As it were this time last year, grey clouds are hovering over Merewether Tower as the clock strikes 12 in the afternoon. Buses, cars and motorbikes halt for a group of pedestrians trying to cross the busy thoroughfare, II Chundrigar Road, to reach the decades-old Edhi Centre in Mithadar.

With the passing of Pakistan’s greatest philanthropist, Abdul Sattar Edhi, on July 8 last year, the centre like all others is now looked after by his son Faisal Edhi, while one of the foundation’s longest serving representatives, Anwar Kazmi, sits in the office managing the day-to-day activities.

Clad in a grey shalwar kameez, he sits behind a desk teeming with stacks of files and two telephone sets that ring almost incessantly. Kazmi, 72, had known Edhi since 1962 when he took a friend to the Mithadar dispensary.

“Edhi called for a compounder to tend to my friend, while he sat down on a bench and spoke to the rest of us for a long time. We discussed local and world politics; I was quite politically charged at the time and was associated with the left. Over the course of that conversation, it turned out that we shared similar thoughts and he asked me to come by more often. That was the start of a bond that lasts to this day,” he reminisced.

Referring to the famous strike by students in 1964 near DJ Science College in which many were injured, he said Edhi had stepped in personally at the time to tend to the victims. “We had to strategise because had we taken those students to the civil hospital they would have been booked by the police. So we took them straight to Edhi sahab who tended to the injured.”

“Our friendship grew stronger because of our like-mindedness and finally in 1970, I started working with the Edhi Foundation; at the time, though, the foundation was much smaller in scale as compared to what we see today.”

Speaking about the late humanitarian, Kazmi said that Edhi’s four core principles – simplicity, truthfulness, hard work and punctuality – were what catapulted him to greatness. “His thoughts always translated into actions. Also, I don’t remember him ever mincing his words; he couldn’t care less about repercussions.”

Against the tide

When Edhi pursued his mission, he was going against the norms of his community, said Kazmi.

“He told the Memon community that he only wanted to work for humanity and wasn’t interested in the dynamics of any particular community system, solely because they were controlled by men seeking profits. He said he didn’t want to pave the way for those who would always be needy.”

Known for his journey from an 8x8 dispensary to one of the world’s largest humanitarian organisations, Edhi had told the world that he would not seek donations because he was sure that common people would come forward to help him when they saw his efforts.

“The people did help him. When they saw his tireless work ethic, they came forward in droves to donate. It was with their assistance that after a few years Edhi acquired a second-hand vehicle that he transformed into an ambulance. At the time that was our only ambulance and it went all over the city to help people in distress,” Kazmi narrated.

Faith and fury

Though he was considered a man of few words who had an impassive expression, Kazmi recalled a time when he saw Edhi immensely angry.

“One of the worst tragedies to have occurred in Karachi was the 1987 bombing in Bohri Bazaar, the first of its kind in the city. I was sitting with Edhi when the news started filtering in; within minutes calls were made to all units of the city and all ambulances were told to rush to the scene.”

Kazmi recalled that all vehicles were soon out in the field, except for one that remained parked at the centre. “We found out that the ambulance driver had gone to say his prayers. I seldom saw Edhi sahab as upset as he was when we told him the reason; he was incensed that the driver had chosen to go for prayers instead of helping those battling for their lives. His words at the time were, “Any man who can’t understand the essence of humanity cannot work with us”.”

