What do the people think?

Lack of political polling in Pakistan means widely exaggerated claims and assessments about the street power of a political leader, incorrect predictions about elections and – most importantly – the government and the establishment taking widely unpopular and in fact contrary to public will decisions.

Polling is part and parcel of democratic setups across the world. If the democratic government is ‘by the will of people’, many would argue: how do we know the will of the collective nation, if not through polls? What is the political mood of the nation, known through scientific polling at the moment? This article wishes to shed light on some of the popular issues.

An issue that catches popular as well as media attention is which party is doing better than the others in public imagination and experience. Polling data from Gallup Pakistan suggests without doubt the PTI is riding on the back of a strong popular vote swing. Just before the vote of no-confidence the polling data suggested that the PTI and PML-N were neck and neck. A reminder: in the 2018 general elections, the PTI had 31 per cent support and the PML-N had 26 per cent support. The widely held assessment therefore before the VONC was also incorrect: the PTI was not widely unpopular; it had lost its edge and the PML-N had caught on to the PTI. Voting behaviour is such that the shifts are glacial; a critical and unhappy voter of a party withstands lots of hard times before switching.

Post-VONC, the PTI has at least an upswing in vote bank by an additional 7-8 per cent and most of this has shifted from the PML-N (which indirectly also means that this shift has happened in Punjab). There are many reasons for this surge in vote bank but the headline reasons are what can be classified as push and pull factors. Other party voters (these 7-8 per cent new entrants into the PTI vote bank) have been pushed away from their parties (chiefly, the PML-N) because the party has dwindled in its mass appeal: leadership is missing in action, second generation leaders’ mass appeal is limited especially for the 10 million plus middle class and graduate voter class who consider them not rightful leaders. Self-interested, corrupt and nepotistic (sharing power among their own family members) are other charges levied by those deserting these parties and joining the PTI.

Lastly, the old parties have lost their electoral narrative; the narrative has run its shelf life and whatever was left of it is better articulated by the PTI. The lack of fresh ideas in the narrative space is not just limited to these old parties. The PTI, despite its revolutionary tenor, in essence does not offer a whole lot new in the narrative space: anti-Americanism, Islamic state or Islam under threat, anti-India posturing are all tried and tested slogans. The new narratives for political parties in Pakistan, and lack thereof, are possibly reflective of a wider disenchantment and perhaps loss in the plot in the larger story of Pakistan.

One way of reading these changes in the political environment is that there is increasingly a space for a new political party in Pakistan which can offer a fresh narrative and raise a new political slogan. The 2023 general elections may not see new parties breaking in but it is quite obvious that the 2028 general elections would see major changes in the electoral space in the country.

What is the standing of other state institutions in the public’s opinion? The major finding here is that, despite a major bulge in support for the PTI, the other institutions of the state are also popular and hold sway in the public imagination. On the one hand, despite all their faux paus, civilian institutions have been gaining respectability since the mid-2000s in Pakistan and net positive ratings have been given by Pakistanis in our polls. These institutions are represented by the National Assembly and political parties in general. Some of this pro-civilian government fervor is what the PTI has been able to cash in on.

The other institution doing well in public imagination is the superior judiciary. Again, the respectability gained by the superior judiciary through the Chaudhry Iftikhar court and its very public and bold stand for issues directly confronting the public has continued and was further bolstered by the Saqib Nisar Court. Currently, after the military, the Supreme Court has the highest approval rating among the pillars of the state with as high as 70 per cent having trust in them (the lower judiciary has very low approval rating as reflected in the WJP Index released every year).

Lastly, the military in Pakistan has traditionally been a popular and loved institution. In the recent stand-off between the military and the PTI and not so long ago between the military and the PML-N, some have argued for a major reduction in ratings for the army. The public opinion polls in recent months paint a more nuanced picture. In a recent survey done only a few weeks ago, as high as 90 per cent Pakistanis, including supporters of all political parties, said that they loved the Pakistan Army. Similarly, there is widespread dissatisfaction with the public naming of serving generals by politicians: 2 in 3 Pakistanis disapproved of PTI Chief Imran Khan naming an army official as an accused in his attack.

Having said this, the needle has indeed moved with respect to popular public opinion supporting the military to remain restricted to their role as guardians of the borders and leaving politics and economy to the civilians. More importantly, at the elite level the support for civilian vs military rule has significantly moved in favour of the civilians. Overall a significant majority in Pakistan would like to avoid major confrontation between politicians and the structures of the state. Even a very popular politician like Imran Khan would therefore find himself in a difficult spot with the everyday voter in taking a confrontational posture against the establishment.

Lastly, the public mood about the national political and economic weather is a mix of anxiety and lack of direction. The recent months of economic turmoil (highest inflation in Pakistan’s history,) floods of massive size engulfing and affecting one in three Pakistanis and then the change of governments (in Punjab, three changes in three months) has made the people think about the future of the country. In a recent survey of businesses in Pakistan, 8 out of 10 businesses felt that the direction of the country was wrong and almost 6 in 10 reported a bad economic situation. Hope is a major casualty in this tug of war at the national political stage.

Pakistan has seen many ups and downs and therefore this current impasse will eventually go away too. However, every crisis increasingly takes away the hope that Pakistanis have in a prosperous future for the country and for their children. Politicians as well as other institutions have until now used the renewed trust people have put in them for their own corporatist interests. One very much hopes that sooner rather than later our leaders do justice to the trust citizens place in them.

The writer is a graduate of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London and heads Gallup Pakistan.

-

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss -

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning -

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding -

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border -

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene -

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce -

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All'

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All' -

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals -

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked -

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

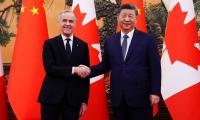

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training