The stark realities of Shigar Valley

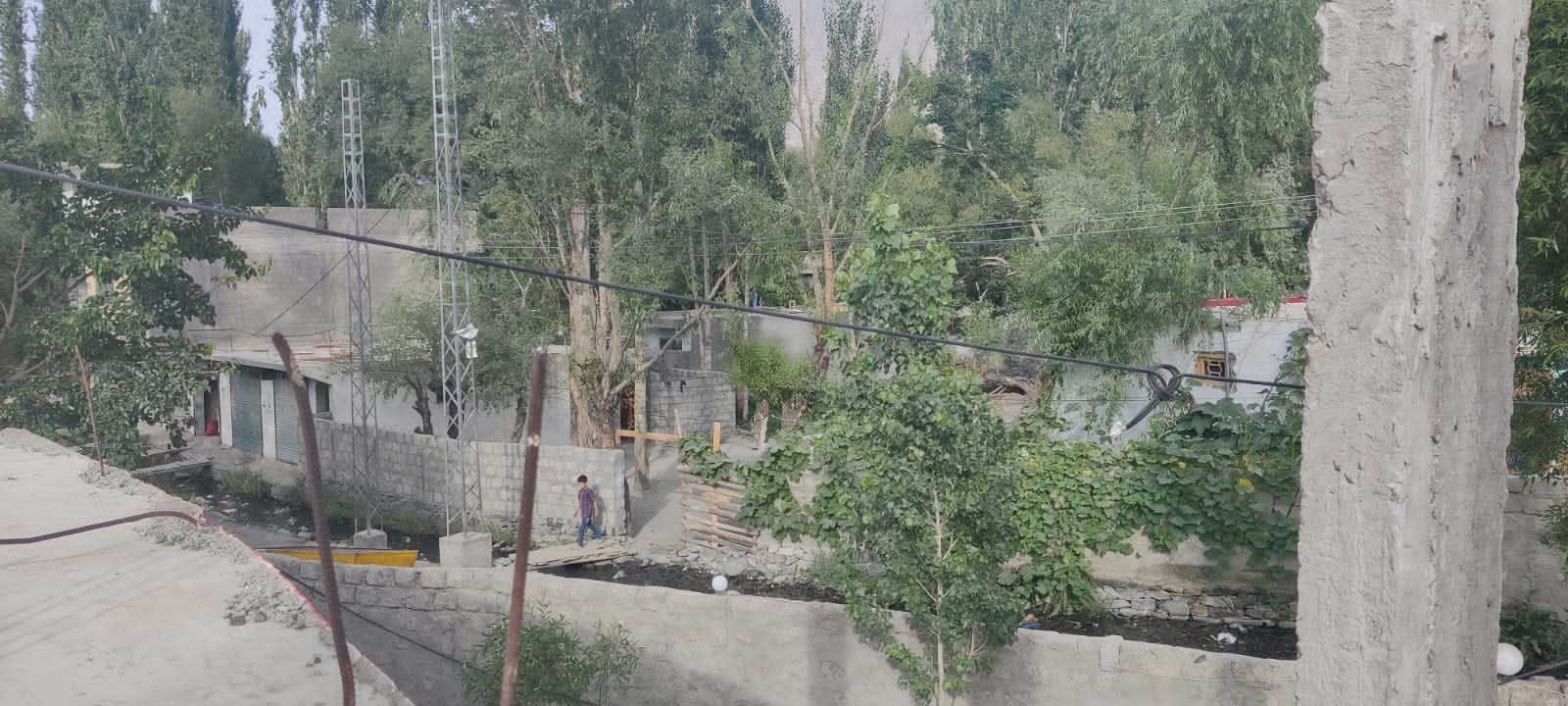

The living conditions in Shigar Valley showcase abject poverty

Shigar Valley sits in the Karakoram Mountain range, home to some of the tallest mountains in the world, including K2.

Shigar Valley is a district and geographic silo within Gilgit-Baltistan, a province in the north of Pakistan. This region was only given provincial status in 2020, and as such its administrative legitimacy, autonomy, and effectiveness is limited at best.

