Language matters

Around 40% of world’s people lack this opportunity with figure reaching an estimated 90% in certain regions

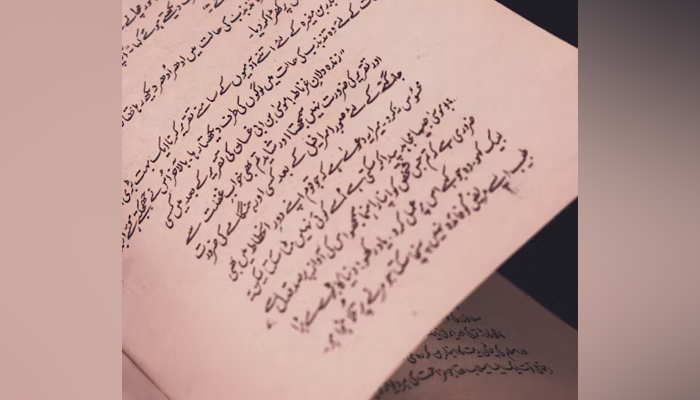

International Mother Language Day, proclaimed by Unesco in 1999, is observed annually on February 21 to promote linguistic and cultural diversity, with this year’s theme focusing on multilingual education as a pillar of learning and, in particular, intergenerational learning. Research shows that children, or even adult learners, learn best when taught in their native language. And yet, around 40 per cent of the world’s people lack this opportunity, with the figure reaching an estimated 90 per cent in certain regions. This is due in large part to the fact that of the approximately 7000 languages thought to be spoken in the world today, only a few hundred hold an official place in education systems and the public domain. Less than a hundred are in use in the digital domain, meaning more people will be excluded from learning in the language in which they can learn best as education begins to shift towards the digital realm. Even more alarmingly, an estimated 45 per cent of all languages thought to be spoken today are classified by the UN as endangered, with around one language going extinct every fortnight.

This is a sign of widespread linguistic and cultural majoritarianism, with profound implications for both equity and overall development. For starters, those lucky enough to have their language officially used in education, business and law have a distinct advantage over those not so lucky. At least one Swedish study shows that being taught in English leads to significantly worse learning outcomes and dropout rates when it is not a student’s first language. In Pakistan’s case, the fact that out of the over 70 different languages reported to be spoken in the country only two, English and Urdu, have full official recognition can be directly tied to our abysmal development indicators. While much of the concern about education in Pakistan is, understandably, directed towards the over 28 million children who are not in school, there is evidence that even many of the children in school are not learning anything. Early Grade Reading Assessment tests conducted in 2013 found that most students, from all four provinces, could not fully read a 60-word passage in Urdu. Even those who could had little comprehension of what they were reading and were not able to answer most questions about the passage.

What these test results show is that, for all the time and ink spent on the Urdu-English debate, many are unwilling or unable to understand that, in practice, a greater insistence on Urdu would be just as exclusionary for most Pakistani children. Critics of the neo-colonial preference for English in Pakistani schools, white-collar jobs and ‘polite society’ are right to point out that those who struggle with English are unfairly dismissed as unintelligent or uneducated. However, it would be just as unfair to similarly dismiss a Pashto, Punjabi, Sindhi or Balochi speaker for not knowing Urdu. It is thus not surprising that many, if not most, Pakistanis end up outside official education and employment, locked out of an Anglo-Urdu bubble that is far smaller than most can fathom. Sadly, the attempts made at tackling the education-language crisis would only widen existing gaps if implemented. The Pakistani dream is often to leave Pakistan, with the people arguably the country’s most successful export via remittances. Producing more Pakistanis with better English undoubtedly helps with this. However, if it is eventually decided that Pakistan is worth salvaging and the country’s growth and development should come from within, embracing the country for what it is and not narrow conceptions of what it ought to be would be a good place to start. This is a multilingual and multicultural country and for it to move forward, this must be reflected in its official languages.

-

All You Need To Know Guide To Rosacea

All You Need To Know Guide To Rosacea -

Princess Diana's Brother 'handed Over' Althorp House To Marion And Her Family

Princess Diana's Brother 'handed Over' Althorp House To Marion And Her Family -

Trump Mobile T1 Phone Resurfaces With New Specs, Higher Price

Trump Mobile T1 Phone Resurfaces With New Specs, Higher Price -

Factory Explosion In North China Leaves Eight Dead

Factory Explosion In North China Leaves Eight Dead -

Blac Chyna Opens Up About Her Kids: ‘Disturb Their Inner Child'

Blac Chyna Opens Up About Her Kids: ‘Disturb Their Inner Child' -

Winter Olympics 2026: Milan Protestors Rally Against The Games As Environmentally, Economically ‘unsustainable’

Winter Olympics 2026: Milan Protestors Rally Against The Games As Environmentally, Economically ‘unsustainable’ -

How Long Is The Super Bowl? Average Game Time And Halftime Show Explained

How Long Is The Super Bowl? Average Game Time And Halftime Show Explained -

Natasha Bure Makes Stunning Confession About Her Marriage To Bradley Steven Perry

Natasha Bure Makes Stunning Confession About Her Marriage To Bradley Steven Perry -

ChatGPT Caricature Prompts Are Going Viral. Here’s List You Must Try

ChatGPT Caricature Prompts Are Going Viral. Here’s List You Must Try -

James Pearce Jr. Arrested In Florida After Alleged Domestic Dispute, Falcons Respond

James Pearce Jr. Arrested In Florida After Alleged Domestic Dispute, Falcons Respond -

Cavaliers Vs Kings: James Harden Shines Late In Cleveland Debut Win

Cavaliers Vs Kings: James Harden Shines Late In Cleveland Debut Win -

2026 Winter Olympics Snowboarding: Su Yiming Wins Bronze And Completes Medal Set

2026 Winter Olympics Snowboarding: Su Yiming Wins Bronze And Completes Medal Set -

Trump Hosts Honduran President Nasry Asfura At Mar-a-Lago To Discuss Trade, Security

Trump Hosts Honduran President Nasry Asfura At Mar-a-Lago To Discuss Trade, Security -

Cuba-Canada Travel Advisory Raises Concerns As Visitor Numbers Decline

Cuba-Canada Travel Advisory Raises Concerns As Visitor Numbers Decline -

Anthropic Buys 'Super Bowl' Ads To Slam OpenAI’s ChatGPT Ad Strategy

Anthropic Buys 'Super Bowl' Ads To Slam OpenAI’s ChatGPT Ad Strategy -

Prevent Cancer With These Simple Lifestyle Changes

Prevent Cancer With These Simple Lifestyle Changes