Traditional Pashtun music stages a comeback as security improves

Pashtun music is characterised by rabab, Central Asian stringed instrument, played to the beat from tablas

Peshawar: For years the distinctive twang of Pashtun music was drowned out by rattling gunfire and deafening explosions in Pakistan's northwest. But, as security improves, a centuries-old tribal tradition is staging a comeback.

Performances that once took place in secret are returning. Shops selling instruments are open and thriving again, while local broadcasters frequently feature rising Pashto pop singers in their programming.

And new, up and coming bands like Peshawar's Khumariyaan have reached rare, nationwide acclaim after appearing on the popular Coke Studios broadcast, where they fused traditional sounds with modern tastes — spreading Pashtun music far from its native homeland.

"Music is the spice of life... it has been a part of our culture from time immemorial," says Farman Ali Shah, a village elder and Pashto poet in Warsak village near Pakistan's tribal areas in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

Pashtun music is characterised by the rabab, a Central Asian stringed instrument, played to the beat from tablas drums, with songs salted with florid lyrics describing the pain of unrequited love or calls for political revolution.

"For centuries we were a liberal society," explains rabab player and member of the National Assembly Haider Ali Khan from Pakistan's Swat Valley.

"We love our religion but at the same time we love our traditional music."

Yet the slow creep of extremism had been threatening that tradition for decades.

Beginning in the 1970s more extremist movements started gaining influence in the Pashtun areas along the border with Afghanistan, promoting dismissive takes toward music.

"The extremists were killing artists and singers in the society to create fear," explains singer Gulzar Alam, who was attacked three separate times and later left Pakistan, fearing for his life.

"If you remove the culture from a community, tribe, or ethnic group the community will be eliminated."

Public performances were all but halted as waves of suicide bombers unleashed havoc.

CD markets were bombed, instrument shops destroyed, and musicians were intimidated or either outright targeted.

Singers and musicians fled en masse, while others were gunned down.

A brave few continued to invite musicians to play in private shows at hujras and weddings, albeit without large sound systems that could possibly attract outside attention.

"They were asking people to stop music but villagers never accepted them," says Noor Sher from Sufaid Sang village, where his family has been making rababs by hand for 25 years.

Amid the chaos the art form was also maintained thanks to increasing numbers of Afghan musicians also fleeing violence in their own country who resettled in places like Peshawar, opening music schools that kept the tradition alive.

-

Melissa Joan Hart reflects on social challenges as a child actor

-

'Gossip Girl' star reveals why she'll never return to acting

-

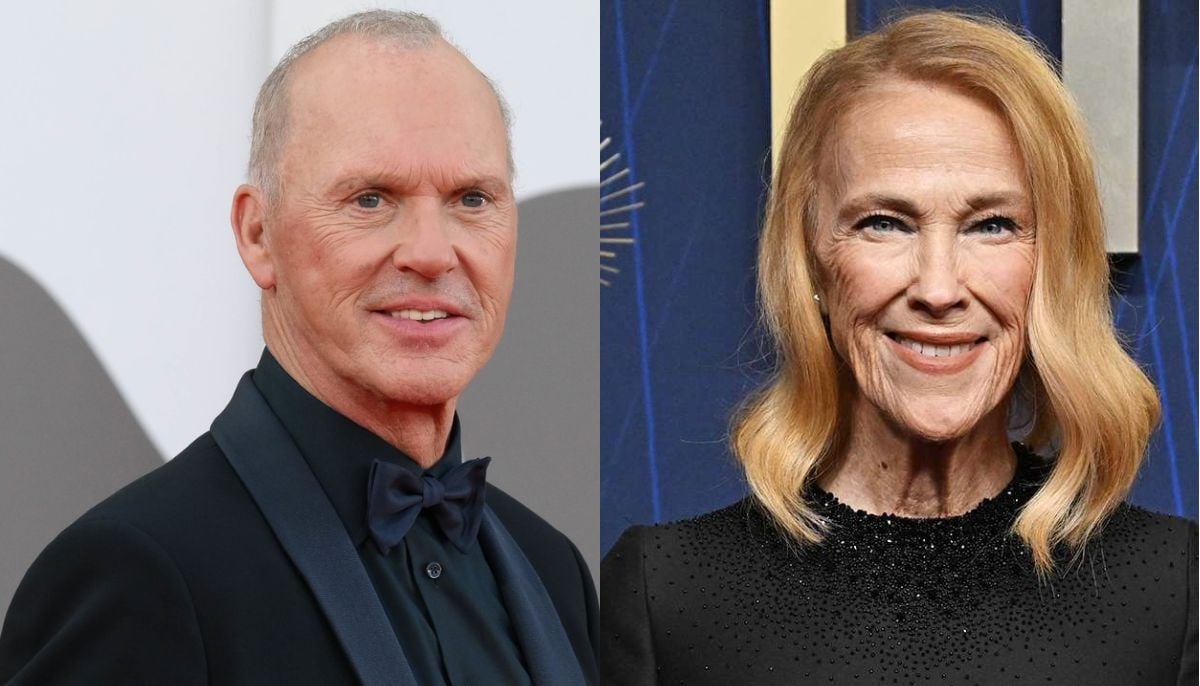

Michael Keaton recalls working with Catherine O'Hara in 'Beetlejuice'

-

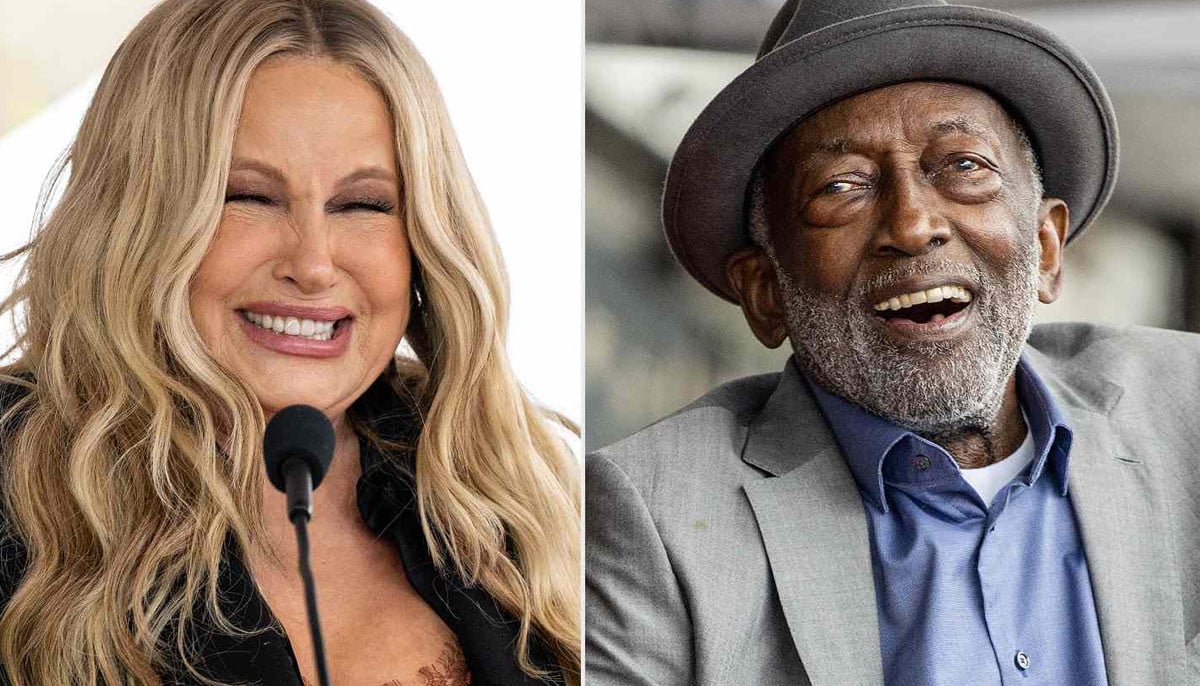

Carmen Electra says THIS taught her romance

-

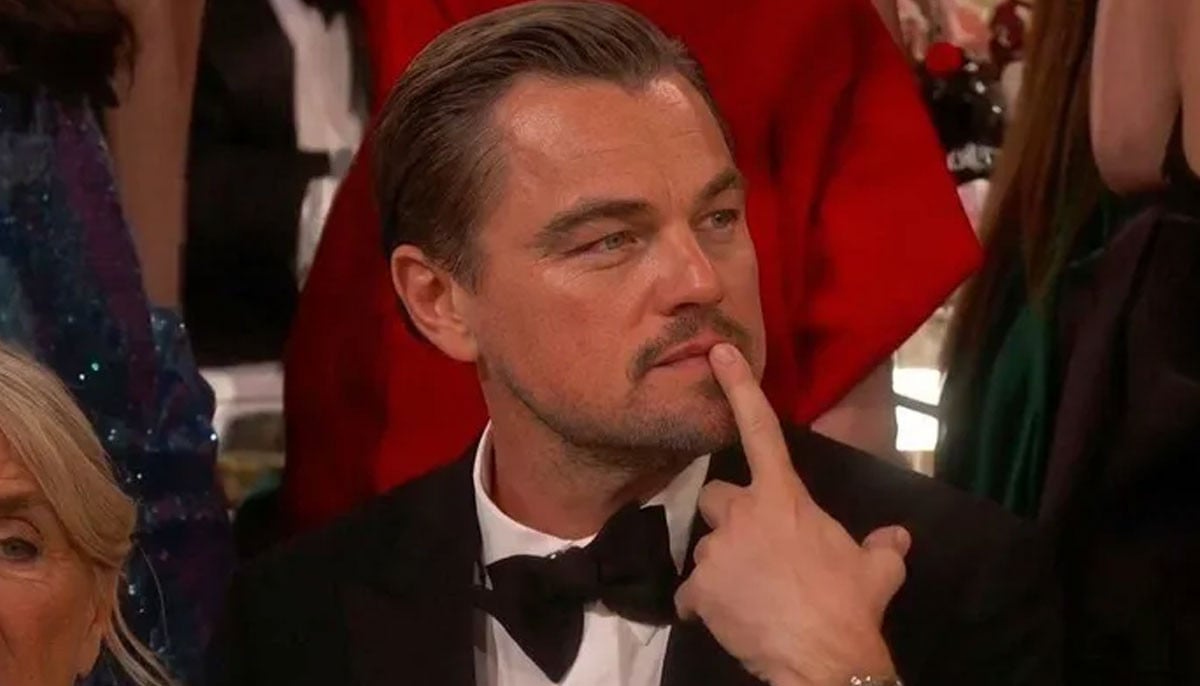

Leonardo DiCaprio's co-star reflects on his viral moment at Golden Globes

-

J. Cole brings back old-school CD sales for 'The Fall-Off' release

-

Why is Thor portrayed differently in Marvel movies?

-

DC director gives hopeful message as questions raised over 'Blue Beetle's future