The living conditions in Shigar Valley showcase abject poverty. When someone exposed to the Western press tries to imagine what life in the underdeveloped world is like, Shigar Valley tragically matches this picture in many respects. Despite being a very peaceful region safe from overt violence, its underdevelopment presents equally direct, structural violence in the domains of economy, health, education, and basic material needs.

The lack of effective economic investment in Shigar has rendered its economy highly dependent on a rapacious, seasonal tourism industry. Every summer, the region becomes hospitable to mountaineers eager to explore and scale mountains in the Karakoram range, which hosts 18 peaks above 7,500m and four peaks above 8,000m, including the infamous K2.

A handful of companies (read: wealthy families) operate this business by employing male labourers as porters, cooks, and guides. For Balti people, this is the best paying work available at this time of year and yields a whopping 80$ over a 15-day trek as the starting pay for a porter. During our trek there, the desperation of these workers was immediately apparent given the life-threatening nature of the work. It is all too common for porters to suffer crippling injury or lose their lives to this work due to insufficient experience, equipment, or health, as well as a general lack of regard for the lives of these people. Read the story of porter Mohammad Hassan.

Despite the already meagre wages and life-threatening working conditions, the wealthy families operating these companies often refuse to pay full wages to workers at the end of the treks on the false basis that these workers did not complete their full duties. When I went on our trek, this happened to our crew. We knew our crew and the quality of work they performed, as well as the many challenges they had to overcome. When we demanded that the man in charge of operations pay the full wages, the owners failed to take responsibility – many of the workers have still not received their payment.

One such worker was the cook for our crew, Syed Hassan, a very hardworking and dedicated man who demonstrated strong leadership when he helped guide our trek home through many unexpected hurdles. Syed Hassan contracted tuberculosis two months ago and has received inadequate medical care. He has lost much of his mental clarity and is unable to perform physical labour. Although my uncle is currently supporting him financially, maintaining contact remains a challenge due to poor connectivity in the region and his deteriorating health.

Food is preventive medicine. When you lack access to adequate nutrition and clean water, the body develops chronic conditions, and the immune system is rendered weak and unable to fight infections.

The food ration allotted for porters is flour, salt, sugar, baking soda, and tea. This is what they survive on whilst carrying up to 25kg on their backs for 15-20 km every day without hiking boots or adequate clothing for the cold. Lacking access to water filtration methods, they must drink water from the glacial rivers, streams, waterfalls in which one can visibly see sediment floating. I remember seeing two porters drinking water that they gathered from the river. The water was visibly brown.

It came as no surprise that so many men we talked to had developed UTIs and other kidney diseases. It is also no surprise that Syed Hassan contracted tuberculosis. How can you have a strong immune system when you have such inadequate nutrition? How can you provide for your family reliably when company owners refuse to honour their end of the contract?

While the men engage in the mountaineering business, women stay in the villages and tend to families and fields. Agriculture is widespread but insufficient to have food sovereignty. In such harsh conditions, Balti people in Shigar Valley lack the technology, training, and infrastructure to grow sufficient and sufficiently diverse food to provide adequate, healthy nutrition. While my level of contact with the plight and lives of women in Baltistan was limited at best, it was obvious that there were no older women around. Why is the life expectancy so short for women and men in Baltistan?

When the tourism season is over as winter turns, men depart Baltistan in search of labour in other parts of Pakistan. Some go to Gilgit, others to big cities like Lahore, Islamabad, or Karachi, depending on where they have contacts. The labourers save little money during this time but become one less mouth to feed back at home; they return at the turn of spring in more or less the same position as last year.

Actually, it would be a marginal success if they returned to the same position as the previous year. Lack of a price stabilization programme in Pakistan has led to horrific spikes of inflation over the last many years, sending costs of living through the roof with no end in sight.

The level of education in Baltistan is a large culprit in their plight. While most people complete their matric exam, given at the 10th year of their studies, few manage to study beyond this. The reason being that they only got to the matric exam because their teachers passed students along despite learning little to none, and as a result these students have no hope of engaging with the demands of higher-level education. While literacy is widespread, intellectual skills are severely underdeveloped and limited by poverty. There is also a lack of vocational education programmes. How can a region advance if its population lacks pragmatic education?

