VIDEO: Nasa's Hubble telescope discovers water vapour on small exoplanet which may host life

"Water on a planet this small is a landmark discovery," says astronomer

The tiniest exoplanet whose atmosphere has been found to contain water vapour, was studied by astronomers using Nasa's Hubble Space Telescope.

GJ 9827d, a planet with a diametre only slightly larger than Earth, may serve as a model for other planets in our galaxy that have atmospheres rich with water, according to NASA Science.

"This would be the first time that we can directly show through an atmospheric detection, that these planets with water-rich atmospheres can actually exist around other stars," said team member Björn Benneke of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets at Université de Montréal. "This is an important step toward determining the prevalence and diversity of atmospheres on rocky planets."

"Until now, we had not been able to directly detect the atmosphere of such a small planet. And we're slowly getting in this regime now.

"At some point, as we study smaller planets, there must be a transition where there's no more hydrogen on these small worlds, and they have atmospheres more like Venus (which is dominated by carbon dioxide), Benneke added.

Meanwhile, co-principal investigator of Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, Laura Kreidberg said that water on a planet this small is a landmark discovery.

"It pushes closer than ever to characterising truly Earth-like worlds," she added.

However, it is yet too early to determine, though, whether the planet's atmosphere is primarily composed of water, left over from a primordial hydrogen/helium atmosphere that evaporated under the influence of stars, or whether Hubble spectroscopically detected a tiny quantity of water vapour in a puffy hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

"Our observing program, led by principal investigator Ian Crossfield of Kansas University in Lawrence, Kansas, was designed specifically with the goal to not only detect the molecules in the planet's atmosphere, but to actually look specifically for water vapour," said the science paper's lead author, Pierre-Alexis Roy of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets at Université de Montréal.

"Either result would be exciting, whether water vapour is dominant or just a tiny species in a hydrogen-dominant atmosphere," he said.

At eight hundred degrees Fahrenheit, the planet is as hot as Venus, thus if the atmosphere consisted mostly of water vapour, it would undoubtedly be a hostile and muggy place.

-

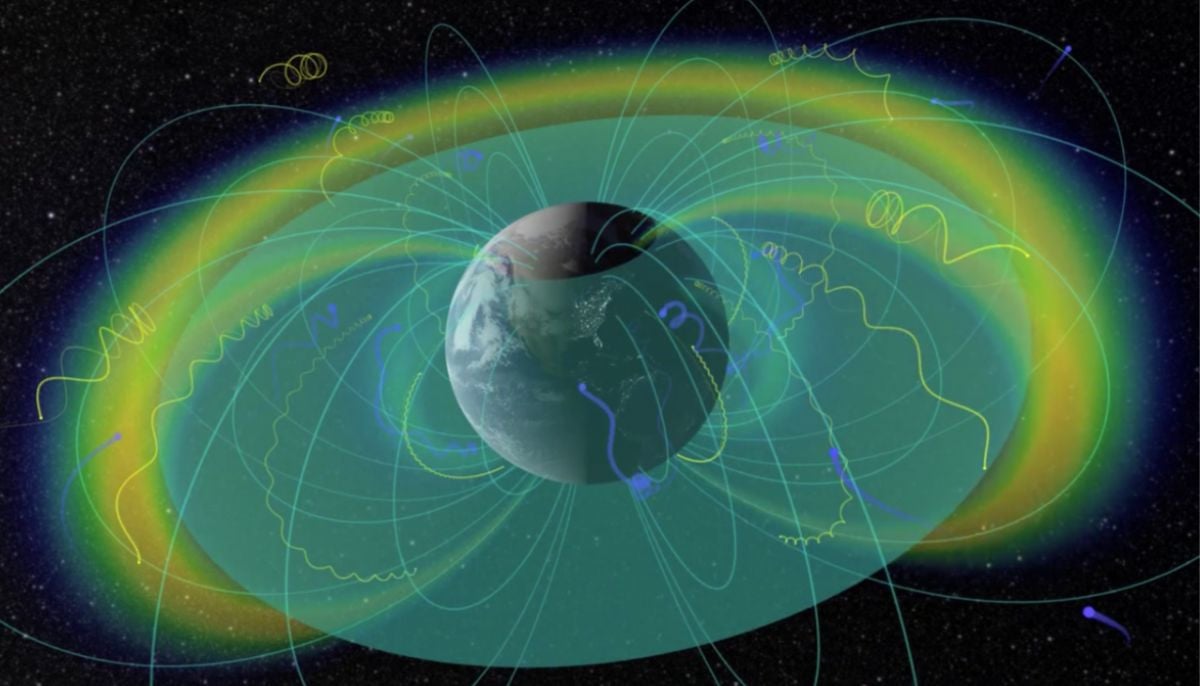

‘Smiling electrons’ discovered in Earth’s magnetosphere in rare space breakthrough

-

Archaeologists unearthed possible fragments of Hannibal’s war elephant in Spain

-

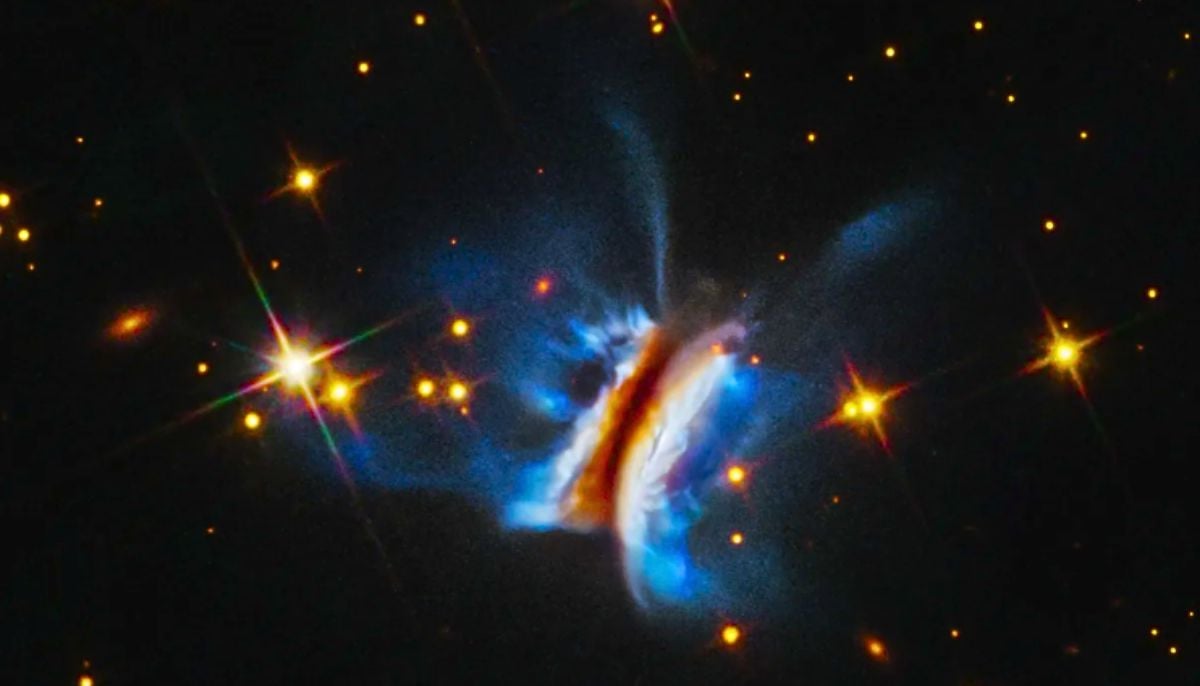

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope discovers ‘Dracula Disk', 40 times bigger than solar system

