No permanent enemies

The DUP’s return to the assembly has been made possible by a deal between the party and the British government

Recent developments in Northern Ireland are the latest blow to the notion that peoples and communities nurture ‘ancient hatreds’, which periodically lead to conflict and war.

Northern Ireland, comprising the six predominantly Protestant counties of Ireland, last week elected a Catholic opposed to the partition of Ireland as its ‘first minister’, marking an end to the belief that Catholics and Protestants in the province were destined to fight each other forever.

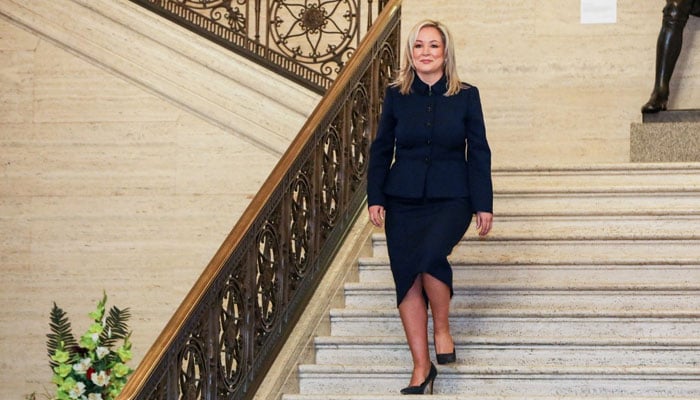

Michelle O’Neill of Sinn Fein (the political wing of the Irish Republican Army) will share power with a die-hard member of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) – the most hardline offshoot of the Unionists, whose belief that Protestants from Ireland’s north formed a distinct nation led to the 1921 partition of Ireland. For thirty years before the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, Northern Ireland was overrun by what is known as ‘the troubles’.

At the time, there was terrorism and insurgency by the Irish Republican Army (IRA), violence against Catholics by hardline Unionists, and use of force by British forces that claimed they were only trying to keep the peace. Catholics, who generally support the reunification of Ireland, and the Unionist Protestants seemed like irreconcilable enemies. But after thirty years of strife, the two sides negotiated a complex power-sharing agreement.

That agreement, too, has had a rocky history. The Northern Ireland Assembly has not always functioned smoothly, mostly because hardline Unionist factions have worried about the erosion of their separate identity and a gradual assimilation into a non-sectarian Ireland. One of the more beneficial results of the truce resulting from the Good Friday Agreement was an improvement in Northern Ireland’s economy. But that has of late been threatened by Britain’s exit from the European Union.

Now, the Irish Republic is still in the European Union while Northern Ireland, as part of the United Kingdom, is not. While both countries were in the EU, Europe could trade freely with both parts of Ireland. Now, the terms of trade with EU member Ireland and non-EU Northern Ireland have changed. The DUP and Sinn Fein were far apart on this and other issues and since the Northern Irish elections of 2022, the DUP had boycotted the Regional Assembly.

The DUP’s return to the assembly has been made possible by a deal between the party and the British government. But, since the real subject of this article is reconciliation between erstwhile enemies and not the minutiae of Northern Ireland’s politics, let us skip to how, once the assembly met, it accepted the result of the 2022 election and allowed a Catholic from Sinn Fein head the government of a Northern Ireland created to have permanent Protestant dominance.

O’Neill is a committed Irish nationalist and belongs to a family that suffered discrimination against Catholics and lost lives in the past decades of conflict. Her deputy first minister, Emma Little-Pengelly, similarly recalls IRA bombings and maintains her Unionist beliefs. But both seem willing to focus on what they can agree upon, instead of insisting on what they must fight about.

O’Neill declared after her election that she would be “a first minister for all” – unionists and republicans, Protestants and Catholics, those who want a ‘united Ireland’ and those who want to remain ‘British forever.’ “None of us are being asked or expected to surrender who we are. Our allegiances are equally legitimate. Let’s walk this two-way street and meet one another halfway,” she added.

Little-Pengelly declared, “Michelle is an Irish republican, and I am a unionist. We will never agree on those issues, but what we can agree on is that cancer doesn’t discriminate, and our hospitals need [to be] fixed.” She explained that a mother in Northern Ireland waiting on her cancer diagnosis was not defined as being republican or unionist. “She is defined by sleepless nights and [the] worry that she may never see her children grow up. The daddy fighting to get the right educational support for his child is not defined by orange or green, but by the stress and anxiety for the future of the child they love.”