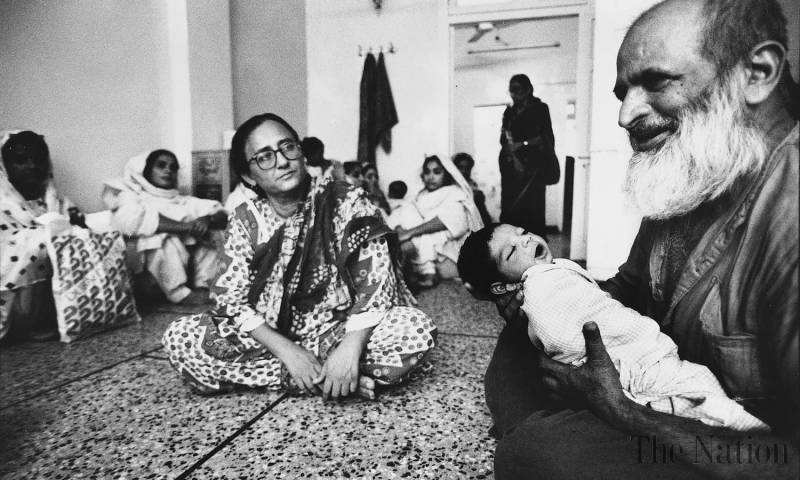

A motorcyclist (R) pays his respects to Abdul Sattar Edhi (2nd L), as he travels to his office in Karachi.

He had also once called out the military dictator, General Zia-ul-Haq, for giving room to religious fanaticism, urging him to instead provide basic necessities for the people.

“At the time, Edhi sahab spoke at a well-attended event and told all those present that neither did Pakistan need enforcement of religious laws nor did the people want it. He said the villages needed more schools and hospitals, not mosques and madrasas. The criticism against him after this speech was instantaneous but Edhi never did back down from voicing his opinion,” said Kazmi.

Ignoring naysayers

It is hardly a secret that there was a widespread propaganda campaign against Edhi owing to his secular notions.

“He was called ‘chanda khor’, ‘dehriya’, and other such names but he never responded to anyone. We were young and always itching to give a rebuttal but he said ‘apna rasta khota na karo (don’t add obstacles in your own path)’,” Kazmi laughed.

Instead, he added, Edhi would always refer to an example of a beggar entering a village. “He would say that a beggar carries a stick with himself to ward off stray dogs. If a dog comes too close, he just waves the stick to make it step back. Similarly if they would come near me I will signal them with the stick because I can’t let them impede my path. If the beggar would waste his efforts in fighting all the dogs, he wouldn’t be able to survive.”

Passing the mantle

Over the course of the year that has passed since Edhi’s demise, many questioned the capability of his son, Faisal Edhi, to pick up where his esteemed father left off.

“He raised Faisal to one day fill his shoes. Ever since his childhood, Faisal accompanied his father on relief work. He knew he would depart one day and while Edhi sahab is undoubtedly irreplaceable, he moulded Faisal in way that I am sure he would prove his mettle in a few years.”

“Yaar it only takes a minute, get more of them”

Recalling the time when the charity foundation’s communications system was being transformed into a wireless one, a visibly amused Kazmi said Edhi had stopped talking to him owing to their disagreement over the new system.

Faisal Edhi

“Edhi sahab was reluctant because he feared it would be costly and useless. We would be sitting right next to each other but he grew silent on me and refused to come near the vehicles after the system was installed. Finally, a Sri Lankan engineer took him to test the system and from the Tower centre Edhi was able to connect with the volunteers in different areas of the city. When he found himself speaking to Haji Iqbal from Moosa Lines or Raju in Korangi, Edhi sahab started laughing and turned to me and said, ‘Yaar, it only takes a minute, get more of them’.”

He said Edhi’s chief concern was that public money would be wasted on what he thought would be a huge investment. “To our luck, the person who took up the task felt he was indebted to Edhi sahab because he had found his intellectually disabled daughter through an Edhi home.”

‘I can’t dodge a bullet with my name on it’

Going back to the time when the army patrolled the streets of Karachi, Kazmi said an incident in Aligarh Colony made them take the risk of venturing out during curfew time.

“Nobody was stepping out because of the volatile situation in the city during the 90s. When we received the news about shootout and that causalities were feared, Edhi sahab and I headed to Aligarh Colony.”

“Soon, security personnel intercepted us and told us we could not proceed further. We tried to reason with them and, finally, a senior officer who recognised Edhi sahab told the men to let us through. It was a fierce clash between Mohajirs and Pakhtuns but both sides stopped as soon as we entered the area.”

“That was the kind of risk Edhi sahab was always willing to take. There were times when even we would advise him against a certain plan. However, his reply was always the same; if a bullet is fired with my name on it, no force on earth can divert it elsewhere.”