How democracy was derailed — Part – III

As we saw in the previous article in this series (April 28), between the Tamizuddin judgment and the advice rendered under Special Reference No 1, the federal court led by Justice Munir had effectively dismantled the constitutional structure of Pakistan.

Not only that but coupled with the Justice Munir Judgment earlier in the Umar Khan case in the Punjab High Court, the foundation had been laid for nondemocratic, extra-constitutional governance for decades to come. In the Umar Khan case, Munir upheld the conviction of a civilian in a military court. In so doing, he ignored the age-old dictum that civilians could not be tried in a military court unless civilian courts had ceased to function.

To support his judgment, he relied upon British court judgments from history where such verdicts were upheld in situations where the conquering British army was suppressing rebellions in Ireland and South Africa. He used these judgments against a conquered people and applied them to the citizens of his own independent country.

The new assembly constituted by Ghulam Muhammad drafted a constitution that was approved by the governor-general in April 1956. The key elements of the constitution were: one unit with parity between East and West Pakistan, despite the eastern part having a bigger population (approximately 56 per cent); a high degree of provincial autonomy; joint electorate; a parliamentary form of government but with almost unfettered powers for the president.

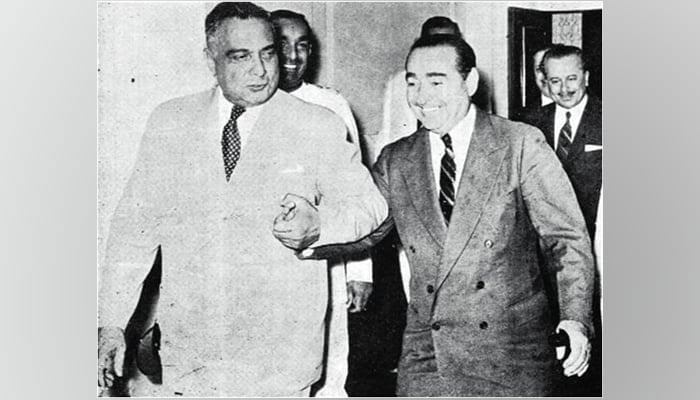

Soon after the constitution was adopted, the health of Ghulam Muhammad took a turn for the worse and in August, Maj Gen (honorary) Iskander Mirza took over as president of Pakistan. From 1947 to 1954, Iskander Mirza had been defence secretary before becoming governor of Bengal. Soon after Mirza became governor, the newly elected Bengal assembly and government were dissolved, and he ran the province as an executive governor.

Soon after taking over, Mirza removed Bogra as prime minister and appointed Chaudhary Mohammad Ali in his place. In just over two years that Iskander Mirza was president, there were four different prime ministers appointed by him. Chaudhary Mohammad Ali, Husain Shaheed Suhrawardy, I I Chundrigar and Malik Feroz Noon followed each other in quick succession. An argument given in favour of the imposition of martial law in 1958 was political instability and rapid change of prime ministers, showing that politicians could not hold the country together let alone progress with so much political division.

However, history says otherwise. In the first six years of the country's existence when power was in the hands of the politicians, there was only one change of prime minister, and that too was necessitated by the assassination of PM Liaqat Ali Khan. In the next five years, with power being exercised by the non-elected governor-general, backed by the military and the judiciary, there were five different prime ministers.

On October 7, 1958 Iskander Mirza – perhaps tired of having to put up even the pretence of democracy – declared martial law. The central and provincial assemblies were dissolved, and the government of Feroz Noon was sacked. There was at that time a case concerning a murder charge against a resident of Pishin, Balochistan named Dosso. This case implied that the high court had held in favour of Dosso and found the FCR under which Dosso had been convicted to be in violation of the 1956 constitution. That called into question the martial law imposed by Iskander Mirza and the validity of the laws (continuance in force order, 1958) promulgated after the imposition of martial law.

Once again, the Munir-led federal court came to the rescue of the president for this blatantly extra-constitutional step. He stated in his judgment: “Thus a victorious revolution or a successful coup is an internationally recognized legal method of changing a constitution. After a change of the character I have mentioned has taken place, the national legal order must for its validity, depend upon the new law-creating organ. Even courts lose their existing jurisdiction and can function only to the extent and in the manner determined by the new constitution.”

In other words, he was saying that those who controlled the coercive powers of the state had the right to suspend the constitution whenever they so desired, for as long as they desired, and their word would be law and binding on both the citizens and the courts.

The judgment in the Dosso case was delivered on December 27, 1958. With the carte blanche provided to the coercive powers of the state by the Dosso judgment, it came as no surprise that the next day General Ayub Khan deposed Iskander Mirza and became president and chief martial law administrator.