Shigar Valley presents an uneducated, malnourished, unskilled labour force in an extremely harsh climate. None of this is inevitable or necessary. There is a need for adequate, effective investment and the placement and cultivation of human resources with careful, critical planning. A successful approach requires both short- and long-term vision. There needs to be a focus on survival needs – food, water, healthcare – and then on social development like education and job creation. A population cannot advance if it cannot survive.

Without survival programmes, the Balti people will continue to lose their livelihoods and loved ones.. However, we cannot be short-sighted. We must consider how to simultaneously develop schools that provide practical, effective education tailored towards understanding and transforming material conditions in Baltistan while also creating jobs through local infrastructure projects.

Employing and training local labourers on projects such as building roads, upgrading homes, installing water systems, building public facilities for hygiene, tourism facilities. Such circular development can strengthen the local economy and create self-sufficiency and regional autonomy. If it takes 100 years then so be it, but let us begin today.

The writer is an educator and activist currently based in Vietnam. He is raising funds and organizing relief for poor families in Baltistan.

-

Kelly Clarkson Ready To Date After Talk Show Exit?

Kelly Clarkson Ready To Date After Talk Show Exit? -

Is AI Heading Into Dangerous Territory? Experts Warn Of Alarming New Trends

Is AI Heading Into Dangerous Territory? Experts Warn Of Alarming New Trends -

Google Updates Search Tools To Simplify Removal Of Non-consensual Explicit Images

Google Updates Search Tools To Simplify Removal Of Non-consensual Explicit Images -

Chilling Details Emerge On Jeffrey Epstein’s Parties: Satanic Rights Were Held & People Died In Rough Intimacy

Chilling Details Emerge On Jeffrey Epstein’s Parties: Satanic Rights Were Held & People Died In Rough Intimacy -

50 Cent Gets Standing Ovation From Eminem In New 'award Video'

50 Cent Gets Standing Ovation From Eminem In New 'award Video' -

Bad Bunny Delivers Sharp Message To Authorities In Super Bowl Halftime Show

Bad Bunny Delivers Sharp Message To Authorities In Super Bowl Halftime Show -

Prince William 'worst Nightmare' Becomes Reality

Prince William 'worst Nightmare' Becomes Reality -

Thai School Shooting: Gunman Opened Fire At School In Southern Thailand Holding Teachers, Students Hostage

Thai School Shooting: Gunman Opened Fire At School In Southern Thailand Holding Teachers, Students Hostage -

Britain's Chief Prosecutor Breaks Silence After King Charles Vows To Answer All Andrew Questions

Britain's Chief Prosecutor Breaks Silence After King Charles Vows To Answer All Andrew Questions -

Maxwell Could Get 'shot In The Back Of The Head' If Released: US Congressman

Maxwell Could Get 'shot In The Back Of The Head' If Released: US Congressman -

New EU Strategy Aims To Curb Threat Of Malicious Drones

New EU Strategy Aims To Curb Threat Of Malicious Drones -

Halle Berry On How 3 Previous Marriages Shaped Van Hunt Romance

Halle Berry On How 3 Previous Marriages Shaped Van Hunt Romance -

Facebook Rolls Out AI Animated Profile Pictures And New Creative Tools

Facebook Rolls Out AI Animated Profile Pictures And New Creative Tools -

NHS Warning To Staff On ‘discouraging First Cousin Marriage’: Is It Medically Justified?

NHS Warning To Staff On ‘discouraging First Cousin Marriage’: Is It Medically Justified? -

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor Flew Money In Suitcases To Launder: New Allegation Drops

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor Flew Money In Suitcases To Launder: New Allegation Drops -

Nancy Guthrie Abduction: Piers Morgan Reacts To 'massive Breakthrough' In Baffling Case

Nancy Guthrie Abduction: Piers Morgan Reacts To 'massive Breakthrough' In Baffling Case