Can China’s rise change the world order?

China’s GDP in purchasing power parity terms overtook America’s in 2014

China’s phenomenal rise over the past four decades has radically transformed the global scenario geopolitically and economically, with far-reaching implications for the world’s security and economic wellbeing both at the global and regional levels.

A dispassionate understanding of these developments is a must for Pakistan’s policymakers to be able to safeguard Pakistan’s security and economic interests against the background of the tectonic shifts taking place internationally.

Deng Xiaoping’s programme of market-based economic reforms and opening to the outside world set in motion a process of rapid economic growth averaging 10 per cent per annum for about four decades, enabling it to double its GDP after every seven years.

Consequently, China’s GDP in purchasing power parity terms overtook America’s in 2014. The IMF has forecast that China’s GDP in PPP terms will amount to $35.29 trillion as against $28.78 trillion for the US in 2024. In nominal dollar terms, however, China with its GDP at $18.53 trillion will lag behind America’s $28.75 trillion. But even in nominal dollar terms, China may overtake the American economy in the foreseeable future if it is able to maintain an annual GDP growth rate of 5.0 per cent or above.

China has also achieved remarkable technological growth, especially in quantum computing, semiconductors, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, space exploration, communications, electric vehicles, and solar panels. It is giving a tough time to its competitors in the US and Western Europe in the production of electric vehicles and solar panels, forcing them to impose high tariffs on imports from China to protect domestic industries.

China currently produces about 30 per cent of the world’s manufactured goods and has been the biggest trader in goods in the world since 2013. Its foreign exchange reserves were estimated to be $3.2 trillion in April 2024, the highest level in the comity of nations.

China’s dramatic economic and technological progress has enabled it to build up its military power rapidly over the past three decades. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), China’s military expenditure was estimated to be $296 billion in 2023. It still lagged behind the US which allocated $916 billion for defence in the same year, but according to current projections, China’s military expenditure may catch up with the US within the next two decades.

The rapid rise of China’s economic, technological, and military power has enabled it to pose a potent challenge to the world order, which was established at the end of World War II by the US-led West primarily to maintain its global hegemony and advance its economic and security interests behind the veneer of multilateral institutions such as the UN, World Bank, and IMF.

The fact, however, is that the US and other Western countries themselves have violated the rules of the so-called rules-based order whenever they thought it suited their interests. The US invasion of Iraq in 2003 is an example of such a violation. The US and its allies, in the face of the challenge posed by China, are likely to resist fiercely any attempts to modify the rules defining the existing world order, as they are its main beneficiaries.

The coming decades will, therefore, witness an intense struggle between China and the US-led West as the former pushes for rewriting the rules of the post-World War II world order to accommodate the former’s interests. This struggle would be waged not only in Eurasia but also in Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. As brought home by the conflict in Ukraine, an assertive Russia would be China’s strategic ally in the coming decades in facing Western opposition to the expansion of China’s power and influence at the global and regional levels. The Indo-Pacific region and the Global South would be the main arenas where the 21st century version of the Great Game would be played between the US and China.

It is against this background that the US attempts to contain China by strengthening its alliances with Japan, South Korea, the Philippines and Australia, its strategic partnership with India, and such security groupings as the Quad and AUKUS. The US and its Western allies are also in the process of imposing high tariffs on imports from China to save their domestic industries and prohibiting the export of sensitive technologies to China to slow down its economic progress.

There is currently a bipartisan consensus in the US Congress and its academia on the dire need to resist the worldwide expansion of China’s power and influence. The cover page of the prestigious Foreign Affairs issue for May-June 2024 – which poses the question ‘Can China Remake the World?’ – and the leading articles carried by it reflect the growing American anxiety over China’s dramatic rise. Some of these articles go to the extent of suggesting that the US should not merely manage the emerging cold war with China but win it on the lines of what it did to the Soviet Union.

Thus, the ingredients of Thucydides’s trap, in which the conflict between an existing power and an emerging rival power becomes all but inevitable, are contained in the growing competition for power and influence between the US, the reigning superpower, and China, its main challenger in the 21st century.

Both the US and China and their respective allies are likely to use all the instruments of national power at their disposal, encompassing their political, economic, military, diplomatic and cultural dimensions, in waging this competition. The coming decades will witness growing tensions and localized conflicts in which the two sides would be arrayed against each other directly or through their proxies. However, an all-out nuclear war between them would be avoided because of its likely horrendous consequences.

