Pakistan and the skills report

2024 Global Skills Report report places Pakistan at 84 out of larger cohort of 109 countries in global skills proficiency rankings

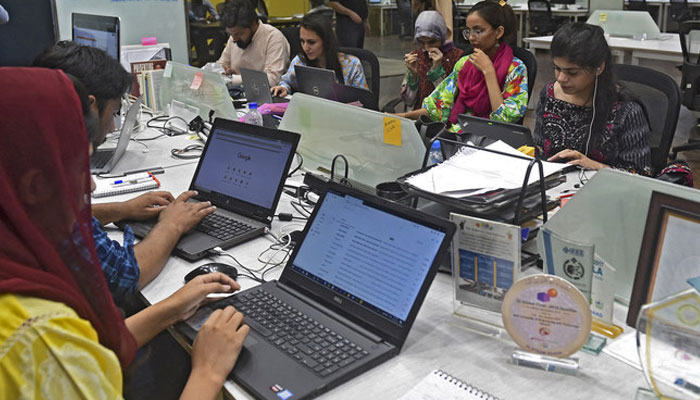

For the last few years, Coursera, the world’s largest provider of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) has been publishing the annual Global Skills Report.

Last year’s report covered 100 countries and placed Pakistan at 92 in its global skills proficiency rankings. It stirred up some excitement here because it covered Pakistan in a few more places than most other included countries (‘Pakistan’s skills report’, July 13, 2023). This year’s report was released a few days ago but is less exciting and more muted for Pakistan watchers. The positive news is that the 2024 report now places Pakistan at 84 out of an even larger cohort of 109 countries in the global skills proficiency rankings (up from 92 out of 100 countries in 2023), surpassing regional neighbours like Oman, India, Bangladesh, etc.

In the Asia-Pacific region, Pakistan placed 15 out of 23 countries. It has been classified as lagging (the lowest of four possible categories), both globally and regionally. The skills rankings are broken down across three areas – business, technology, and data science. One thing that stood out to me is that Pakistan scored modestly higher in business skills and modestly lower in the two other technical skill categories relative to immediate neighbours India and Sri Lanka.

Also, interesting (but unsurprising) is where Pakistan does not appear in the report – in the top-20 list of countries by percentage of labour force who are active learners on the Coursera platform (active learners are defined as learners who have started at least one course in the last year). Most learning materials are free to browse but unless a learner has access to Coursera through a government, employer, or university programme, earning a verifiable certificate requires a subscription usually paid by credit card. That is a significant barrier for many in our country.

That is all the Pakistan-specific information in this year’s report. Beyond that, the report identifies global trends: Learners are pursuing AI and cybersecurity skills globally, the digital skills gap is persisting while the gender gap is narrowing slowly, and broad characterization of differences between types of skills pursued in different regions.

It has been more than a decade since MOOC platforms launched and many commentators, both in the West and here in Pakistan, prognosticated the end of university education. One among several reasons why that did not come to pass is that solutions to tests and assessments of MOOCs are easily available on the internet. Assessment hurdles can be easily cleared by googling for the solutions. That is why MOOCs are great for the genuine learner but the certificates they earn are by themself not trustworthy. For all their imperfections, at least grades earned in traditional university programmes are largely the result of assessments conducted in controlled, supervised settings.

MOOCs are great for the genuine learner but the level of skills they impart can be rather thin. A single MOOC course typically takes about 15-20 hours to work through learning materials and exercises. Compare that with one credit hour of a semester-long university course, which is defined as 16 hours of in-class instruction plus an expectation of at least as many hours of self-study, bringing the total time commitment to about 30 to 40 hours. One university course is usually three credit hours – coming to approximately 120-160 hours of work across a semester. A typical undergraduate degree program comprises at least 130 credit hours: about the equivalent of roughly 250 MOOC courses – you get the idea!

A few targeted MOOCs can be a nice way to round out an education, even a university degree, or quickly bridge a gap in knowledge for a specific task or position but they cannot make up for a good degree programme. However, without putting in many more hours of practice and gaining significant experience, the level of expertise can often be shallow. By themself, MOOCs do not impart the kind of deep and wide expertise that comes from a good degree program (emphasis on good).

Any opportunity that can be secured with a skill that is learnable through a MOOC has a low barrier to entry and is, by extension, just as easily vulnerable to disruption and replacement.

Motivated by the global interest in MOOCs, several Pakistani universities are now exploring offering their own online micro-credential courses. This pursuit is partially motivated by a desire to extend their reach and scale and be seen doing more good and also by the desire to create a new line of revenue with existing resources. The fact that certification courses are not subject to elaborate accreditation processes and do not require keeping the HEC in the loop gives further encouragement to exploring this option.

Of course, the scale will be far from the same as that of Coursera (the largest provider), edX, or any of the other large MOOC providers but the idea is largely the same – to create course materials and automatically graded tests and assignments once that can be recycled year after year with minor updates.

