Forgotten cinema

Unfortunately, Pakistani films and TV dramas have seldom ventured beyond domestic intrigues and love triangles

The World Bank has sounded the alarm on the ‘historic reversal’ of development for poor countries. Nearly half of the world’s least-developed countries are experiencing a widening income gap with the wealthiest economies, for the first time since the turn of the century.

The concentration of wealth in the hands of a few rich people has been a consistent feature in most countries around the world. The list of the 14 richest people whose net worth is more than $100 billion is interesting, featuring 10 Americans and one each from France, India, Mexico and Spain. Their collective wealth is nearly $2,000 billion, enough to eradicate extreme poverty and illiteracy around the globe.

The same applies to wealth concentration in countries like India and Pakistan. Call it ‘elite capture’ if you will, India and Pakistan are two of the worst examples of economic and social injustices. Though India has at least some achievements to show the world and has become one of the largest economies, this is just one side of the picture.

Pakistan is even worse as its economy has shrunk, growth lingered, population increased, poverty expanded, and education lagged. The ‘elite’ that comprises big business owners, feudal lords, industrialists, and civil and military bureaucracy appears to be least interested in doing something concrete to modify an inherently unjust system.

The plight of the poor is not a new phenomenon. Just read the works of Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy to understand what poverty looked like in Great Britain. Similarly, the short stories by Chekov, Gorky, Maupassant, and Premchand are great to understand the economic imbalance in France, India and Russia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

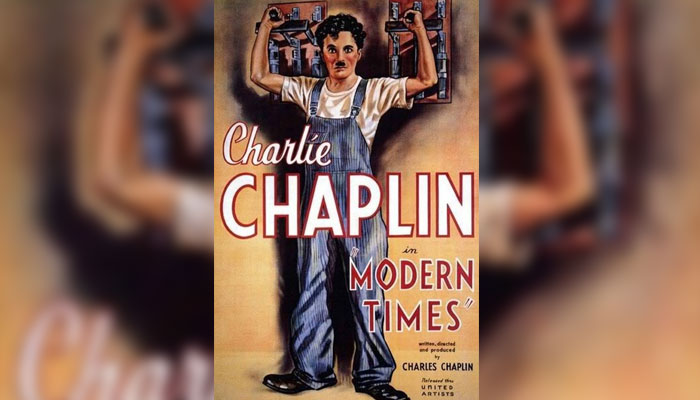

Here I would like to recommend two silent movies from nearly a century ago: German masterpiece ‘Metropolis’ (1927) and Charlie Chaplin’s ‘Modern Times’ (1936). Both serve as an indictment of an increasingly capitalist and industrialized world that treated its ordinary citizens as the ‘wretched of the earth’, to borrow from Frantz Fanon.

‘Metropolis’ is a more demanding film experience than ‘Modern Times’ which blends entertainment while educating its viewers in a characteristic Chaplin style. Both are silent cinema classics and have drawn admiration and respect from audiences for decades.

If you like watching movies and are more interested in educating yourself than in sheer entertainment, start with ‘Metropolis’. The enjoyment aspect you can cover while watching ‘Modern Times’. There was a time when we used to hunt for such movies, but now it is much easier through online streaming – you can watch movies anywhere, anytime.

The theme of these movies is industrialization and mass production in early 20th-century Europe and America. Though both have graduated from industrial to post-industrial and information-based economies, fundamental contradictions in society remain the same, revolving around wealth concentration in a few hands.

‘Metropolis’ is more futuristic and based on science fiction, portraying humanity’s struggle against science and technology and the compulsive urge in some people to use them for exploitative purposes. Both films reveal workers as the cogs tied to the city’s machinery.

Austrian director Fritz Lang and British actor and director Charlie Chaplin both shared a vision of a grim society and used some of the most impressive images in film history. For example, the opening shots of both films are similar. Lang shows depressed and haggard workers slowly entering a factory located under the city of ‘Metropolis’.

Chaplin uses a similar sequence with a more hilarious impact by substituting workers with a herd of sheep that follow each other in a bustling city. Both cities have two distinct classes: industrialists with ample resources and workers enduring a bare-bones existence of backbreaking work.

The story of ‘Metropolis’ also concerns forbidden love between a young man from the industrial class and a girl who is an activist preaching against the class divide. There is also an element of deceit involving a robot duplicate of the girl, culminating in a revolution with a disaster of sorts. It has a clear message to fight against injustices. But the film was called communist propaganda. Later, the same thing happened to ‘Modern Times’. Years later, both appear on the list of the greatest films ever made.

While ‘Metropolis’ blends graphics and hand-drawn animation that appear seamless, ‘Modern Times’ is a milestone for its visual impact. Fritz Lang and Charlie Chaplin drew their inspiration from America’s skyscrapers they saw as structures where people worked as slaves for the good of the dominant elite.

In ‘Metropolis’, a capitalist and a scientist use the face of the activist girl to superimpose on a human machine that brings chaos to the world of workers. In the end, the workers unite and destroy both the robot and the scientist while the industrialist mends his ways and begins respecting the workers.

Charlie Chaplin launched ‘Modern Times’ nearly a decade after Lang’s movie, which was released before the Great Depression. By 1936, the economic depression had had its devastating impact on American society, and there were repeated dust storms in the country, culminating in the Dust Bowl of the late 1930s that John Steinbeck so skilfully documented in his novel ‘The Grapes of Wrath’, which was adapted for film in 1940. That was the time when the clouds of another major war were hovering over the world and the military industry was thriving while people were toiling just to make a living.

‘Modern Times’ was farsighted for its time, as it showed the struggle of people to renounce alienation from their work and preserve humanity in a mechanized world. Karl Marx used the concept of alienation to expose the process in which workers feel foreign to the products of their labour. This is as meaningful today as it ever was. ‘Modern Times’ was perhaps the last great silent film, but it spoke volumes about the tramp in a derby hat who experienced the economic and political consequences of the Great Depression.

In the 1930s, most young men had no choice but to leave their farms to work in factories, but after gruelling work on the assembly line, they usually had nervous breakdowns. How true this is even today, especially for countries such as India and Pakistan.

In ‘Modern Times’, the worker goes through the process of institutionalization, but after his treatment and release, he accidentally picks up a red flag – prompting authorities to consider him a communist agitator. He goes to jail, successfully escapes, and falls in love with a young girl running from the police after stealing a loaf of bread. They evade the police and keep struggling for a better life.

Luckless workers find themselves unnerved by attempting to cope with the equipment and machinery they operate. The breakdown that we see almost every day in the cities and towns of Pakistan is the result of the same alienation and exploitation that Chaplin and Lang showed in their movies.

Unfortunately, Pakistani films and TV dramas have seldom ventured beyond domestic intrigues and love triangles. That is one reason I recommend watching good movies of yore to enhance our understanding of the complexities of modern life – to learn some lessons about how the gap between the rich and the poor has been affecting people’s lives and how creative artists have contributed to exposing injustices in society.

The writer holds a PhD from the University of Birmingham, UK. He tweets/posts @NaazirMahmood and can be reached at:mnazir1964@yahoo.co.uk

-

Lana Del Rey Announces New Single Co-written With Husband Jeremy Dufrene

Lana Del Rey Announces New Single Co-written With Husband Jeremy Dufrene -

Ukraine-Russia Talks Heat Up As Zelenskyy Warns Of US Pressure Before Elections

Ukraine-Russia Talks Heat Up As Zelenskyy Warns Of US Pressure Before Elections -

Lil Nas X Spotted Buying Used Refrigerator After Backlash Over Nude Public Meltdown

Lil Nas X Spotted Buying Used Refrigerator After Backlash Over Nude Public Meltdown -

Caleb McLaughlin Shares His Resume For This Major Role

Caleb McLaughlin Shares His Resume For This Major Role -

King Charles Carries With ‘dignity’ As Andrew Lets Down

King Charles Carries With ‘dignity’ As Andrew Lets Down -

Brooklyn Beckham Covers Up More Tattoos Linked To His Family Amid Rift

Brooklyn Beckham Covers Up More Tattoos Linked To His Family Amid Rift -

Shamed Andrew Agreed To ‘go Quietly’ If King Protects Daughters

Shamed Andrew Agreed To ‘go Quietly’ If King Protects Daughters -

Candace Cameron Bure Says She’s Supporting Lori Loughlin After Separation From Mossimo Giannulli

Candace Cameron Bure Says She’s Supporting Lori Loughlin After Separation From Mossimo Giannulli -

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Are ‘not Innocent’ In Epstein Drama

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Are ‘not Innocent’ In Epstein Drama -

Reese Witherspoon Goes 'boss' Mode On 'Legally Blonde' Prequel

Reese Witherspoon Goes 'boss' Mode On 'Legally Blonde' Prequel -

Chris Hemsworth And Elsa Pataky Open Up About Raising Their Three Children In Australia

Chris Hemsworth And Elsa Pataky Open Up About Raising Their Three Children In Australia -

Record Set Straight On King Charles’ Reason For Financially Supporting Andrew And Not Harry

Record Set Straight On King Charles’ Reason For Financially Supporting Andrew And Not Harry -

Michael Douglas Breaks Silence On Jack Nicholson's Constant Teasing

Michael Douglas Breaks Silence On Jack Nicholson's Constant Teasing -

How Prince Edward Was ‘bullied’ By Brother Andrew Mountbatten Windsor

How Prince Edward Was ‘bullied’ By Brother Andrew Mountbatten Windsor -

'Kryptonite' Singer Brad Arnold Loses Battle With Cancer

'Kryptonite' Singer Brad Arnold Loses Battle With Cancer -

Gabourey Sidibe Gets Candid About Balancing Motherhood And Career

Gabourey Sidibe Gets Candid About Balancing Motherhood And Career