What is the purpose of a university?

Higher education reforms in Musharraf’s era added ‘research’ as a core activity of Pakistani universities

What is the purpose of a university in the context of Pakistan? Historically, Pakistani universities’ core activities have provided education and produced well-trained graduates, such as engineers and doctors working around the world. Universities have also played a critical role in civic and political movements during the 1940-1970s, such as the independence movement, and produced various political leaders over time.

Higher education reforms in Musharraf’s era added ‘research’ as a core activity of Pakistani universities. The Higher Education Commission (HEC) was set up, which developed indicators, tools, and evaluation criteria to measure research performance. This influenced the hiring, promotion and status of academics and the ranking of Pakistani universities.

The Pakistan Economic Survey of 2023–2024 showed that the number of universities increased from 58 in 2000 to 259 in 2024; 29 universities operate in Islamabad alone. HEC reforms have allowed the public and private sectors to establish universities across Pakistan. Access to higher education has increased from 2.6 per cent in 2002 to 10 per cent in 2024. Similarly, academic articles increased from 641 to over 30,000, and PhD faculty numbers from 800 to 35,000.

Despite these cheerful statistics, Pakistani universities struggle financially; the research lacks depth and recognition; their graduates have lost their quality and impact; and universities have failed to contribute to the country’s socio-economic performance. This is because a core objective of the 2002 Ordinance, which requires HECs to “formulate policies, guiding principles and priorities for higher education institutions for the promotion of socio-economic development of the country” was not emphasized.

We must scrutinize our universities, what and how we teach and conduct research, and how our universities contribute to Pakistan’s success. We must shift from our current practices, as many universities produce students and knowledge that do not help the country’s progress.

The future of higher education in Pakistan is not defined by how many new universities we establish, how many students we produce, and how many papers we publish, but by how these universities contribute to national and provincial development. To create a university that is future-focused, we must revisit the purpose of a university in a rapidly changing world.

Over the next decade, Pakistani universities must work to build capacity that increases the country’s economic productivity, doubles exports, and produces context-specific and socially sensitive knowledge, which will decide the country’s place in the world. This dimension must be achieved by developing clear policies and guidelines at the federal HEC level and embodying them in each provincial HEC and then university-wide strategies. We have to plan teaching and research approaches and invest in infrastructure in our universities according to the national, provincial, and district-level needs and priorities to solve our country’s problems.

I suggest developing national, provincial, and district-level priorities and organizing disciplinary teaching, research, and industry or real-world partnerships. For example, Balochistan will soon become a national and international destination for mining, fisheries and BRI/CPEC education; the northern areas will be the centre of research on climate change and tourism; Punjab and Sindh will become agricultural and food security hubs. Of course, these priorities should be based on the strengths and issues of the area, embracing IT and technological advances such as generative AI, and be carefully thought out. A commitment to the constitution and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals will help develop priorities meeting the expectations of a wider population.

In the proposed model, we must develop a mechanism where universities in one city and district and a province share their teaching and research infrastructure in a collaborative and transparent environment. We can thus promote issue- and solution-based higher education that thinks globally while acting locally to ensure the needs are met. We can assess this model’s success by attracting quality national and international academic staff, students, and funding.

The federal and provincial governments and their HECs will not only play their role as financiers but will also become the partners of the respective governments in their economic, social, and environmental agendas and policies to develop the country’s collective capability. The federal HEC should be empowered to develop country-wide higher education perspectives, policies, and funding to determine what is best for higher education nationally.

They should have coordination and collaboration and quality assurance mechanisms across the country. Higher education in the Netherlands and Finland offer these models of differentiation and collaboration, where long-term planning and a bold national vision, with the support of legislation and policies, achieve better results in national development.

I believe in the autonomy of universities, but this should not come at the cost of unnecessary duplication, low-quality qualifications and research, and insufficient infrastructure. A university should advance knowledge and research that can contribute to the socio-economic development of the country, as promised in the HEC Ordinance over 20 years ago.

We have to extract greater value from our universities by promoting problem/solution-oriented teaching, research, and knowledge in response to the country’s needs. The role of our future universities should be determined by our collective and long-term vision for the country.

The writer is a professor of transport and urban planning at Massey

University, New Zealand.

-

ByteDance’s New AI Video Model ‘Seedance 2.0’ Goes Viral

ByteDance’s New AI Video Model ‘Seedance 2.0’ Goes Viral -

Archaeologists Unearthed Possible Fragments Of Hannibal’s War Elephant In Spain

Archaeologists Unearthed Possible Fragments Of Hannibal’s War Elephant In Spain -

Khloe Kardashian Reveals Why She Slapped Ex Tristan Thompson

Khloe Kardashian Reveals Why She Slapped Ex Tristan Thompson -

‘The Distance’ Song Mastermind, Late Greg Brown Receives Tributes

‘The Distance’ Song Mastermind, Late Greg Brown Receives Tributes -

Taylor Armstrong Walks Back Remarks On Bad Bunny's Super Bowl Show

Taylor Armstrong Walks Back Remarks On Bad Bunny's Super Bowl Show -

James Van Der Beek's Impact Post Death With Bowel Cancer On The Rise

James Van Der Beek's Impact Post Death With Bowel Cancer On The Rise -

Pal Exposes Sarah Ferguson’s Plans For Her New Home, Settling Down And Post-Andrew Life

Pal Exposes Sarah Ferguson’s Plans For Her New Home, Settling Down And Post-Andrew Life -

Blake Lively, Justin Baldoni At Odds With Each Other Over Settlement

Blake Lively, Justin Baldoni At Odds With Each Other Over Settlement -

Thomas Tuchel Set For England Contract Extension Through Euro 2028

Thomas Tuchel Set For England Contract Extension Through Euro 2028 -

South Korea Ex-interior Minister Jailed For 7 Years In Martial Law Case

South Korea Ex-interior Minister Jailed For 7 Years In Martial Law Case -

UK Economy Shows Modest Growth Of 0.1% Amid Ongoing Budget Uncertainty

UK Economy Shows Modest Growth Of 0.1% Amid Ongoing Budget Uncertainty -

James Van Der Beek's Family Received Strong Financial Help From Actor's Fans

James Van Der Beek's Family Received Strong Financial Help From Actor's Fans -

Alfonso Ribeiro Vows To Be James Van Der Beek Daughter Godfather

Alfonso Ribeiro Vows To Be James Van Der Beek Daughter Godfather -

Elon Musk Unveils X Money Beta: ‘Game Changer’ For Digital Payments?

Elon Musk Unveils X Money Beta: ‘Game Changer’ For Digital Payments? -

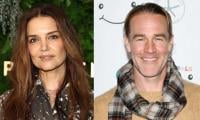

Katie Holmes Reacts To James Van Der Beek's Tragic Death: 'I Mourn This Loss'

Katie Holmes Reacts To James Van Der Beek's Tragic Death: 'I Mourn This Loss' -

Bella Hadid Talks About Suffering From Lyme Disease

Bella Hadid Talks About Suffering From Lyme Disease