HEALTH

More and more essential medicines are disappearing from market as government-industry pricing row stands unresolved

Quality healthcare is the basic right of the citizens and it is the responsibility of the state to ensure an environment where they get it without much hassle. The state is also supposed to provide affordable healthcare to its people and, in the case of private healthcare sector, set up a regulatory framework that minimises or puts an end to any chances of exploitation and foul play. Another important duty of the state is to ensure supply of affordable and quality medicines in the market and promote a culture of advanced research in the field of curative medicine.

Quality healthcare is the basic right of the citizens and it is the responsibility of the state to ensure an environment where they get it without much hassle. The state is also supposed to provide affordable healthcare to its people and, in the case of private healthcare sector, set up a regulatory framework that minimises or puts an end to any chances of exploitation and foul play. Another important duty of the state is to ensure supply of affordable and quality medicines in the market and promote a culture of advanced research in the field of curative medicine.

In Pakistan, the situation is that the government-run hospitals and healthcare facilities like the Basic Health Units (BHUs) are generally not up to the mark and the patients have to rely primarily on the private sector. The overall cost of private medical treatment that may include physician’s fee, cost of laboratory tests, room charges at hospitals, surgery fee, medicine prices, etc, is quite high, especially when compared with the average earning capacity of the people. Therefore, it is understandable and often advised that the government must regulate this sector and make interventions wherever required.

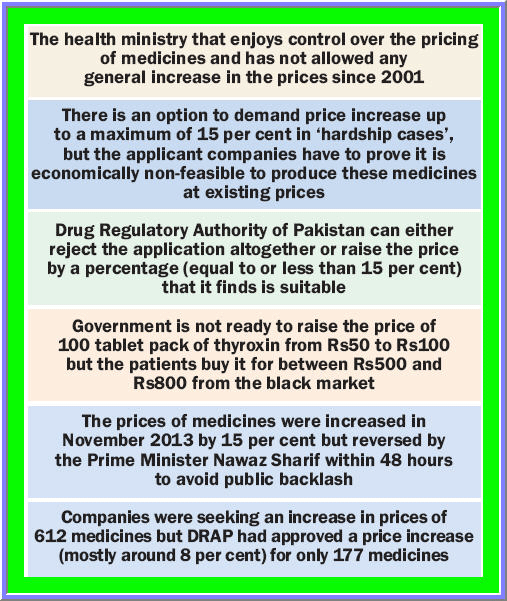

However, over the last many years a standoff between the government and the pharmaceutical companies has created some problems for the patients, industry and the regulators. The issue at hand is the health ministry that enjoys control over the pricing of medicines and has not allowed any general increase in the prices since 2001.

Though there is an option of demanding price increase up to a maximum of 15 per cent in “hardship cases,” the applicant companies have to prove that it is economically non-feasible for them to produce these medicines at existing prices. The Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP) can either reject the application altogether or raise the price by a percentage (equal to or less than 15 per cent) that it finds is suitable. Most of the cases decided recently in the favour of the companies have seen price increase of around eight per cent.

No doubt, it is more than an ideal situation for the people, but the question is are there any other commodities that have faced price cap for 15 years; and can the pharmaceutical industry survive in such a scenario, asks Khalid J Chaudhry, Chairman, Medipak Group. The cost of petrol, diesel, electricity, raw material, labour, land, construction, maintenance, etc, has skyrocketed in the last 15 years, but the government still wants the industry to stick to the decades-old prices, he adds. Another negative, he says, is that the cash-strapped and non-viable companies due to this price cap cannot invest at all in research and development.

He complains that many medicines are out of production due to their non-viability, and instead smuggled and substandard medicines are filling the demand and supply gap. It is a pity, he says, that the government was not ready to raise the price of 100 tablet pack of thyroxin from Rs50 to Rs100 but the patients had to buy it for between Rs500 and Rs800 from the black market. “It seems the government is convinced that this industry is not affected by inflation and the rise in the cost of doing business.”

The latest issue is that of the tuberculosis (TB) drugs that are extremely short in the market and the main reason is that most of the companies producing them in Pakistan have suspended their production. The only ones producing them at the moment are also in problems and if they quit there will be a crisis in Pakistan that is currently ranked as a country having the eighth largest population of TB patients.

