The meaning of democracy

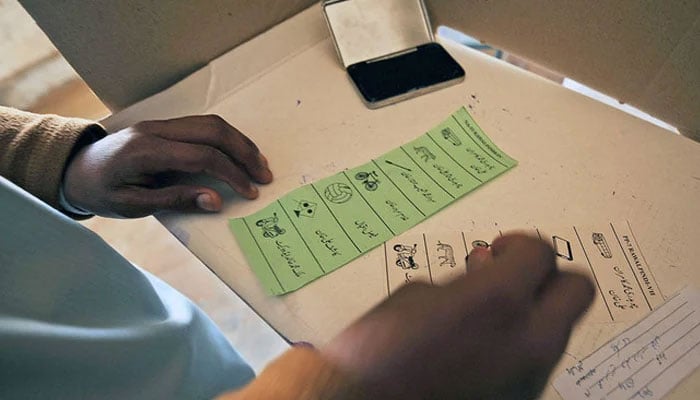

There are many perceived problems with the most recent exercise in polling carried out in Pakistan

Democracy is the system of government that most analysts in the country and beyond it believe may be the best for our future. The question however is how it is put in place. There are many perceived problems with the most recent exercise in polling carried out in Pakistan which have left many disillusioned with the system and unwilling to accept its outcome.

This is hardly surprising given the reports we are seeing of valid return forms which seem to have been quite clumsily tampered with and results would seem on the surface at least extremely strange given that initial readings from various polling stations within a constituency did not match the outcome. The same errors made in previous polls when the number of ballots cast for national and provincial assembly elections carried out on the same day did not match are also beginning to emerge. We do not know what will happen as election tribunals consider the various pleas placed before them but we do know that this would be a long process that may not yield results for many weeks, many months, or even longer.

Chief Election Commissioner Sikandar Sultan Raja had promised in past interviews before the polls that he would step down if there was any doubt about the transparency and fairness of the 2024 elections. Like others before him, he has reneged on these pledges.

The result is that there is now little faith left in the Election Commission of Pakistan as a body, and people are even less willing than before to trust the voting process and the question of what happens to the votes they cast. If these have no meaning, then our democracy itself has very little value in the eyes of people. It can in other words be said to have left behind a nation whose distrust in democracy grows by the day. In time, this will mean even lower turnouts and even less interest in polls since people know how they can be managed.

The new leaders who have come to power, including Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, need to be questioned about why he suggested unelected institutions be granted a supervisory role in the polling process rather than leaving the conduct and counting of ballots up to the government officials appointed for this purpose.

In India, the democratic process itself has only rarely come under any kind of question or any shadow. We need to try and understand why this is the case. Of course, the fact that the Indian armed forces have never taken hold of the country or attempted to do so by force is one reason for this. There also are other reasons entrenched in a more stable and more practiced process of democracy.

If doubts continue to pour in, as is happening in the present time, questions will arise over whether these elections can stand and hold their rest of time. If they cannot, we have to ask what happens next and what this would mean for the country already badly injured by a history of unfair play and problems at polling stations during past elections. We have to find a way to end this lack of transparency and the many doubts that seem to come with each election, as has been the case since the initial exercise of democracy carried out in 1970. The lack of fair play can only injure all the political parties and, unfortunately, they lack the ability to step forward, talk and sort things out amongst themselves.

The issue is not only to amend the system but also to build people's faith in democracy. This cannot happen if there is so much doubt about how the outcome was reached and by whom. The polling process itself needs to be far more open to scrutiny and far more transparent in the manner in which it is conducted. This is being said not only of the 2024 results but also of that in 2018 and the balloting for nationwide elections carried out in the years before this.

In 2018 we are told that from the room where the final result was compiled, the agents of political parties were not allowed entry as should be the case under the law and instead locked out by giant doors on which bolts and locks had been placed. This is extremely unfortunate and the manner of tampering has become more and more evident to people over the past few years as they have become better educated in the methods and nuances of democracy.

