The lost gems of Sindh ( Part – I)

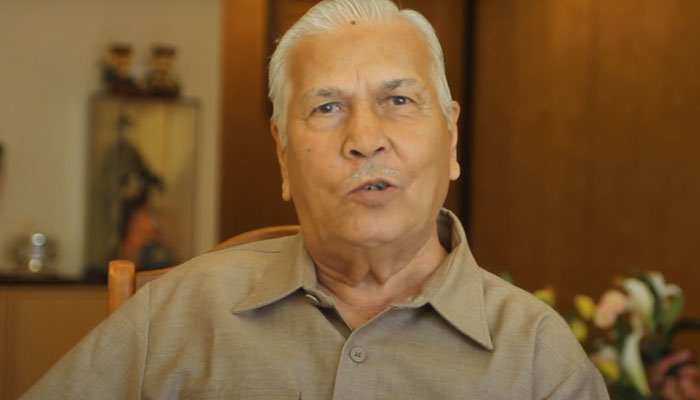

The second half of the year 2023 has deprived Sindhi literature of two giants: Murlidhar Jetley and Wali Ram Vallabh. Both of whom remained immersed in their world of research, translations and writings for over 60 years.

Murlidhar died in July this year at the age of 93 in Delhi; Wali Ram aged 82 passed away in November in Karachi.

My first introduction with Murlidhar was through comrade Jam Saqi in 1984. That was the time when Pakistan was under the yoke of the third military dictator Gen Ziaul Haq.

The Movement for Restoration of Democracy was in full swing; most opposition leaders were either in jail or in exile. In Sindh, nearly all the leftist, nationalist, and progressive leaders such as Fazil Rahu, GM Syed, Jam Saqi, Prof Jamal Naqvi, and Rasool Bux Palijo and student leaders such as Imdad Chandio were in prison.

Jam Saqi was not well and martial-law authorities had to shift him to Jinnah Hospital in Karachi. My friend Jawaid Bhutto – who was later killed in the US – and I were leaving for our first international travel to India. When we met Jam Saqi for a farewell meeting in hospital, he gave us two books by Dr Tanveer Abbasi – a renowned Sindhi poet and researcher – for Dr Murlidhar in Delhi. We met him and handed over the books; he was overjoyed at these presents and remembered his hometown Hyderabad with misty eyes.

He talked about the areas of Hyderabad where he spent his childhood: Shahi Bazaar and Herabad that, according to Jetley, Sindhi Amils had established. He vividly remembered lanes and by-lanes that he used to frequent as a child, and asked Jawaid Bhutto if Advani lane, Malkani lane, Tilak Charhi, and Phuleli still carried the same names.

He went into a trance while talking about his grandfather’s clinic and the three houses their family owned in Hyderabad but had to leave to save their lives. He told us that there were nearly two dozen Jetley families residing mostly in southern cities such as Hyderabad, Karachi, and Mirpur Khas.

While Murlidhar Jetley was born in 1930 in Hyderabad, Wali Ram Vallabh opened his eyes in 1941 in Mithi, Tharparkar. At the time of Partition, the situation in Mithi was not as intense and hateful as it became in other cities like Hyderabad, Karachi, and Sukkur. Riots mostly took place in cities from where rich Hindus had to flee as their properties came under attack.

The Jetley family was one of them. Just as Muslims were at the receiving end of violence in India, the same happened to most Hindus in the new state of Pakistan.

Both Murlidhar and Wali Ram had in common their love for language and literature. Both were proficient in at least five languages: English, Hindi, Sanskrit, Sindhi, and Urdu. Following the creation of Pakistan, not all Hindus migrated. Despite all odds, Wali Ram Vallabh’s family stayed in Pakistan while Jetley’s family migrated to Indias.

Since there were many Jetley families living in Bombay (now Mumbai), Gujarat, and Rajasthan, they tried their best to help refugees from Pakistan.

Jetley narrated to us how he and his family had to leave Pakistan under tremendous pressure and how he longed to be back to his birthplace. The main reason for their migration was the question of safety and survival that was under threat. These Sindhis in India initially found themselves landless and stateless but gradually spread across many states in the country and even settled in Africa, Europe, the Middle East, South East Asia, and the US.

Murlidhar Jetley recalled how in Bombay and Delhi there were small communities of Sindhis who found it challenging to mingle with the local population – much in the same fashion as Muslim migrants from India initially faced in Pakistan.

The Jetley family locked the doors of their home in Hyderabad in August 1947 and moved to Rajasthan waiting for the situation to normalize so that they could come back, but that never happened. Murlidhar Jetley narrated to us how he performed a daring feat in December 1947 to come back alone from Abu Road city in Rajasthan to Hyderabad just to rescue his boxes of books. He managed to transport nearly a dozen boxes that he was proud to have kept in safe and sound condition for decades.

Intellectuals such as Jetley took it upon themselves to keep the torch of Sindhi culture and language alive in India. By the mid-1980s, it had nearly been four decades since those tumultuous days of Partition, but there was still a strong Sindhi presence in India that resonated in their traditions.

