SC declares domicile parent document for recruitment

ISLAMABAD: The Supreme Court has ruled that a person’s domicile is treated as parent document for recruitment purposes to determine the permanent abode.

A three-member bench of the apex court, headed by Justice Sardar Tariq Masood and comprising Justice Aminuddin Khan and Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar, dismissed the petitions challenging the verdict of the Peshawar High Court.

According to Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar who authored the judgment, a person’s domicile is generally treated as a parent document for recruitment purposes to determine the permanent abode.

“In the wake of the above discussion, we do not find any irregularity or perversity in the impugned judgments passed by the learned high court, and the civil petitions are therefore dismissed and leave is refused,” says the written order of the court.

The court held that all the respondents unequivocally asserted that they possess the domiciles of the UCs concerned as a matter of course and also offered valid justifications for the intermittent change of address, with further affirmation that the place of their permanent residence is as per their domiciles.

The court observed that it is clear from the provisions of Citizenship Act that neither a person can obtain multiple domiciles nor does the law approve or allow any such act or practice.

The court held that if jobs are given solely based on the CNIC without taking into account the address on domicile, it will create various complications and complexities. Even in the case of temporary shifting or a rented house, the person will be forced every time to apply for a new domicile with the address of the changed abode. In such an event, he will be neither here nor there, but unfortunately, a rolling stone, who would never be able to get a job due to the discrepancy.

“So for all intents and purposes, the weightage and preference should be given first to the certificate of domicile, which cannot be ignored without due consideration,” the court noted.

“In our considerate view, no restrictive or dissuasive interpretation of Section 3 of the 2011 Act can be accentuated or overextended to nullify and abolish the effect of the certificate of domicile and/or to give preference to the CNIC over the domicile, and if it is done, then it will render the entire concept of a domicile redundant and meaningless in the recruitment process,” says the judgment.

The court noted that according to the corrigendum issued under the original advertisement published in two Urdu dailies on 22.1.2016 and 24.1.2016, one more condition was added: female candidates may also apply based on the husband’s domicile.

The court noted that the candidate claimed to be placed at Serial No. 8 on the merit list out of seven vacant posts, and Muhammad Amir, who was at Serial No3, opted for some other job. Therefore, the directions given by the learned high court to consider the candidature of Syed Amjad Rauf Shah on the vacant post, who was next in line on merit within the same recruitment process, seems to be a rational conclusion in the present set of circumstances.

“One more crucial aspect cannot be lost sight of: all the respondents were allowed to compete in the aptitude tests for appointment on an ad hoc, contract, or permanent basis as per the advertisement; they qualified for the test; some of them secured top positions, and collectively all of them were declared eligible, but they were dropped from the merit list,” says the judgment.

The court held that if the department had any doubt about the address as mentioned in the domicile and CNIC, then why was due diligence not done at the time of scrutiny of application forms or at the time of shortlisting the candidates, which was an appropriate stage to vet all the credentials and antecedents of each candidate? And, in case of any objection, the candidate could be confronted and asked to remove the objection before joining the recruitment process.

“Thus, the conduct of the department is not above board,” the court held, adding that nothing was said regarding any vetting of documents made before allowing the candidates to appear for the aptitude test, and despite qualifying the test based on documents submitted by them and securing marks on merit, they were denied the job opportunity at the eleventh hour, which is also against the doctrine of legitimate expectation.”

According to the judgment in the case of Uzma Manzoor and others v. Vice-Chancellor, Khushal Khan Khattak University, Karak, and others (2022 SCMR 694), this court held that while exploring and surveying the doctrine of legitimate expectation, “This doctrine connotes that a person may have a reasonable expectation of being treated in a certain way by administrative authorities owing to some consistent practice or an explicit promise made by the authority concerned,” says the written order.

The court noted that according to the lexicographers, the terms “domicile” and “residence” had been defined in the following context and perspective: I. Domicile 1, Black’s Law Dictionary (Ninth Edition), at page 558, “Domicile.” The location where a person has been physically present and considers “home”; a person’s true, fixed, principal, and permanent home, to which that person intends to return and remain even if they are currently residing elsewhere.

The word “domicile” is derived from the Latin “Domus,” meaning a home or dwelling house. Domicile is the legal conception of home, and the term “home” is frequently used in defining or describing the legal concept of domicile. Domicile is the relationship that the law creates between an individual and a particular locality or country.

“Domicile has also been defined as that place in which a person’s habitation is fixed, without any present intention of removing from that place, and that place is properly the domicile of a person in which he has voluntarily fixed his abode, or habitation, not for a mere special or temporary purpose, but with a present intention of making it his permanent home,” says the judgment.

“A legitimate expectation ascends in consequence of a promise, assurance, practice, or policy made, adopted, or announced by or on behalf of the government or a public authority,” the judgment maintained, adding that when such a legitimate expectation is obliterated, it affords locus standi to challenge the administrative action, and even in the absence of a substantive right, a legitimate expectation may allow an individual to seek judicial review of wrongdoing. In deciding whether the expectation was fair or not, the court may consider that the decision of a public authority has breached a fair expectation, and if it is proved, the court may annul the decision and direct the concerned authority/person to live up to the

“In the wake of the above discussion, we do not find any irregularity or perversity in the impugned judgments passed by the learned high court, and the civil petitions are therefore dismissed and leave is refused,” the judge concluded.

The petitioners have challenged the judgment of the Peshawar High Court, passed in W.P. No. 2932-P/2017, wherein the respondent/petitioner (Ms. Sonia Begum) applied for the post of a primary school teacher (PST)) (Female). During the appointment process, her name was placed at Serial No. 3 of the Merit List compiled for the Union Council (“UC”) Zayam, but she was refused appointment on the sole ground that, as per her Computerized National Identity Card (CNIC), she is not a permanent resident of the said UC, while according to her, she is the permanent resident of village Haji Noor, Muhammad Kalay, UC Zayam, and possesses a domicile of the same UC, but on her CNIC, the address of her mother’s village was mentioned, where her parents had only resided for two or three years.

After hearing the arguments, the learned high court remitted the petition to the District Education Officer (DEO) (female), Charsadda, with the direction to consider the respondent/petitioner for appointment against the post of PST at her UC strictly according to the guidelines provided in which the same high court had previously decided if the petitioner/respondent possesses the required qualification and merit position.

The petitioners have challenged the judgment of the Peshawar High Court wherein the respondent/petitioner (Ms. Shakila Chaman) applied for the post of PST with a Master’s Degree and PTC certificate. She qualified for the aptitude test conducted through NTC, and after qualifying for the test, her name was listed as Serial No. 8 of the Merit List, but she was dropped from the final list due to a difference between the address indicated in her domicile and her CNIC.

The respondent/petitioner asserted that she has a domicile in Tehsil Salarzai, and in her CNIC, the permanent address of Salarzai was shown, as well as in her Permanent Residence Certificate, even though she was dropped from the merit list.

-

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

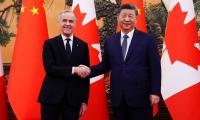

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training -

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light -

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push -

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down -

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career -

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer -

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis -

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI -

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds -

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years -

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome