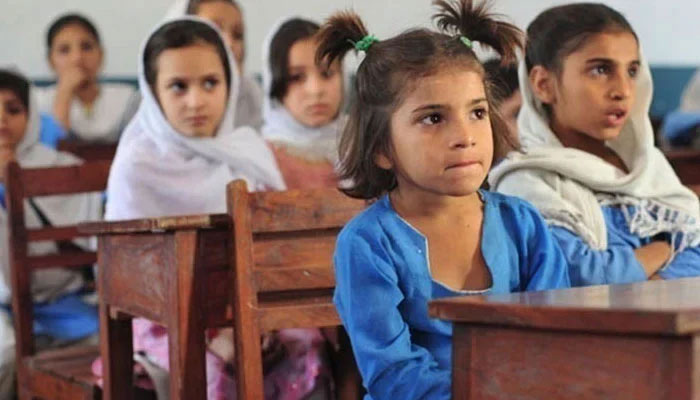

Can Sindh teach its children?

Under Clause 10 of Act, private institutions are required by law to allocate 10% of seats to disadvantaged students

I am at a loss on whether to applaud the Sindh education minister for his current stance or hold him along with his predecessors accountable for neglecting the Sindh Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act 2013 for a decade.

Under Clause 10 of the Act, all private institutions are required by law to allocate 10 per cent of the total seats to disadvantaged students. During his speech on June 25 in the Sindh Assembly, the education minister mentioned this particular clause, seeking support from his colleagues for its implementation.

Since each elected government’s tenure is five years, and luckily the ruling party, the PPP, is currently in its fourth consecutive term, such a state of affairs is appalling, speaking volumes about leaders’ interests in the cause. Lack of implementation has deprived millions of our out-of-school children of availing themselves of this benefit.

Better late than never, the minister has done the right thing by pointing out the lack of implementation of this act. If his colleagues and other stakeholders extend their sincere cooperation in compelling private schools to comply with the law, we will surely witness positive improvements in Sindh’s education indicators.

Having said this, it is not an easy task, considering various ambiguities as well as a lack of a clear mechanism for its implementation. First, it is the government’s constitutional responsibility to ensure free and compulsory education for all children from the primary to secondary levels. How come private schools are forced to shoulder this responsibility? This law is almost a cut-and-paste version of the Indian Education Act, but there are some significant differences worth pointing out here.

First, the Indian Education Act requires 25 per cent admission of disadvantaged students whereas ours stipulates 10 per cent. It is also unclear on what grounds this specific percentage was determined. Besides a difference in percentages, another important thing is that in India, private schools are reimbursed for educating disadvantaged students. On the contrary, in Pakistan, private schools are legally obligated to provide education to such students for free.

This is one of the reasons behind the reluctance of private schools. The situation whould have been much better had the government taken private schools into confidence prior to enacting such legislation. Now, neither is the government able to enforce it effectively nor can private schools openly defy the law. So far, both parties have maintained silence, but how long will this remain unresolved?

The provincial government has also announced its plan to impose a 3.0 per cent sales tax on private schools with annual fee charges exceeding Rs500,000. If implemented, how much revenue will the government gain from this initiative? The total number of registered private schools in the province is 11,736, with a majority being low-cost private schools. Therefore, only a small fraction of elite schools will be subject to this taxation, the burden of which ultimately passes on to the parents.

Given the current status of governance and transparency, such tax measures will bring more public cry than revenue. Hence, all aspects must be carefully weighed before making a decision.

Another area of attention is the eligibility criteria: how to determine who are truly disadvantaged children and how to prioritize them if their number is higher than the available provision of 10 per cent? The task demands meticulous attention to various details pertaining to children: parents’ income, availability of both public and private schools in proximity, social setup, geography, etc.

The Directorate of Inspections and Registration of Private Institutions (DIRPIS), Sindh has formulated a simple criterion involving two categories: deserving children and meritorious students. Deserving children are those who are either orphans or have a single parent, but the term ‘disadvantage’ is quite broad, covering economic, gender, social, geographical, cultural and linguistic aspects. As for meritorious students, those who are academically excellent.