With this takeover, the pendulum of power decisively shifted from the civil servants to the military. Martial law continued to be in place for 13 years, albeit with a change at the top with Yahya Khan replacing Ayub Khan in 1968. The will of the people was again denied after the 1970 elections, this time ending with the tragic separation of East Pakistan from the western side in 1971 aided by an invading Indian army.

In the first 11 years after the creation of the country and until the 1958 martial law of Ayub Khan, three Bengali prime ministers – Nazimuddin, Bogra, and Suhrawardy – were dismissed. However, some political representation continued to be there from Bengal with one faction or the other of the Bengali political leadership having a share in power. With the dismissal of Iskander Mirza as president (Mirza was from Bengal), and a completely West Pakistani-led army taking direct charge, any vestiges of Bengali share in the power structure of the country evaporated in all but name.

The 1954 elected provincial assembly and the Fazlul Haq cabinet were dissolved after just two months in office, despite having won more than 90 per cent of the Muslim seats. In the 1970 elections, the Awami League led by Sheikh Mujib won 160 out of 162 seats in East Pakistan. The PPP, having won only 81 seats, all in West Pakistan, was the second largest party. Despite this massive mandate, power was not transferred to the Awami League.

The message to the Bengalis was the same as that to the rest of the country: the will of the people does not matter and will not be respected. Separated by a thousand miles of hostile territory and shut out from the corridors of power, the people of Bengal came to the conclusion that the only way to exercise power would be to separate from the West.

This was the disastrous consequence of trying to run a multi-ethnic country like Pakistan with reliance only on coercive power. Pakistan with its genesis in a democratic constitutional struggle led by the great Quaid-e-Azam, can only prosper as a true constitutional democracy where the will of the people is supreme.

Seventy-five years of history show that all attempts to do otherwise have failed – and will continue to fail. The choice is in our hands. For the sake of the 250 million people of this land, we hope that we will learn from history and not continue to repeat the failures of the past. Unfortunately, the signs are not auspicious.

Concluded

The writer is a retired corporate CEO and former federal minister.

-

Mexico’s President Considers Legal Action Over Elon Musk Cartel Remark

Mexico’s President Considers Legal Action Over Elon Musk Cartel Remark -

Prince William Hits The Roof With The Andrew Saga Bleeding Into Earthshot

Prince William Hits The Roof With The Andrew Saga Bleeding Into Earthshot -

HBO Gives Major Update About 'Industry' Season Five And Show's End

HBO Gives Major Update About 'Industry' Season Five And Show's End -

Donnie Wahlberg Responds To 'Boston Blue' Backlash: 'Nobody Was More Disappointed Than Me'

Donnie Wahlberg Responds To 'Boston Blue' Backlash: 'Nobody Was More Disappointed Than Me' -

Jennifer Garner Gets Emotional Over Humble Career Start: 'It Makes Me Want To Cry'

Jennifer Garner Gets Emotional Over Humble Career Start: 'It Makes Me Want To Cry' -

Princess Beatrice Told An Acquaintance That She ‘likes’ Jeffrey Epstein: Grim Verdict Drops

Princess Beatrice Told An Acquaintance That She ‘likes’ Jeffrey Epstein: Grim Verdict Drops -

Late Katherine Short's Neighbours Give Insights Into Her 'peace Loving' Personality Post Suicide

Late Katherine Short's Neighbours Give Insights Into Her 'peace Loving' Personality Post Suicide -

Fresh Details Of King Charles, Queen Camilla's US Visit Emerge Amid Andrew Investigation

Fresh Details Of King Charles, Queen Camilla's US Visit Emerge Amid Andrew Investigation -

Iran 'set To Buy' Chinese Carrier-killer Missiles As US Forces Gather In Region

Iran 'set To Buy' Chinese Carrier-killer Missiles As US Forces Gather In Region -

Prince Harry And Meghan Unlikely To Meet Royals In Jordan

Prince Harry And Meghan Unlikely To Meet Royals In Jordan -

Hero Fiennes Tiffin Shares Life-changing Advice He Received From Henry Cavill

Hero Fiennes Tiffin Shares Life-changing Advice He Received From Henry Cavill -

Savannah Guthrie's Fans Receive Disappointing News

Savannah Guthrie's Fans Receive Disappointing News -

Prince William Steps Out For First Solo Outing After Andrew's Arrest

Prince William Steps Out For First Solo Outing After Andrew's Arrest -

Jake Paul Chooses Silence As Van Damme Once Again Challenges Him To Fight

Jake Paul Chooses Silence As Van Damme Once Again Challenges Him To Fight -

Google Disrupts Chinese-linked Hacking Groups Behind Global Cyber Attacks

Google Disrupts Chinese-linked Hacking Groups Behind Global Cyber Attacks -

Four People Killed In Stabbing Rampage At Washington Home

Four People Killed In Stabbing Rampage At Washington Home