We need to iron out the sheet and make sure a clean one is laid out. It is probably not possible to do this immediately. But the question raised at the 2024 poll and the debate in which the media was allowed to look and question many aspects of it holds out some hope for the future. Of course, not all was as transparent and as visible as it should be. But we can only hope that by moving forward, people will become better versed in what to look for and how to judge if a fair verdict has been reached. If the outcome of the election is not fair, a question arises on why this expensive exercise should be conducted at all and what purpose it then serves.

These are key questions in any system where polling by the people stands as a key part of bringing a new government to power. The questions being raised over the allocation of reserved seats add to the whole equation. We need to put in place a body that can correctly oversee elections and their outcome as is the case for the most part in neighbouring countries. We also need to understand why some countries succeed in holding polls that are perceived as fair and others do not. Very grave questions over the polling process have been raised even in the US. We need to move beyond these issues and tell people quite what happened and why.

The reports now coming forward from organizations such as Pildat, Fafen and HRCP, raise some of the blinds. But still more transparency is needed if we need people to have faith in the process itself and if they are to be expected to cast their votes for candidates who they believe can lead the country out of its current crisis.

The writer is a freelance columnist and former newspaper editor. She can be reached at:

kamilahyat@hotmail.com

-

Pistons Vs Hornets Recap: Brawl Erupts With 4 Players Getting Tossed Before Detroit Victory

Pistons Vs Hornets Recap: Brawl Erupts With 4 Players Getting Tossed Before Detroit Victory -

Gordie Howe Bridge Faces Uncertainty After Trump Warning To Canada

Gordie Howe Bridge Faces Uncertainty After Trump Warning To Canada -

Air Canada’s Flights To Cuba Halted As As Aviation Fuel Crisis Worsens

Air Canada’s Flights To Cuba Halted As As Aviation Fuel Crisis Worsens -

Marc Anthony Weighs In On Beckham Family Rift

Marc Anthony Weighs In On Beckham Family Rift -

New Guest Host Announced For The Kelly Clarkson Show

New Guest Host Announced For The Kelly Clarkson Show -

Why Prince William’s Statement Over Jeffrey Epstein ‘says A Lot’

Why Prince William’s Statement Over Jeffrey Epstein ‘says A Lot’ -

Paul McCrane Reveals Why Playing Jerks Became His Calling Card

Paul McCrane Reveals Why Playing Jerks Became His Calling Card -

Prince William, Kate Middleton Thrashed For Their ‘bland’ Epstein Statement

Prince William, Kate Middleton Thrashed For Their ‘bland’ Epstein Statement -

Bad Bunny Stunned Jennifer Grey So Much She Named Dog After Him

Bad Bunny Stunned Jennifer Grey So Much She Named Dog After Him -

Kim Kardashian's Plans With Lewis Hamilton After Super Bowl Meet-up

Kim Kardashian's Plans With Lewis Hamilton After Super Bowl Meet-up -

Prince William Traumatised By ‘bizarre Image’ Uncle Andrew Has Brought For Royals

Prince William Traumatised By ‘bizarre Image’ Uncle Andrew Has Brought For Royals -

David Thewlis Gets Candid About Remus Lupin Fans In 'Harry Potter'

David Thewlis Gets Candid About Remus Lupin Fans In 'Harry Potter' -

Cardi B And Stefon Diggs Spark Breakup Rumours After Super Bowl LX

Cardi B And Stefon Diggs Spark Breakup Rumours After Super Bowl LX -

Alix Earle And Tom Brady’s Relationship Status Revealed After Cosy Super Bowl 2026 Outing

Alix Earle And Tom Brady’s Relationship Status Revealed After Cosy Super Bowl 2026 Outing -

Why King Charles Has ‘no Choice’ Over Andrew Problem

Why King Charles Has ‘no Choice’ Over Andrew Problem -

Shamed Andrew Wants ‘grand Coffin’ Despite Tainting Nation

Shamed Andrew Wants ‘grand Coffin’ Despite Tainting Nation