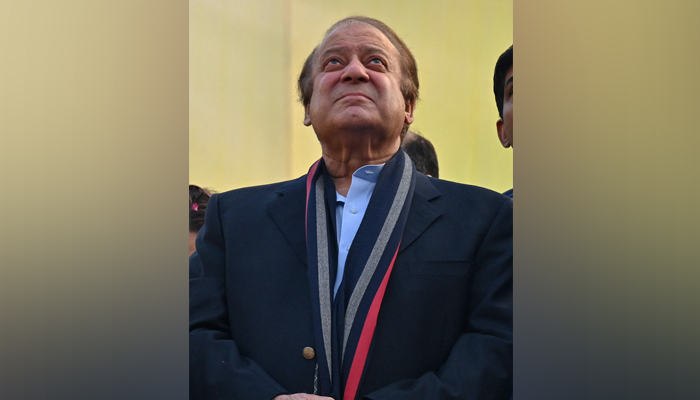

Nawaz — a tapestry of political identities

Exile and tragedies he endured over last many years must have allowed him to reflect on his many years in politics and piece together bigger picture of his political legacy

ISLAMABAD: This is Mian Mohammad Nawaz Sharif’s fourth bid for prime minister — the highest office in the country. The 75-year-old thrice-elected prime minister has several achievements that can vouch for his credibility, and he has also endured myriad challenges that will surely provide him with a roadmap on what to do and, crucially, what not to do this time around.

The exile and tragedies he endured over the last many years must have allowed him to reflect on his many years in politics and piece together the bigger picture of his political legacy.

By any stretch of the imagination, Sharif has suffered most unfair and foul means aimed at sidelining him from power, a trend persisting since 2017 until the recent turn of events following the setback of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) founder Imran Khan’s project.

Leaving aside the tumultuous politics of the 1990s, Sharif and his then arch-rival, twice prime minister Benazir Bhutto, seemed like pawns manipulated by the powerful establishment.

In 2006, Sharif and Benazir signed the Charter of Democracy, aiming for the democratic transition of Pakistan. Pledging to free Pakistan from the influence of unconstitutional and undemocratic forces, they embarked on a joint struggle through parliamentary politics.

Tragically, Benazir was assassinated in a gun and bomb attack in December 2007. Despite this loss, Sharif continued his efforts for political reconciliation and the fortification of democracy. In 2008, he spearheaded a political movement against the repressive regime of military ruler General Pervaiz Musharraf, leading to his ousting from power.

So far so good. Back to the paradoxical man.

Does Sharif know that he represents several contradictions that he is yet to resolve — that he is at once both formidable and weak, charismatic and yet controversial, eagerly brought to office but also unceremoniously kicked out every time? Is Sharif clear on whether he is a democrat or an autocrat who cannot co-exist with others? Is he a strongman or a peacemaker? Having clear answers to these questions will surely be useful in guiding him to another term in office.

On foreign policy, Sharif has always been a strong advocate of the normalisation of relations with India. At a meeting in 2022 in London with this writer Sharif explained why the country was engulfed in poverty and deprivation and blamed it on a selfishly coined narrative that ‘India is an eternal enemy of Pakistan’, which he says has undermined the core economic interest of the country.

To his mind, India cannot take an inch of Pakistan militarily and vice versa.

It should be clear that Sharif seeks good relations with India, but not at the cost of Pakistan’s security. This is amply reflected in Sharif’s tenure in power between 1997 and 1999: on the one hand, Pakistan went nuclear under his command in May 1998 in response to India’s atomic blasts, and on the other, India’s prime minister visited Pakistan on Sharif’s invitation -- one that was extended against the wishes of the military establishment of the time. The former made Sharif a strongman and the latter led to his ouster from office and eventual exile.

His relations with various royal families remain strong and he is well-respected among world leaders he engaged with. This respect, Sharif believes, is premised on his stances on the regional outlook for his country.

Sharif sincerely feels that Pakistan can have cordial relations with India and even the Kashmir issue can be resolved through a negotiated solution. Unfortunately for Sharif, however, sincerity of belief cannot make up for lack of support and the ability to wade through the challenge tactfully: Sharif is not well-read on matters of international politics, and this acts as a severe limitation on his vision.

Regarding Afghanistan, Sharif believes in a pragmatic policy of working with anyone representing the people of the country. He steers clear of virtue signalling on this front, and instead, relies on the demands of statecraft to guide his positions.

Crucially, Sharif is a strong believer in looking eastwards. He wants Pakistan to act as a port of first call for Central Asian states and sincerely believes the country can become a major connectivity hub.

His greatest contribution to Pakistan’s foreign policy was his deepening of relations between China and Pakistan. His actual achievements on this front rank far ahead of any other leader. Unfortunately, he could not garner cross-institutional ownership for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

On the economy, Sharif is at best a mixed bag. He always believed in the private sector as the instrument of change. He started by pushing privatisation and deregulation of a state-controlled economy. Banking, telecom, and industry were sectors where he managed to deliver since the introduction of ambitious reforms his government undertook during his first tenure as PM back in 1990-92.

Had Pakistan adopted and followed those reforms in letter and spirit and manipulated them for political reasons, the country might have been ahead on the economic front in the region.

The then-Indian finance minister and later prime minister Manmohan Singh famously acknowledged Nawaz Sharif’s economic reforms and India followed it.