The new power-sharing government in Northern Ireland says it will focus on health service reform, school reform, improving public services, and making the region prosperous. In the spirit of reconciliation, O’Neill said, “I am sorry for all the lives lost during the conflict. Without exception,” and added, “I will never ask anyone to ‘move on,’ but I do hope that we can ‘move forward.’”

If Northern Ireland, divided by the sectarianism of its ‘Two Nations Theory’, can move forward with reconciliation, can other nations similarly alienated also find common ground? One can only hope. The key is to set aside the issues that divide and move forward on issues of common concern. One thing is certain, the cliché about ‘ancient hatreds,’ which became popular soon after the breakup of former Yugoslavia is continuously being proved wrong in several parts of the world.

It was incorrect to argue that the Serbs hated the Croats because of what one did to the other during World War II or that the Serbs hated Muslims for taking over Kosovo in 1389. People remember historical wrongs only when they are reminded of them constantly. Hatred is learned behaviour and is often the result of leaders and elites encouraging it. Ending hatred once it has been unleashed is difficult. But in the interim, focusing on shared problems (as is being done in Northern Ireland) is a good idea.

In a speech delivered to the Pakistani National Assembly in December 1996, China’s President Jiang Zemin had advised South Asian nations to pursue a similar approach. He said that as neighbours, “it is difficult not to have some differences or disputes from time to time” but proposed looking at the differences or disputes from “a long perspective.” According to President Jiang, “If certain issues cannot be resolved for the time being, they may be shelved temporarily so that they will not affect the normal state-to-state relations.” In other words, there is no need to have permanent conflict or consider others permanent enemies.

The writer, former ambassador of Pakistan to the US, is Diplomat-in-Residence at the Anwar Gargash Diplomatic Academy in Abu Dhabi and Senior Fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington DC.

-

50 Cent Super Bowl Ad Goes Viral

50 Cent Super Bowl Ad Goes Viral -

'The Housemaid' Lifts Company's Profits: Here's How

'The Housemaid' Lifts Company's Profits: Here's How -

Michael Douglas Recalls Director's Harsh Words Over 'Wall Street' Performance

Michael Douglas Recalls Director's Harsh Words Over 'Wall Street' Performance -

Henry Czerny On Steve Martin Created Humor On 'Pink Panther' Set

Henry Czerny On Steve Martin Created Humor On 'Pink Panther' Set -

Lady Victoria Hervey: Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor's Ex-girlfriend Proud Of Being On Epstein Files

Lady Victoria Hervey: Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor's Ex-girlfriend Proud Of Being On Epstein Files -

Dolly Parton Created One Of Her Iconic Tracks With Acrylic Nails?

Dolly Parton Created One Of Her Iconic Tracks With Acrylic Nails? -

Parents Alarmed As Teens Form Emotional Bonds With AI Companion Chatbots

Parents Alarmed As Teens Form Emotional Bonds With AI Companion Chatbots -

Denzel Washington Surprises LeBron James

Denzel Washington Surprises LeBron James -

Cillian Murphy's Hit Romantic Drama Exits Prime Video: Here's Why

Cillian Murphy's Hit Romantic Drama Exits Prime Video: Here's Why -

Paris Hilton Reveals What Keeps Her Going In Crazy Schedule

Paris Hilton Reveals What Keeps Her Going In Crazy Schedule -

Deep Freeze Returning To Northeastern United States This Weekend: 'Dangerous Conditions'

Deep Freeze Returning To Northeastern United States This Weekend: 'Dangerous Conditions' -

Inside Dylan Efron's First 'awful' Date With Girlfriend Courtney King

Inside Dylan Efron's First 'awful' Date With Girlfriend Courtney King -

'Sugar' Season 2: Colin Farrell Explains What Lies Ahead After THAT Plot Twist

'Sugar' Season 2: Colin Farrell Explains What Lies Ahead After THAT Plot Twist -

‘Revolting’ Sarah Ferguson Crosses One Line That’s Sealed Her Fate As Well As Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s

‘Revolting’ Sarah Ferguson Crosses One Line That’s Sealed Her Fate As Well As Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s -

AI Rivalry Heats Up As Anthropic Targets OpenAI In Super Bowl Ad

AI Rivalry Heats Up As Anthropic Targets OpenAI In Super Bowl Ad -

Kate Middleton, Prince William Share Message Ahead Of Major Clash

Kate Middleton, Prince William Share Message Ahead Of Major Clash