This is not a bandwagon every university ought to jump on. One of the draws of MOOCs is that they allow learners the opportunity to earn a certification from world-renowned institutions or big-tech companies for the price of two or three pizzas. On a side note, this is how people bury their degree qualifications from more ordinary institutions in the education section of their LinkedIn pages under a stack of MOOC certificates from big-name universities (instead of putting them in the certificates section where they belong) and make themselves targets for derision.

Before any university in Pakistan decides to invest resources in developing a portfolio of MOOCs, they need to honestly answer the question, how many learners would choose their MOOCs over those of (literally) the best universities around the world and why? MOOCs offered by our domestic universities could capitalize on the language barrier and start offering their courses in local language(s). However, I see few unique selling points beyond that. This might be an opportunity for the top domestic universities with degree programs that enjoy a reputation for being either very selective or costly.

In conclusion, while the rise of MOOCs offers unprecedented opportunities for learners worldwide, including in Pakistan, the current landscape highlights significant challenges and limitations. Pakistan's gradual improvement in global skills rankings is encouraging, but there remains a considerable gap in proficiency, especially in technical skills. MOOCs, though beneficial for supplementing education and bridging knowledge gaps, cannot replace the depth and rigor of a good university degree program.

For Pakistani universities considering venturing into the MOOC space, it is crucial to recognize the competitive environment dominated by renowned global institutions. The potential success of domestic MOOCs may hinge on unique selling points such as local language offerings and leveraging their reputation within Pakistan. However, without a clear value proposition, these initiatives risk being overshadowed by established international platforms.

Ultimately, the integration of MOOCs into Pakistan's educational framework should be approached with strategic planning and a clear understanding of their role as a complement, rather than a substitute, to comprehensive degree programs. By doing so, we can harness the potential of MOOCs to enhance education, promote lifelong learning, and better prepare our workforce for the evolving demands of the global economy.

The writer (she/her) has a

PhD in Education.

-

Neve Campbell Explains Why She Avoids Watching Scary Movies As She Returns To 'Scream 7'

Neve Campbell Explains Why She Avoids Watching Scary Movies As She Returns To 'Scream 7' -

Milan Tram Crash Leaves Two Dead, 39 Injured

Milan Tram Crash Leaves Two Dead, 39 Injured -

Timothee Chalamet Touches On His Personality's Relatability With 'Marty Supreme' Role

Timothee Chalamet Touches On His Personality's Relatability With 'Marty Supreme' Role -

Benny Blanco Explains Why His Feet Were Dirty During Podcast Debut

Benny Blanco Explains Why His Feet Were Dirty During Podcast Debut -

Jake Humphrey Shares The Powerful Meaning Behind His Wrist Tattoo

Jake Humphrey Shares The Powerful Meaning Behind His Wrist Tattoo -

Matthew Lillard Weighs In On His Return To The 'Scream' Franchise After Decades Of Persistence

Matthew Lillard Weighs In On His Return To The 'Scream' Franchise After Decades Of Persistence -

Travis, Jason Kelce Share Blunt Dating Advice For Men: 'She's Gonna Hate You'

Travis, Jason Kelce Share Blunt Dating Advice For Men: 'She's Gonna Hate You' -

Australia To Launch First High-speed Bullet Train After 50-years Delay

Australia To Launch First High-speed Bullet Train After 50-years Delay -

Meghan Markle Turns To Desperate Bids & Her Kids Are Her ‘saving Grace’: Here’s What They’ll Do

Meghan Markle Turns To Desperate Bids & Her Kids Are Her ‘saving Grace’: Here’s What They’ll Do -

King Charles Gives A Nod To Sister Anne's Latest Royal Visit

King Charles Gives A Nod To Sister Anne's Latest Royal Visit -

Christian Bale Shares Rare Views On Celebrity Culture Urging Fans Not To Meet Him In Person

Christian Bale Shares Rare Views On Celebrity Culture Urging Fans Not To Meet Him In Person -

Ariana Grande To Skip Actor Awards Despite Major Nomination

Ariana Grande To Skip Actor Awards Despite Major Nomination -

North Carolina Teen Accused Of Killing Sister, Injuring Brother In Deadly Attack

North Carolina Teen Accused Of Killing Sister, Injuring Brother In Deadly Attack -

Ryan Gosling Releases Witty 'Project Hail Mary' Ad With Sweet Reference To Eva Mendes

Ryan Gosling Releases Witty 'Project Hail Mary' Ad With Sweet Reference To Eva Mendes -

Teyana Taylor Reveals What Lured Her Back To Music After Earning Fame In Acting Industry

Teyana Taylor Reveals What Lured Her Back To Music After Earning Fame In Acting Industry -

Prince William Shows He's Ready To Lead The Monarchy Amid Andrew Scandal

Prince William Shows He's Ready To Lead The Monarchy Amid Andrew Scandal