However he had serious concerns about the survival of the Sindhi language among the new generations of Sindhis who were less interested in their language and traditions. Awareness of their cultural identity was on the decline and Murlidhar Jetley was trying to revive the only force that could connect and bind dispersed Sindhis across the globe.

As Sindhi started losing ground to other local languages in India, the battle that Jetley was fighting had an active front. He knew that Sindhi was in danger of being extinct and that forceful preventive measures were of significance to win that battle. Jetley shared with us that the number of Sindhi-teaching schools were over a thousand in the 1950s, but the number gradually declined, and in the 1980s there were hardly 100 such schools.

Wali Ram Vallabh on the contrary did not have to face the question of the survival of Sindhi language though when he was in his 20s there were some attempts by the One-Unit government to close down Sindhi schools.

In India, Murlidhar Jetley started teaching Hindi and Sanskrit at a school and resumed his education, ultimately obtaining a PhD from Pune University in 1965. He was the first scholar in India to do his research in morphology of the Sindhi language and acquire a PhD in Sindhi.

His friend Lachman Khubchandani joined him after doing his PhD from the US, and they joined hands to work on the project of compiling the Sindhi-English dictionary which took decades. In the meantime, Murlidhar Jetley also worked as a Hindi teacher and a sub-editor at a weekly newspaper.

He formed a close bond with Sindhi literature in India. In 1966, Delhi University appointed him as a lecturer of Sindhi and later as reader. When we met him in the mid-1980s, he had been teaching Sindhi and comparative Indian literature for nearly two decades.

Murlidhar Jetley retired at the age of 65 and then devoted most of his time to writing in English, Hindi, and Sindhi. His topics mostly revolved around Sindhi language and literature. He did multiple research projects on the evolution and history of Sindhi. When we met him, he presented two of his books to us: ‘Sindhi Sahitya jo Itahas’ (History of Sindhi Literature) and ‘Shah Je Risale Jo Abhyas’ (Study of Shah jo Risalo).

By the time of his death, Dr Murlidhar Jetley had contributed at least 25 books in English, Hindi, and of course in Sindhi – his first language. He also had to his credit more than 100 research articles and papers.

To be continued

The writer holds a PhD from the University of Birmingham, UK. He tweets/posts @NaazirMahmood and can be reached at: mnazir1964@yahoo.co.uk

-

Kanye West's Last Measure To Save Bianca Censori Marriage As He Tries To Salvage Image

Kanye West's Last Measure To Save Bianca Censori Marriage As He Tries To Salvage Image -

Kim Kardashian Finally Takes 'clear Stand' On Meghan Markle, Prince Harry

Kim Kardashian Finally Takes 'clear Stand' On Meghan Markle, Prince Harry -

Christina Applegate Makes Rare Confession About What Inspires Her To Keep Going In Life

Christina Applegate Makes Rare Confession About What Inspires Her To Keep Going In Life -

Patrick J. Adams Shares The Moment That Changed His Life

Patrick J. Adams Shares The Moment That Changed His Life -

Selena Gomez Getting Divorce From Benny Blanco Over His Unhygienic Antics?

Selena Gomez Getting Divorce From Benny Blanco Over His Unhygienic Antics? -

Meet Arvid Lindblad: Here’s Everything To Know About Youngest F1 Driver And New Face Of British Racing

Meet Arvid Lindblad: Here’s Everything To Know About Youngest F1 Driver And New Face Of British Racing -

At Least 30 Dead After Heavy Rains Hit Southeastern Brazil, 39 Missing

At Least 30 Dead After Heavy Rains Hit Southeastern Brazil, 39 Missing -

Courtney Love Recalls How ‘comparison’ Left Marianne Faithfull ‘broken’

Courtney Love Recalls How ‘comparison’ Left Marianne Faithfull ‘broken’ -

Pedro Pascal Confirms Dating Rumors With Luke Evans' Former Boyfriend Rafael Olarra?

Pedro Pascal Confirms Dating Rumors With Luke Evans' Former Boyfriend Rafael Olarra? -

Ghost's Tobias Forge Makes Big Announcement After Concluding 'Skeletour World' Tour

Ghost's Tobias Forge Makes Big Announcement After Concluding 'Skeletour World' Tour -

Katherine Short Became Vocal ‘mental Illness’ Advocate Years Before Death

Katherine Short Became Vocal ‘mental Illness’ Advocate Years Before Death -

SK Hynix Unveils $15 Billion Semiconductor Facility Investment Plan In South Korea

SK Hynix Unveils $15 Billion Semiconductor Facility Investment Plan In South Korea -

Buckingham Palace Shares Major Update After Meghan Markle, Harry Arrived In Jordan

Buckingham Palace Shares Major Update After Meghan Markle, Harry Arrived In Jordan -

Demi Lovato Claims Fans Make Mental Health Struggle Easier

Demi Lovato Claims Fans Make Mental Health Struggle Easier -

King Hospitalized In Spain, Royal Family Confirms

King Hospitalized In Spain, Royal Family Confirms -

Japan Launches AI Robot Monk To Offer Spiritual Guidance

Japan Launches AI Robot Monk To Offer Spiritual Guidance