The shortage of certain medicines, including cough syrups and remedies for psychiatric patients, caused by delay in release of narcotics quota by the government adds to the intensity of the problem. After the notorious ephedrine quota scandal, it is the industry that has had to suffer due to strict controls on release of narcotics that are used as raw material in their products.

There are allegations as well that the government simply wants to gain political mileage by twisting the arm of the pharmaceutical industry. The critics claim it has failed miserably to control the cost of medical consultancy and services as well as smuggling and counterfeiting of medicines. The prices of medicines were increased in November 2013 by 15 per cent but reversed by the Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif within 48 hours to avoid public backlash. It was around one per cent raise per year if calculated over a period of 15 years.

Anyhow, the critics of the pharmaceutical industry are also there who claim the profit margins of the medicine companies are quite high even in the current scenario. “They warn of bankruptcy on one hand and on the other take doctors and their families on international pleasure trips. They also spend a lot on renovation of their private clinics and give them expensive gifts. All they want in return is that these doctors shall prescribe medicines of their company to their patients,” alleges Ahmad Raza, a social worker living in northern Lahore.

Anyhow, the critics of the pharmaceutical industry are also there who claim the profit margins of the medicine companies are quite high even in the current scenario. “They warn of bankruptcy on one hand and on the other take doctors and their families on international pleasure trips. They also spend a lot on renovation of their private clinics and give them expensive gifts. All they want in return is that these doctors shall prescribe medicines of their company to their patients,” alleges Ahmad Raza, a social worker living in northern Lahore.

Ayesha Tammy Haq, Executive Director, Pharma Bureau Pakistan-a body of multinational pharmaceutical companies operating in the country states that only those medicines go out of production whose prices fixed by the government are far lower than their very cost of production.

She says that with the escalation of input cost over the last one and a half decades the companies have tried all they could to continue production of such medicines. “We compromised on the quality of packing, removed accessories like plastic spoons and measuring cups etc to cost cuts but now there is no option left.”

Ayesha says they were even advised to decrease the volume of medicines in the packing to cover the loss but this suggestion was ruled out as it was against business ethics and their head offices would also object to it. “The MNCs are extremely touchy about their reputation and cannot put it to stake by resorting to such tactics.”

On the shortage of TB drugs, she explains that out of the 18 companies that produced these all but two have stopped their production and the reason once again is “the unjustified price control.” She says the prices of medicines were fixed at a time when a US dollar was equal to 60 Pakistani rupees. Today despite escalation of 80 per cent in this exchange rate in favour of the dollar, there is no support for the sector, she adds. “Exchange rate is vital as most raw material is imported.”

Ayesha insists that Pakistan government must prepare a list of essential medicines approved by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and ensure their regular supply in the market at any cost. It can keep prices in control by offering subsidy or other incentives to the manufacturers and transfer to the consumers.

But, on the other hand, she says, it must withdraw from the unnecessary price control and let the market flourish. “When new companies will enter there will be competition. Prices will come down and the quality will improve. At the moment investors are wary due to the 15 years old price cap and the unnecessary state interference. “If there is no profit, who will be willing to invest?”

Ayesha states that none of the companies she represents, lavishly spend money on doctors and their families or take them abroad on pleasure trips. If somebody is found involved in such activities, strict disciplinary action is taken against him and his company, she clarifies. However, she says, selective doctors are taken abroad to attend international conferences on new research, therapies, medicines, etc, so that they can update their knowledge and serve their patients better than before.

Ayesha states that none of the companies she represents, lavishly spend money on doctors and their families or take them abroad on pleasure trips. If somebody is found involved in such activities, strict disciplinary action is taken against him and his company, she clarifies. However, she says, selective doctors are taken abroad to attend international conferences on new research, therapies, medicines, etc, so that they can update their knowledge and serve their patients better than before.

The facts stated by the pharmaceutical companies have been corroborated by the Minister of State for National Health Services Saira Afzal Tarar. She informed the Senate on June 7, 2016 that the companies were seeking an increase in prices of 612 medicines but DRAP had approved a price increase (mostly around 8 per cent) for only 177 medicines.

All said, the point to stress is that the stakeholders including the industry and the government shall reach an arrangement where the interests of citizens are not compromised and neither does the industry become economically unviable. Examples of other countries in the region that have faced similar challenges and overcome these can also be followed. But the most important point is that all this shall be done on a priority basis and without further dilly-dallying as it is a matter of health and life.

The writer is a staff member