How democracy was derailed — Part – I

It is said that those who do not learn from the mistakes of the past are bound to repeat them. In the case of Pakistan, the huge mistakes that were made in our first decade of existence, and the disastrous consequences that ensued, seem to have been forgotten.

As Pakistan continues to struggle with the task of running a sustainable constitutional democracy, it's worth looking back in history to see what went wrong and who played a part in those decisions which derailed democracy. The only chance we had of keeping a country united, which was divided by geography, language and cultural traditions, was lost as we tore apart the constitutional democratic roots of the nation.

Another aspect of this early history that is extremely important to revisit is the role of the nonpolitical institutions of the state structure – judiciary, civil bureaucracy and military – in this derailment of democracy and the consequent separation of the two wings of the country.

Very often in the last few decades, we have heard of the interests of the state being supreme. However, no state that does not hold the interests of the people of the country as supreme has any meaning. The separation of state interests from the interests of the people of the nation is a recipe for disaster and bound to fail. The finest arbiters of state interests are the people who make up the nation and no self-appointed guardian of state interests can be wiser than the judgment of the people who comprise the nation. In the words of the great Urdu poet Ibrahim Zoq, “Zubane khalq ko naqqarae khuda samjho”

Pakistan started its life with a constituent assembly that was tasked with the dual role of carrying out federal legislation and finalizing the first constitution of Pakistan. The roots of the constituent assembly were in the 1946 elections which formed the basis for the creation of Pakistan. Therefore, Pakistan started its existence with a strong democratic foundation.

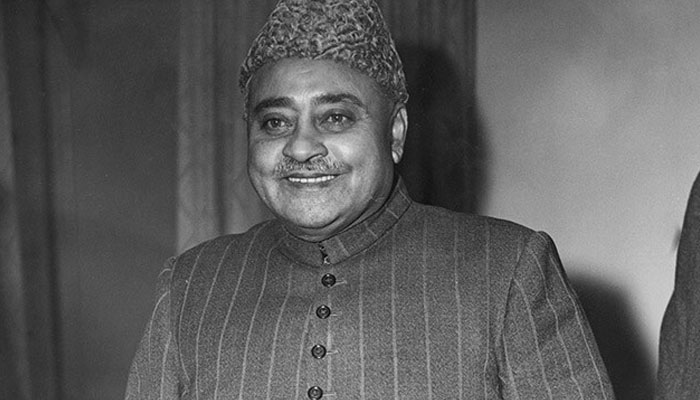

Until the time that Liaquat Ali Khan was prime minister, the democratic structure continued to be in place. Unfortunately, Liaqat Ali Khan was murdered in October 1951. After his demise, Khwaja Nazimuddin became the prime minister and Ghulam Mohammad, a career civil servant, became the governor-general. It was in this post-Liaquat Ali Khan era that the derailment of democracy and power slipping out of the hands of the political leadership and into the hands of the non-elected segments of the state started.

In March 1949, the constituent assembly passed the Objectives Resolution which set out the guiding principles of the constitution and set up a Basic Principles Committee which was tasked to formulate the key issues to be dealt with in the constitution. The most vital of these issues were: 1) the relationship between the center and provinces and the power balance between the two wings of the country; and 2) the role of Islam in the laws of the nation and its governance.

The first report of the Basic Principles Committee was laid in front of the Constituent Assembly on Dec 22, 1952. However, it faced a lot of criticism from different segments of society. After the Punjab Muslim League which had earlier supported the report withdrew its support, the report was withdrawn on Jan 21, 1953 for further consideration.

Soon after that, riots erupted in Lahore demanding that Ahmadis be declared non-Muslim. To restore order, martial law was imposed in Lahore on March 6. The situation was brought under control but on April 17 Ghulam Muhammad dismissed prime minister Khwaja Nazimuddin and his cabinet. The derailment of democracy in Pakistan had started.

There was nothing in the law that authorized the governor-general to dismiss the PM. Khwaja Nazimuddin pointed this out to Ghulam Muhammad when the latter asked him to resign. However, Nazimuddin did not put up any public resistance to this unconstitutional step. He stated that it was important that nothing be done that might weaken Pakistan domestically or embarrass it internationally. Nazimuddin was replaced by Muhammad Ali Bogra, who like Nazimuddin was a Bengali. In addition to having served in the Suhrawardy cabinet of pre-partition Bengal, he had served twice as Pakistan’s ambassador to the US.

Work on the Basic Principles Report continued under Bogra. In September when the constituent assembly reconvened, the work on the constitution took center stage. On October 7, Bogra reintroduced the Basic Principles report with two amendments from the previous draft. Earlier, the assembly had overwhelmingly rejected the draft put together by Ghulam Muhammad which was designed to concentrate powers in the hands of the governor-general particularly the power to dissolve the constituent assembly. The amended draft of the Basic Principles report was approved by the cabinet, the provincial chief ministers, and the Muslim League parliamentary party. This paved the way for the much-awaited constitutional approval from the constituent assembly.

