Benefits of GSP-Plus status yet to trickle down to Pakistan’s largely undocumented workforce

Karachi

More than 72 percent of Pakistan’s labour force is involved in informal economy in which people continue to toil without any documentation or agreement with their employers and have yet to see the benefits of international trade agreements signed by Pakistan.

The country has a labour force of 61.04 million engaged in diverse sectors of economy and at various levels of occupations, out of which the bulk of non-agriculture labour force, 72.6 per cent, is informally employed.

Even if the agricultural work force is included, an overwhelming percentage of the total labour force still toils under informal work arrangements lacking any documentation.

This was stated in a report released by the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER) on Wednesday titled “Status of Labour rights in Pakistan”.

The study documents the well-known notion that the current status of majority of the work force in Pakistan is characterized by low wages, long working hours, poor health and safety conditions, rising contractual work, besides increasing restrictions on freedom of association and collective bargaining.

It questions the efficacy of various trade agreements Pakistan has entered into by stating: “Enhanced exports of textile under the GSP-Plus scheme have not filtered down to workers while compliance of international standards on working conditions linked to the GSP-Plus remains weak.”

Speaking at the launch ceremony held at the Karachi Press Club, Geoff Brown, a trade union trainer from United Kingdom, appreciated the efforts of PILER and said it was as important for the international community to know about workers’ conditions in Pakistan and their relationship with policymakers and the civil society.

Brown praised the last chapter of the report, “Union Power Sharing”, authored by Zeenia Shaukat, saying that it was important because of its interesting description of how labour unions in Pakistan operated on complete self-reliance, while showing strong solidarity with fellow labour organisations.

“This shows that the labour force still has the potential to bring changes,” said Brown. “They can raise important political and legal questions that can lead to make Pakistan a better place for workers.”

Habibuddin Junaidi, a senior trade union leader, said Pakistan was one of the few countries that passed a lot of labour-related laws but implemented them the least.

Giving an example, he said the government had notified Rs13,000 per month to be the minimum wage but it was hardly followed through in letter and spirit because in most industrial units, labour was outsourced through a third party that hired workers under a contractual system. In 1997, he said, there had been 80,000 labourers affiliated with trade unions in the country but now the number had dropped down to 12,000.

Highlighting the impact of contractual employment in banks, Junaidi said that only 15 percent of the employees were regular workers. In some organisations including banks, he said, contractual workers were not even allowed to even visit the canteen.

Karamat Ali, the executive director of PILER said that lack of documentation about labour issues was a grave concern that added to government apathy and deterioration of working labour conditions.

“The real wage of labour is actually decreasing, leaving workers in dire financial conditions. According to a report by Unicef, one of the basic reasons behind malnutrition in Sindh is because the real wage is very low,” he said. “By paying such low wages for the working class, we then wonder why people become criminals.”

Labour legislation

The report rightly points out that even after five years of the passage of 18th Amendment, the federal government failed to come up with a blueprint to harmonize labour laws across provinces.

It recommends a “broader national legislative labour framework based on constitutional rights and international labour standards, and a statutory/constitutional mechanism to ensure provincial laws adhere to this blueprint remained to be devised till the end of 2015.”

Child labour

“The existing labour laws that allow individuals, fourteen years old and above, to engage in productive activity but it remains to be brought in sync with Article 25-A calling for universal education from ages five to sixteen,” the report highlights.

New labour laws enacted by the provinces have ignored this essential aspect that the definition of a child is still the same: fourteen years.

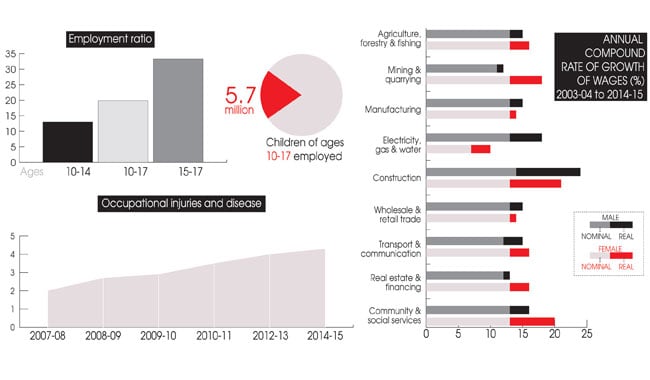

According to a 2015 publication of International Labour Organisation on child labour in South Asia, figures reveal that out of Pakistan’s total work force, 5.7 million are children of ages between 10 and 17 years, comprising 19.9 percent of the total labour volume.

The employment ratio for 10-14 year olds is 13 percent and increases to 33.3 percent for children between 15-17 years.

“More than two-thirds of working children between the ages of 10-17 in Pakistan were employed in the agricultural sector. A similar proportion of employed children, 67.9 per cent, were engaged in unpaid family work, with the remaining 32.1 percent were paid workers or self-employed,” the report finds.

Trade unions

According to latest available non-official data, there are 949 registered trade unions with a total membership of 1,865,141 people, amounting to three percent of the total workforce, the report reveals.

Moreover, it has also been pointed out that Pakistan has not yet ratified the ILO Labour Statistics Convention No.160 (1985) that mandates countries to regularly collect, compile and publish basic labour statistics.