-

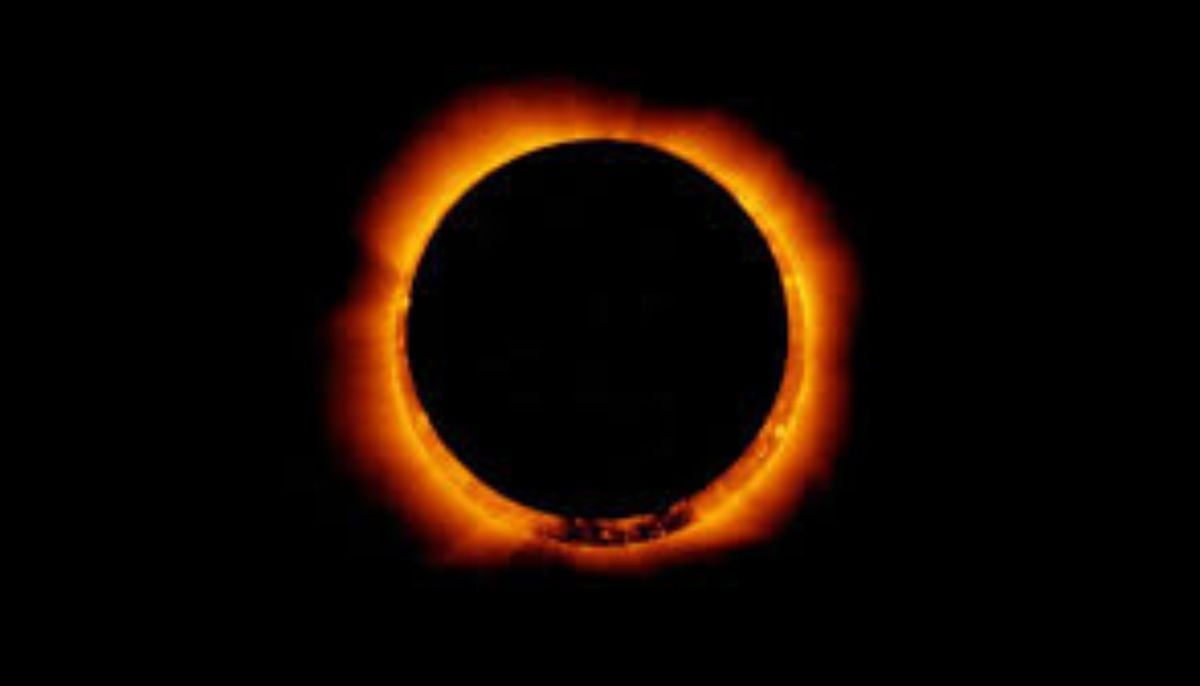

Annular solar eclipse 2026: Where and how to watch ‘ring of fire’

-

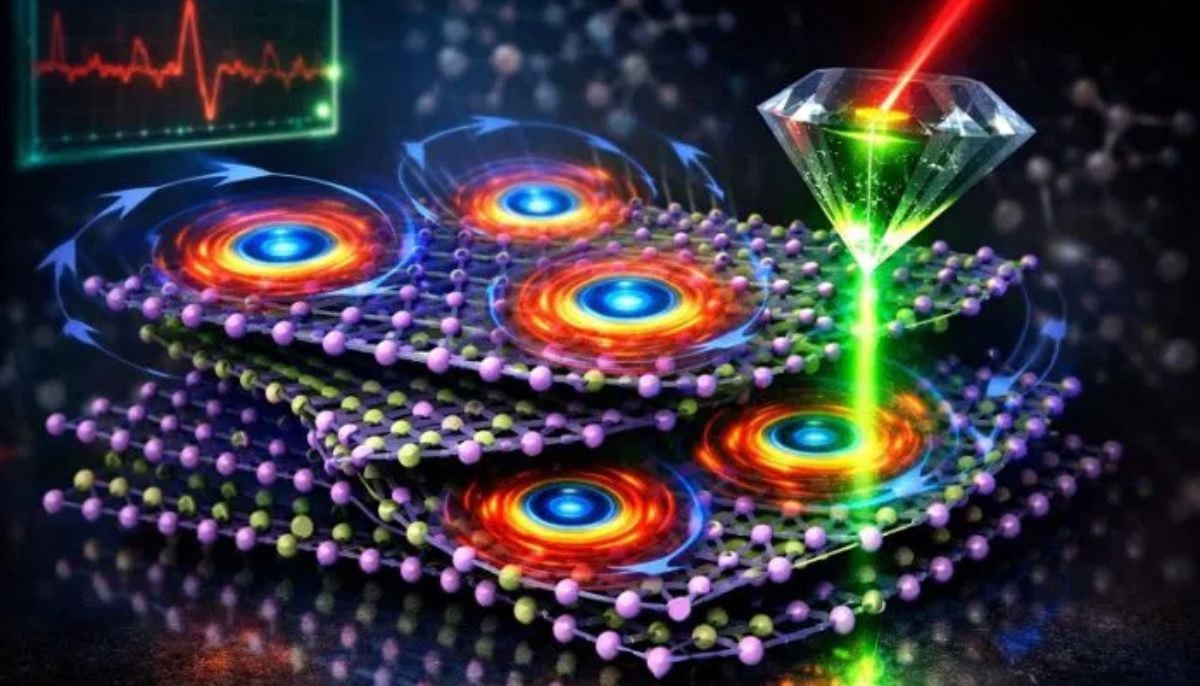

Scientists discover rare form of 'magnets' that might surprise you

-

Humans may have 33 senses, not 5: New study challenges long-held science

-

Northern Lights: Calm conditions persist amid low space weather activity

-

SpaceX pivots from Mars plans to prioritize 2027 Moon landing