The Constituent Assembly started a clause-by-clause reading and approval of the approximately 250 clauses of the constitution. They reached an agreement on 130 clauses including the most important issues of the Islamic character of the state and the federal structure. The remaining clauses were those on which an agreement was expected to be easy to reach. The assembly was prorogued mid-November after working nonstop for nearly two months. Provincial assembly elections were to take place in Bengal in March and attention then turned towards these elections.

Four opposition parties in Bengal formed a ‘United Front’ to contest this election. The results were absolutely stunning and resulted in a humiliating loss for the Muslim League. Of the 237 Muslim seats, 223 were won by the parties of the United Front and 143 by Suhrawardy’s Awami League.

Fazlul Haq’s Krishak Sramik party won 48. The Muslim League was only able to win nine seats. Even Nazimuddin lost his seat. The United Front formed a government with Fazlul Haq as chief minister – the same Fazlul Haq who had introduced the Lahore Resolution (now called Pakistan Resolution) in 1940, which became the one-point election manifesto for the 1946 referendum and resulted in the creation of Pakistan.

Just two months after Fazlul Haq had taken oath as CM, Section 92A was invoked and the East Pakistan Assembly was dissolved. Major-Gen (r) Iskander Mirza was appointed governor of East Pakistan and the centre took direct control of the province. This was a disastrous decision in so many ways. A government that had won 94 per cent of all Muslim seats just two months back and had the overwhelming support of the people of Bengal had been dismissed by a stroke of the pen.

Fazlul Haq, the mover of the Pakistan resolution and a man called a tiger by Quaid-e-Azam, had been sent packing after Khwaja Nazimuddin the leading Bengali Muslim Leaguer had already been dismissed as PM the previous year. Last but not least, East Pakistan was now to be controlled directly from West Pakistan, separated from the east by a thousand miles of hostile Indian territory. The will of the people had been crushed under the bureaucratic hammer – and the derailment of democracy was accelerating.

To be continued

The writer is a retired corporate CEO and former federal minister.

-

Jonathan Majors Set To Make Explosive Comeback To Acting After 2023 Conviction

Jonathan Majors Set To Make Explosive Comeback To Acting After 2023 Conviction -

Next James Bond: Why Jacob Elordi May Never Get 007 Role?

Next James Bond: Why Jacob Elordi May Never Get 007 Role? -

Maddox Drops Pitt From Surname In Credits Of Angelina Jolie’s New Film 'Couture' Despite Truce From Father's End In Legal Battle

Maddox Drops Pitt From Surname In Credits Of Angelina Jolie’s New Film 'Couture' Despite Truce From Father's End In Legal Battle -

Burger King Launches AI Chatbot To Track Employee Politeness

Burger King Launches AI Chatbot To Track Employee Politeness -

Andrew’s Woes Amid King Charles’ Cancer Battle Triggers Harry Into Action For ‘stiff Upper Lip’ Type Dad

Andrew’s Woes Amid King Charles’ Cancer Battle Triggers Harry Into Action For ‘stiff Upper Lip’ Type Dad -

Experts Warn Andrew’s Legal Troubles In UK Could Be Far From Over

Experts Warn Andrew’s Legal Troubles In UK Could Be Far From Over -

Teyana Taylor Reflects On Dreams Turning Into Reality Amid Major Score

Teyana Taylor Reflects On Dreams Turning Into Reality Amid Major Score -

Jennifer Garner Drops Parenting Truth Bomb On Teens With Kylie Kelce: 'They're Amazing'

Jennifer Garner Drops Parenting Truth Bomb On Teens With Kylie Kelce: 'They're Amazing' -

AI Is Creating More Security Problems Than It Solves, Report Warns

AI Is Creating More Security Problems Than It Solves, Report Warns -

'Game Of Thrones' Prequel 'A Knight Of The Seven Kingdoms' New Ratings Mark Huge Milestone

'Game Of Thrones' Prequel 'A Knight Of The Seven Kingdoms' New Ratings Mark Huge Milestone -

Apple Seeks To Dismiss Fraud Suit Over Siri AI, Epic Injunction

Apple Seeks To Dismiss Fraud Suit Over Siri AI, Epic Injunction -

Delroy Lindo Explains The Crucial Role Of Musical Arts In Setting Up His Career Trajectory

Delroy Lindo Explains The Crucial Role Of Musical Arts In Setting Up His Career Trajectory -

Timothée Chalamet Reveals How He Manages To Choose The Best Roles For Himself

Timothée Chalamet Reveals How He Manages To Choose The Best Roles For Himself -

Princesses Beatrice, Eugenie’s Conflict Gets Exposed As Mom Fergie Takes Over The Media

Princesses Beatrice, Eugenie’s Conflict Gets Exposed As Mom Fergie Takes Over The Media -

Kate Middleton Plays Rock-paper-scissors In The Rain

Kate Middleton Plays Rock-paper-scissors In The Rain -

Lindsay Lohan On 'confusing' Teen Fame After 'Mean Girls': 'I Should Have Listened To My Mom And Dad'

Lindsay Lohan On 'confusing' Teen Fame After 'Mean Girls': 'I Should Have Listened To My Mom And Dad'