Moreover, labour force participation rate declined from 45.5 percent to 45.2 percent. The decline occurred in workers between 10 and 24 years, and was indicative of increasing youth unemployment due to factors including skill mismatch, low employment generation, but this has yet to be determined through surveys conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

It is to be noted that Pakistan’s labour force participation rate is among the lowest in the world. In advanced economies, labour force participation rates are above 70 percent. The reasons for overall low labour force participation in Pakistan include poor job growth, lack of skills and poor education of potential work force.

Gender disparity

According to the study, a wide disparity between men (67.8 per cent) and women (22 percent), comprising the labour force, refined activity participation rates. Women’s low participation rate, the lowest in South Asia, was due to lower human development indicators for women including literacy, skills, health, besides cultural constraints inhibiting women’s mobility and participation in economic and public affairs.

National wages

“According to the latest figures issued by Pakistan LFS 2014- 2015, the national average monthly wage stood at Rs14,971. However, agricultural workers earned Rs7,804 per month, half of the national average,” it was said.

“With the average family size of 6.8 percent and 1.5 earning members per family in Pakistan, the monthly income of rural family translated into Rs57 (half a dollar) per person, per day, in a rural household.”

Meanwhile, though textile and garment industries comprise the largest and the most important component of the manufacturing sector, workers in the manufacturing sector earned less than the national average of Rs13,478.

The report states that after granting of the GSP-Plus tariff-free scheme, textile contributed 57 percent of the total export in the fiscal year 2014-15.

However, the revenue earned by the manufacturing sector workers indicates that the benefit of enhanced exports is not trickling down to the workers. “The gender difference in wages was mind boggling: women workers are getting Rs5,435 per month compared to male workers who earn Rs14,465.”

Occupational safety

The study lamented that Pakistan slid further down the occupational safety and health score in 2015.

“The largest group of victims of workplace injuries and diseases belonged to the agriculture and fisheries sector where 51.2 percent workers reported work-related health hazards.”

Baldia factory case

The report also summarises the aftermath of Baldia factory fire and the concerns associated with the case. It states: “By the end of 2015, all suspects were on bail. The accused owners of the factory did not attend the court hearing for 14 months but sent applications for exemption on medical grounds. The workers who survived the disaster but were injured received compensation from the court in initial proceedings of the case. Two survivors who became completely disabled after the incidence received the compensation worth Rs600,000 from the court. Forty-five survivors who recovered from minor injuries found employment as contract workers in other factories in the same area.”

It said out of the total 1,500 workers employed in the factory at the time of incidence, it was the skilled workers who found employment. But many unskilled labour including loaders and cleaners, became jobless after the factory was burnt to the ground.

-

YouTube Tests Limiting ‘All’ Notifications For Inactive Channel Subscribers

YouTube Tests Limiting ‘All’ Notifications For Inactive Channel Subscribers -

'Isolated And Humiliated' Andrew Sparks New Fears At Palace

'Isolated And Humiliated' Andrew Sparks New Fears At Palace -

Google Tests Refreshed Live Updates UI Ahead Of Android 17

Google Tests Refreshed Live Updates UI Ahead Of Android 17 -

Ohio Daycare Worker 'stole $150k In Payroll Scam', Nearly Bankrupting Nursery

Ohio Daycare Worker 'stole $150k In Payroll Scam', Nearly Bankrupting Nursery -

Michelle Yeoh Gets Honest About 'struggle' Of Asian Representation In Hollywood

Michelle Yeoh Gets Honest About 'struggle' Of Asian Representation In Hollywood -

Slovak Fugitive Caught At Milano-Cortina Olympics To Watch Hockey

Slovak Fugitive Caught At Milano-Cortina Olympics To Watch Hockey -

King Charles Receives Exciting News About Reunion With Archie, Lilibet

King Charles Receives Exciting News About Reunion With Archie, Lilibet -

Nvidia Expands AI Infrastructure With Nevada Data Centre Lease

Nvidia Expands AI Infrastructure With Nevada Data Centre Lease -

Royal Family Shares Princess Anne's Photos From Winter Olympics 2026

Royal Family Shares Princess Anne's Photos From Winter Olympics 2026 -

Tori Spelling Feels 'completely Exhausted' Due To THIS Reason After Divorce

Tori Spelling Feels 'completely Exhausted' Due To THIS Reason After Divorce -

SpaceX Successfully Launches Crew-12 Long-duration Mission To ISS

SpaceX Successfully Launches Crew-12 Long-duration Mission To ISS -

PlayStation State Of Play February Showcase: Full List Of Announcements

PlayStation State Of Play February Showcase: Full List Of Announcements -

Ed Sheeran, Coldplay Caught Up In Jeffrey Epstein Scandal

Ed Sheeran, Coldplay Caught Up In Jeffrey Epstein Scandal -

US, China Held Anti-narcotics, Intelligence Meeting: State Media Reports

US, China Held Anti-narcotics, Intelligence Meeting: State Media Reports -

Paul Anthony Kelly Reveals How He Nailed Voice Of JFK Jr.

Paul Anthony Kelly Reveals How He Nailed Voice Of JFK Jr. -

Victoria, David Beckham React To Marc Anthony Defending Them Amid Brooklyn Drama

Victoria, David Beckham React To Marc Anthony Defending Them Amid Brooklyn Drama