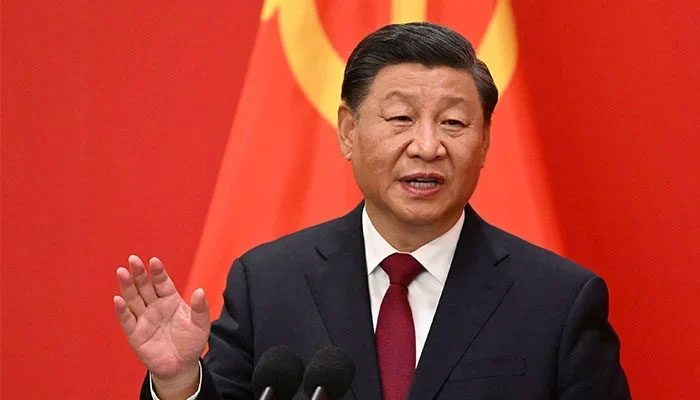

Under President Xi Jinping, China – while strengthening itself economically, technologically and militarily – has taken several initiatives to promote its vision of the emerging global order, encompassing Beijing’s preference for economic development as a foundation for human rights, common security, system diversity and multipolarity.

In pursuance of these goals, President Xi has issued four distinct global programmes including the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, the Global Development Initiative in 2021, the Global Security Initiative in 2022, and the Global Civilization Initiative in May 2023.

Pakistan’s policymakers need to tread carefully in formulating the country’s policies in the face of the emerging new world order which will be characterized by multipolarity, diversity of systems, increasing reliance on power politics, primacy of economic and technological power, and a gradual and long-term dilution of the dominance of the US-led West.

The need for Pakistan to strengthen itself economically, technologically and militarily while pursuing policies of self-reliance and peace in our neighbourhood cannot be overemphasized in such a scenario.

We must also attach the highest importance to the development of our strategic relationship with China while promoting normal friendly relations with Muslim-majority countries, the US-led West, Russia, and prominent countries of the Global South. Finally, we must not lower our guard in the face of the enduring threat posed to our security by India.

The writer is a retired ambassador and author of ‘Pakistan and a World in Disorder – A Grand Strategy for the Twenty-First Century’. He can be reached at: javid.husain@gmail.com

-

New Guest Host Announced For The Kelly Clarkson Show

New Guest Host Announced For The Kelly Clarkson Show -

Why Prince William’s Statement Over Jeffrey Epstein ‘says A Lot’

Why Prince William’s Statement Over Jeffrey Epstein ‘says A Lot’ -

Paul McCrane Reveals Why Playing Jerks Became His Calling Card

Paul McCrane Reveals Why Playing Jerks Became His Calling Card -

Prince William, Kate Middleton Thrashed For Their ‘bland’ Epstein Statement

Prince William, Kate Middleton Thrashed For Their ‘bland’ Epstein Statement -

Bad Bunny Stunned Jennifer Grey So Much She Named Dog After Him

Bad Bunny Stunned Jennifer Grey So Much She Named Dog After Him -

Kim Kardashian's Plans With Lewis Hamilton After Super Bowl Meet-up

Kim Kardashian's Plans With Lewis Hamilton After Super Bowl Meet-up -

Prince William Traumatised By ‘bizarre Image’ Uncle Andrew Has Brought For Royals

Prince William Traumatised By ‘bizarre Image’ Uncle Andrew Has Brought For Royals -

David Thewlis Gets Candid About Remus Lupin Fans In 'Harry Potter'

David Thewlis Gets Candid About Remus Lupin Fans In 'Harry Potter' -

Cardi B And Stefon Diggs Spark Breakup Rumours After Super Bowl LX

Cardi B And Stefon Diggs Spark Breakup Rumours After Super Bowl LX -

Alix Earle And Tom Brady’s Relationship Status Revealed After Cosy Super Bowl 2026 Outing

Alix Earle And Tom Brady’s Relationship Status Revealed After Cosy Super Bowl 2026 Outing -

Why King Charles Has ‘no Choice’ Over Andrew Problem

Why King Charles Has ‘no Choice’ Over Andrew Problem -

Shamed Andrew Wants ‘grand Coffin’ Despite Tainting Nation

Shamed Andrew Wants ‘grand Coffin’ Despite Tainting Nation -

Keke Palmer Reveals How Motherhood Prepared Her For 'The Burbs' Role

Keke Palmer Reveals How Motherhood Prepared Her For 'The Burbs' Role -

King Charles Charms Crowds During Lancashire Tour

King Charles Charms Crowds During Lancashire Tour -

‘Disgraced’ Andrew Still Has Power To Shake King Charles’ Reign: Expert

‘Disgraced’ Andrew Still Has Power To Shake King Charles’ Reign: Expert -

Why Prince William Ground Breaking Saudi Tour Is Important

Why Prince William Ground Breaking Saudi Tour Is Important