However, on taxation, Sharif’s performance was less than impressive. He failed to tax and whenever he did, it was not equitable. His exceptional focus on building infrastructure gave Pakistan many concrete icons but he never thought about sustainability.

Effective planning was sacrificed at the altar of rapid implementation and an ambitious development agenda particularly for Punjab, raised questions of equity. Continued protection of retail, real estate and agricultural sectors from taxation meant that a fiscal deficit remained a challenge. When the export sector failed to perform, rising imports resulted in twin deficits (trade and budget).

Unfortunately, Sharif never moved out of Darnomics, which resulted in reverse budgeting and elite capture of state institutions. Repeated tax immunities added to the transparency problem and encouraged the perception of reckless economic management.

At the macro level, he is a complete capitalist and believes in the trickle-down effect which however never materialised. So, the state continued to finance its deficits on both ends by more borrowing, something that haunts Pakistan today. Despite all this, Sharif’s performance on the economic front remains better than any of his competitors.

What about his democratic credentials? Amazingly, someone thrown out thrice as an elected leader is again the country’s best bet.

Is it correct that Sharif has given up on his narrative of civilian supremacy to the politics of pragmatism? If so, what has brought him to this point? The answer to these questions is quite simple: Sharif is a man of contradictions, an odd blend of weaknesses and strengths.

He can withstand great pressures but also has his fair share of meltdowns at mere whispers. He can take a stand on something politically inconsequential but then can decide to give in to the advice of someone he considers his well-wisher.

He can put everything at stake, including his own life, without any apparent justification or reason. His decisions are based often not on principles or ideology, but rather on the moment he is living in.

The following can demonstrate this. General Raheel asked Sharif for an extension and did everything to convince him but to no avail. Sharif was promised closure of the Panama cases and an uninterrupted completion of his tenure as PM and beyond, but Sharif didn’t budge. People warned him about political instability and consequences on the delicately poised economy, yet he refused.

Then why did he agree to vote for the law for General Bajwa’s extension in 2019? Did the principles change or the fortunes? Was it political brinkmanship or political expediency? The argument that he did it because his senior party colleagues forced him to does not stand.

So, the question of whether such decisions are driven by personal ambition or wider political interests remains unanswered.

Finally, has Sharif, after 40 years in politics, formed a real political party? A party with an agenda for socio-economic change? A party with a vision for a more equitable state and society? A party with a grassroots organisational structure that can stand against undemocratic forces and enforce the will of the people? A party that believes in an ideology or a set of principles, which remain at play, whether in or out of the government? The simple and honest answer to all the above is a resounding ‘NO’.

The writer is the director of news at Geo News. He tweets/posts @ranajawad

-

'The Muppet Show' Star Miss Piggy Gives Fans THIS Advice

'The Muppet Show' Star Miss Piggy Gives Fans THIS Advice -

Sarah Ferguson Concerned For Princess Eugenie, Beatrice Amid Epstein Scandal

Sarah Ferguson Concerned For Princess Eugenie, Beatrice Amid Epstein Scandal -

Uber Enters Seven New European Markets In Major Food-delivery Expansion

Uber Enters Seven New European Markets In Major Food-delivery Expansion -

Hollywood Fights Back Against Super-realistic AI Video Tool

Hollywood Fights Back Against Super-realistic AI Video Tool -

Meghan Markle's Father Shares Fresh Health Update

Meghan Markle's Father Shares Fresh Health Update -

Pentagon Threatens To Cut Ties With Anthropic Over AI Safeguards Dispute

Pentagon Threatens To Cut Ties With Anthropic Over AI Safeguards Dispute -

Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026: What To Expect On February 25

Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026: What To Expect On February 25 -

Travis Kelce Takes Hilarious Jab At Taylor Swift In Valentine’s Day Post

Travis Kelce Takes Hilarious Jab At Taylor Swift In Valentine’s Day Post -

NASA Confirms Arrival Of SpaceX Crew-12 Astronauts At The International Space Station

NASA Confirms Arrival Of SpaceX Crew-12 Astronauts At The International Space Station -

Can AI Bully Humans? Bot Publicly Criticises Engineer After Code Rejection

Can AI Bully Humans? Bot Publicly Criticises Engineer After Code Rejection -

Search For Savannah Guthrie’s Abducted Mom Enters Unthinkable Phase

Search For Savannah Guthrie’s Abducted Mom Enters Unthinkable Phase -

Imagine Dragons Star, Dan Reynolds Recalls 'frustrating' Diagnosis

Imagine Dragons Star, Dan Reynolds Recalls 'frustrating' Diagnosis -

Steve Jobs Once Called Google Over Single Shade Of Yellow: Here’s Why

Steve Jobs Once Called Google Over Single Shade Of Yellow: Here’s Why -

Barack Obama Addresses UFO Mystery: Aliens Are ‘real’ But Debunks Area 51 Conspiracy Theories

Barack Obama Addresses UFO Mystery: Aliens Are ‘real’ But Debunks Area 51 Conspiracy Theories -

Selma Blair Explains Why Multiple Sclerosis 'isn't So Scary'

Selma Blair Explains Why Multiple Sclerosis 'isn't So Scary' -

Will Smith Surprises Wife Jada Pinkett With Unusual Gift On Valentine's Day

Will Smith Surprises Wife Jada Pinkett With Unusual Gift On Valentine's Day