries ago and experienced a revival after its decline during the medieval period. Over time, many European countries established themselves as fully democratic states. India, under British colonial rule, faced significant hardships but was also granted important gifts, one of the most notable being democracy. Despite the lack of efforts, resistance, or protest, India was given democratic rights, including voting and constitutional rights under British Raj. While Indians could not choose their rulers during this period, they were introduced to a system where civilians were responsible for electing their leaders.

This democratic system continued in India after independence. However, Pakistan’s journey to democracy was more challenging. Unlike India, Pakistan did not inherit a democratic system from its colonial past. Instead, Pakistan struggled to establish even the most basic forms of democracy and to provide civil rights to its citizens. It took 26 years for Pakistan to develop a constitution that granted proper civil rights.

This delay was not due to a revolutionary struggle but to internal conflicts and discrimination. Early Pakistani parliaments were influenced by racial, religious, and feudal mindsets, prioritising personal interests over the public good. Facing financial difficulties and wartime conditions, Pakistan’s decision-makers were more focused on their own benefits rather than on serving the population. The Objective Resolution’s conservative and extremist ideas reflected this mindset.

The influence of the establishment during Liaquat Ali Khan’s era, particularly from 1951 onwards, was a significant obstacle to Pakistan’s democratic progress. Although Pakistan made impressive strides towards democracy and prepared a final draft of the constitution in 1954, the constituent assembly was dissolved before the implementation of the constitution just because the new constitution was curtailing the power of Governor General Ghulam Mohammad. This setback caused Pakistan to struggle for decades to regain its democratic status.

Several constitutions were drafted over the years, but either Martial law abolished them or they reinforced authoritarian rule, as seen with the 1962 constitution.

Pakistan took excessive time to draft final constitution may be because it was not prime concern of Pakistanis. Discrimination, poverty, corruption, inflation never let the Pakistanis think about democratic rights, they were continuously concerned about security and survival facilities. Whenever martial administrators provided them little facility they didn’t care about rights of other regions who were compromising, e.g. during Ayub times Karachi and Punjab were enjoying while Balochistan and east Pakistan were sacrificing.

Illiteracy and survival concerns contributed to support for dictatorship. However, significant events, such as the Pak-India War, the Asma Jilani Case, and the Bengali riots, pressurised dictators to restore democracy, albeit too late to prevent the country’s breakup into two parts.

Following the separation of Bengal, Pakistan established itself as a democratic state. Yet, the struggle for a true democratic system continued. Even after Bhutto, people celebrated martial law and military rule. Although the military’s official rule ended fifteen years ago, its influence persists. Political parties now govern, but no Prime Minister has completed a full term, and Pakistan continues to grapple with democratic challenges.

Recent shifts in youth attitudes against military luxuries suggest a growing intolerance for dictatorship. Despite this, Pakistan still faces an ongoing struggle to become a fully independent and democratic state.

— The author is a student in the Department of History, University of Karachi

-

Victoria Wood's Battle With Insecurities Exposed After Her Death

Victoria Wood's Battle With Insecurities Exposed After Her Death -

Prince Harry Lands Meghan Markle In Fresh Trouble Amid 'emotional' Distance In Marriage

Prince Harry Lands Meghan Markle In Fresh Trouble Amid 'emotional' Distance In Marriage -

Goldman Sachs’ Top Lawyer Resigns Over Epstein Connections

Goldman Sachs’ Top Lawyer Resigns Over Epstein Connections -

How Kim Kardashian Made Her Psoriasis ‘almost’ Disappear

How Kim Kardashian Made Her Psoriasis ‘almost’ Disappear -

Gemini AI: How Hackers Attempt To Extract And Replicate Model Capabilities With Prompts?

Gemini AI: How Hackers Attempt To Extract And Replicate Model Capabilities With Prompts? -

Palace Reacts To Shocking Reports Of King Charles Funding Andrew’s £12m Settlement

Palace Reacts To Shocking Reports Of King Charles Funding Andrew’s £12m Settlement -

Megan Fox 'horrified' After Ex-Machine Gun Kelly's 'risky Behavior' Comes To Light

Megan Fox 'horrified' After Ex-Machine Gun Kelly's 'risky Behavior' Comes To Light -

Prince William's True Feelings For Sarah Ferguson Exposed Amid Epstein Scandal

Prince William's True Feelings For Sarah Ferguson Exposed Amid Epstein Scandal -

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis -

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign -

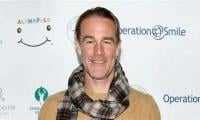

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death -

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s -

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared'

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared' -

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients -

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries -

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting