Moral suasion isn’t the answer

Whenever the economy is up the creek, as at present, messages start doing the rounds that if each Pakistani shuns foreign products and buys only locally made goods for at least a few months, it will set the stage for putting the economy back on track.

Preference for domestic over imported products, the argument goes, is a sure recipe for cutting back on imports, saving valuable foreign exchange, driving up the local currency, and putting life back into the domestic industry. As a result, the nation will not have to dance to the tune of hard-nosed foreign creditors.

The logical question is: how can we cut down on imports? This can be done in two ways. One, the government may restrict imports through administrative measures ranging from imposing high customs duties to clamping outright prohibitions on imports. Being in charge of a sovereign state, the Pakistani government can resort to such a remedy without much ado. In fact, this remedy seems so obvious that the man in the street and pseudo-economists alike cannot help wondering what is holding back the people calling the shots from waving the magic wand.

Be that as it may, given the country’s commitments arising out of legally binding international treaties and protocols, only a narrow policy space is available to the government to scale down imports. Besides, the restrictive measures may force our trading partners to retaliate by subjecting our exports to similar treatment. The result will be a zero-sum game. That is one reason that efforts to substantially curtail imports through punitive measures normally come a cropper.

While the government may have its hands tied by the compulsions of international law and the niceties of diplomatic norms, the same does not apply to the people. In the end, every industrial buyer and final consumer is the judge of where to procure from. So if they decide to purchase only domestically made goods, no one can force their hand to do otherwise. Thus, on the face of it, the argument to stop buying foreign goods makes a lot of sense. But then why do we each year spend billions of dollars on foreign goods? Are we short on patriotism? Are we too xenocentric to reject foreign goods? Or do we have the incorrigible habit of cutting our own throats?

The answer is that buying foreign or local products is not a question of patriotism or xenocentrism or, for that matter, of having irrepressible collective suicidal tendencies; instead, it’s simply a matter of satisfying consumer needs and wants. Imports represent the difference between domestic demand and domestic output (minus exports); the wider the gap, the higher the import volume. All else equal, high imports are undergirded by low productive capacity relative to domestic demand.

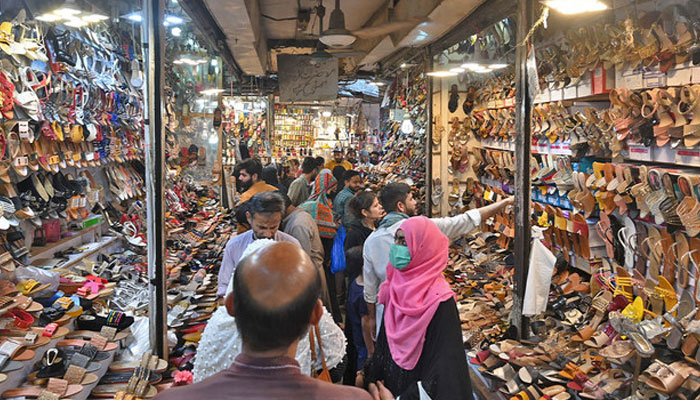

Pakistan has a rather narrow production or manufacturing base. We are essentially a producer of primary products, such as wheat, cotton, sugarcane, and rice, and low value-added manufactures, such as textiles and leather articles, and processed food that are derived from these primary products. A wide range of the products that our households and factories use are either not manufactured locally at all or are produced on a scale too small to meet the demand.

Such products include fossil fuels, chemicals and fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, iron and steel, machinery and electronic equipment, vehicles, consumer durables, and aircraft. In case the manufacturing concerns or households insist on buying only homemade or locally grown products out of sheer patriotism, the resulting scenario is not difficult to construct.

Our homes and factories, schools and hospitals, will be without electricity, as well as other facilities deemed essential for decent living or working conditions. Automobiles will not be plying on the roads -- it may be noted in passing that despite having one of the most heavily protected automobile industries in the world, we are only an assembler of vehicles – and offices will have to work without the necessary equipment. There will be no internet, no social or electronic media -- not even newspapers, as newsprint is imported. In a word, we will be thrown at least a century back.

Domestic supply-side constraints are well brought out by the import profile. During the last financial year (FY2022-23), the import bill amounted to $55 billion, which included $17 billion in petroleum products, $11 billion in machinery and appliances, $9 billion in chemicals and pharmaceuticals, $6.5 billion in metals, $1.8 billion in vehicles and auto parts, and $3 billion in raw materials. The cumulative size of these products comes to $48.3 billion, which accounts for nearly 88 per cent of the total imports. The import of these goods is essential for running our offices and factories and expanding the economy.

Even in industries where we have sufficient productive capacity, the efficiency of the production processes and the quality of products are below the mark. Customers, whether they are households or industrial users, want the best value for their hard-earned money. While making purchase decisions, they are guided by the utility maximization rule: buying within their budget constraints that basket of goods and services that will afford them the highest possible satisfaction.

While ‘satisfaction’ is subjective and each buyer may look for different product characteristics, consumer behaviour is not all that arbitrary. While shopping, customers have some expectations of manufacturers or suppliers in terms of product reliability, performance, safety, conformity to standards, and after-sales service. No one expects their new refrigerator to go kaput when the mercury rises. When fulfilled, the expectations create brand loyalty. The principal reason for the preference for foreign brands is that few local brands command customer loyalty.

Despite being an agricultural economy -- agriculture accounts for some one-fifth of the GDP -- Pakistan is a net food importer. In FY2022-2023, our net food imports (the difference between food exports and imports) exceeded $5 billion. Of these, palm oil had the largest share ($3.6 billion), followed by wheat ($01 billion), pulses ($946 million) and tea ($569 million). The consumption of tea and pulses is part of our culture, while palm oil is used in processed fruit.

Pakistan does not produce palm oil, while only a limited amount of tea is grown in the country. Likewise, pulses are cultivated on less than 5.0 per cent of the total crop area. Together with rice, they constitute the staple food for the vast majority of households. The output of wheat, one of our major crops, keeps oscillating between surplus and deficit.

Likewise, despite being the world’s fourth largest cotton producer, Pakistan imports cotton, partly because of shrinking cotton output and partly because the local produce is not deemed of ‘export quality.’ In FY2022-2023, raw cotton valued at $1.7 billion was imported.

Because of the nation’s heavy dependence on foreign products, import restrictions almost always end up putting the brakes on economic growth, with all their adverse implications in terms of job creation and revenue generation. Hence, using moral suasion to cut back on imports and promote made-in-Pakistan goods, however momentarily appealing this may be to eyes and ears, is not the answer.

How many of us will ride an unreliable cab, just because it is owned by the neighbour next door, while appearing for a job interview? It is only by shoring up the productive capacity of the economy and developing credible local brands that dependence on foreign products can be shed.

Moral suasion does have relevance to efforts for economic revival. It can be used to discourage conspicuous consumption and wasteful expenditure, a chunk of which is accounted for by imports, promote the economy of resource (such as water) utilization, and encourage people to pay taxes. However, the efficacy of the moral argument in such cases is anybody’s guess.

The writer is an Islamabad-based columnist. He tweets @hussainhzaidi and can be reached at: hussainhzaidi@gmail.com

-

Leonardo DiCaprio's Co-star Reflects On His Viral Moment At Golden Globes

Leonardo DiCaprio's Co-star Reflects On His Viral Moment At Golden Globes -

SpaceX Pivots From Mars Plans To Prioritize 2027 Moon Landing

SpaceX Pivots From Mars Plans To Prioritize 2027 Moon Landing -

J. Cole Brings Back Old-school CD Sales For 'The Fall-Off' Release

J. Cole Brings Back Old-school CD Sales For 'The Fall-Off' Release -

King Charles Still Cares About Meghan Markle

King Charles Still Cares About Meghan Markle -

GTA 6 Built By Hand, Street By Street, Rockstar Confirms Ahead Of Launch

GTA 6 Built By Hand, Street By Street, Rockstar Confirms Ahead Of Launch -

Funeral Home Owner Sentenced To 40 Years For Selling Corpses, Faking Ashes

Funeral Home Owner Sentenced To 40 Years For Selling Corpses, Faking Ashes -

Why Is Thor Portrayed Differently In Marvel Movies?

Why Is Thor Portrayed Differently In Marvel Movies? -

Dutch Seismologist Hints At 'surprise’ Quake In Coming Days

Dutch Seismologist Hints At 'surprise’ Quake In Coming Days -

Australia’s Liberal-National Coalition Reunites After Brief Split Over Hate Laws

Australia’s Liberal-National Coalition Reunites After Brief Split Over Hate Laws -

DC Director Gives Hopeful Message As Questions Raised Over 'Blue Beetle's Future

DC Director Gives Hopeful Message As Questions Raised Over 'Blue Beetle's Future -

King Charles New Plans For Andrew In Norfolk Exposed

King Charles New Plans For Andrew In Norfolk Exposed -

What You Need To Know About Ischemic Stroke

What You Need To Know About Ischemic Stroke -

Shocking Reason Behind Type 2 Diabetes Revealed By Scientists

Shocking Reason Behind Type 2 Diabetes Revealed By Scientists -

SpaceX Cleared For NASA Crew-12 Launch After Falcon 9 Review

SpaceX Cleared For NASA Crew-12 Launch After Falcon 9 Review -

Meghan Markle Gives Old Hollywood Vibes In New Photos At Glitzy Event

Meghan Markle Gives Old Hollywood Vibes In New Photos At Glitzy Event -

Simple 'finger Test' Unveils Lung Cancer Diagnosis

Simple 'finger Test' Unveils Lung Cancer Diagnosis