Under this eligibility criteria, the DIRPIS reports that out of the 11,736 private schools, 1,183 schools across six divisions of Sindh (Karachi, Hyderabad, Mirpur Khas, Shaheed Benazirabad, Larkana and Sukkur) have allocated 11.82 per cent of seats to disadvantaged students. While it is pleasing news that they have exceeded the allocated 10 per cent, it is crucial to verify whether these students were genuinely deserving. In this regard, the education minister has appointed 35 inspectors for all divisions; 14 will be posted in Karachi and will start working from August 2024. For transparency, such data should be made public through their website and other platforms.

However, compliance among elite schools is quite low. So far, some of them have given admission to only meritorious students, while deserving ones remain left out. It is observed that most students admitted under the category of meritorious are children of Grade17-18 government officials who somehow managed to secure admission for their children.

Since elite schools not only provide education but also play a role in reproducing and maintaining the dominance of their class in society, they seem reluctant to offer space to disadvantaged children.

Another concern for them seems to be the Education Act that requires that no child or his/her parent be subjected to screening other than academic merit, whereas it is the general practice of such schools to screen both children and parents before admission. Hence, it will be odd for them to waive that practice for disadvantaged students while continuing the same for others. On top of this, integrating disadvantaged students into the elite social milieu will require additional efforts on the part of school(s).

Ten years have gone by, and, another decade might be wasted if implementation challenges are not addressed timely and with prudence and sincerity.

The writer is an education expert

and can be reached at:

asgharsoomro@gmail.com

-

ChatGPT Caricature Prompts Are Going Viral. Here’s List You Must Try

ChatGPT Caricature Prompts Are Going Viral. Here’s List You Must Try -

James Pearce Jr. Arrested In Florida After Alleged Domestic Dispute, Falcons Respond

James Pearce Jr. Arrested In Florida After Alleged Domestic Dispute, Falcons Respond -

Cavaliers Vs Kings: James Harden Shines Late In Cleveland Debut Win

Cavaliers Vs Kings: James Harden Shines Late In Cleveland Debut Win -

2026 Winter Olympics Snowboarding: Su Yiming Wins Bronze And Completes Medal Set

2026 Winter Olympics Snowboarding: Su Yiming Wins Bronze And Completes Medal Set -

Trump Hosts Honduran President Nasry Asfura At Mar-a-Lago To Discuss Trade, Security

Trump Hosts Honduran President Nasry Asfura At Mar-a-Lago To Discuss Trade, Security -

Cuba-Canada Travel Advisory Raises Concerns As Visitor Numbers Decline

Cuba-Canada Travel Advisory Raises Concerns As Visitor Numbers Decline -

Anthropic Buys 'Super Bowl' Ads To Slam OpenAI’s ChatGPT Ad Strategy

Anthropic Buys 'Super Bowl' Ads To Slam OpenAI’s ChatGPT Ad Strategy -

Prevent Cancer With These Simple Lifestyle Changes

Prevent Cancer With These Simple Lifestyle Changes -

Air Canada Flight Diverted St John's With 368 Passengers After Onboard Incident

Air Canada Flight Diverted St John's With 368 Passengers After Onboard Incident -

Experts Reveal Keto Diet As Key To Treating Depression

Experts Reveal Keto Diet As Key To Treating Depression -

Inter Miami Vs Barcelona SC Recap As Messi Shines With Goal And Assist

Inter Miami Vs Barcelona SC Recap As Messi Shines With Goal And Assist -

David Beckham Pays Tribute To Estranged Son Brooklyn Amid Ongoing Family Rift

David Beckham Pays Tribute To Estranged Son Brooklyn Amid Ongoing Family Rift -

Jailton Almeida Speaks Out After UFC Controversy And Short Notice Fight Booking

Jailton Almeida Speaks Out After UFC Controversy And Short Notice Fight Booking -

Extreme Cold Warning Issued As Blizzard Hits Southern Ontario Including Toronto

Extreme Cold Warning Issued As Blizzard Hits Southern Ontario Including Toronto -

Lana Del Rey Announces New Single Co-written With Husband Jeremy Dufrene

Lana Del Rey Announces New Single Co-written With Husband Jeremy Dufrene -

Ukraine-Russia Talks Heat Up As Zelenskyy Warns Of US Pressure Before Elections

Ukraine-Russia Talks Heat Up As Zelenskyy Warns Of US Pressure Before Elections