Origin of life on Earth not a mystery anymore as part of 1.75b years old code cracked

Small truth about photosynthesis aids scientists in solving mystery behind origin of life on Earth

Researchers on a mission to understand the origins of life just learned a small lesson about photosynthesis from 1.75 billion years ago.

According to a team of academics' recent study published in Nature, microfossils discovered in north Australia's desert exhibit the earliest known evidence of photosynthesis, which might lead to a deeper comprehension of the possible origins of life itself as per Popular Mechanics.

These microfossils are the remains of cyanobacteria, an organismal class that may have existed for up to 3.5 billion years, according to researchers (albeit the earliest fossil examples are from about 2 billion years ago).

Some of these species may have been able to contribute enormous amounts of oxygen to Earth's atmosphere through photosynthesis during the Great Oxidation Event because, at some point in their evolution, they developed thylakoids, which are structures within cells where photosynthesis takes place.

The earliest evidence of photosynthesis discovered to date is provided by these new findings. According to the researchers, these earliest photosynthesising cells formed some 1.75 billion years ago, and their discovery extends the fossil record by at least 1.2 billion years.

“[This discovery] allows the unambiguous identification of early oxygenic photosynthesisers and a new redox proxy for probing early Earth ecosystems,” the authors wrote in the paper, “highlighting the importance of examining the ultrastructure of fossil cells to decipher their paleobiology and early evolution.”

-

Sun appears spotless for first time in four years, scientists report

-

SpaceX launches another batch of satellites from Cape Canaveral during late-night mission on Saturday

-

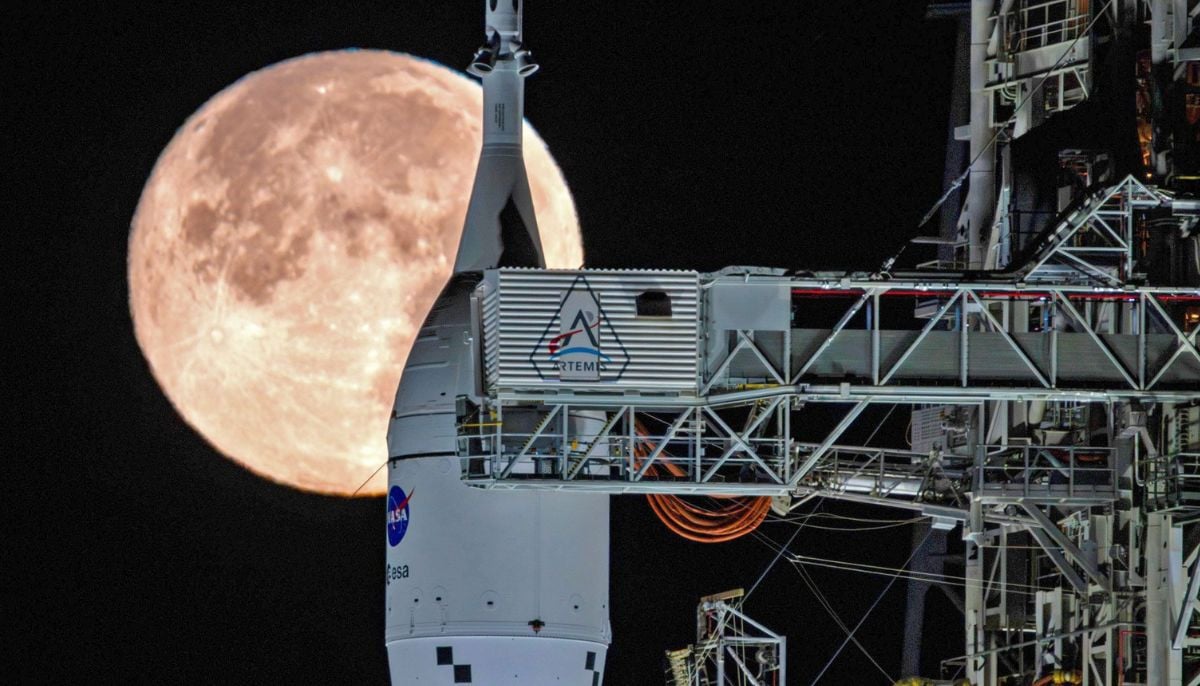

NASA targets March 6 for launch of crewed mission around moon following successful rocket fueling test

-

Greenland ice sheet acts like ‘churning molten rock,’ scientists find

-

Space-based solar power could push the world beyond net zero: Here’s how

-

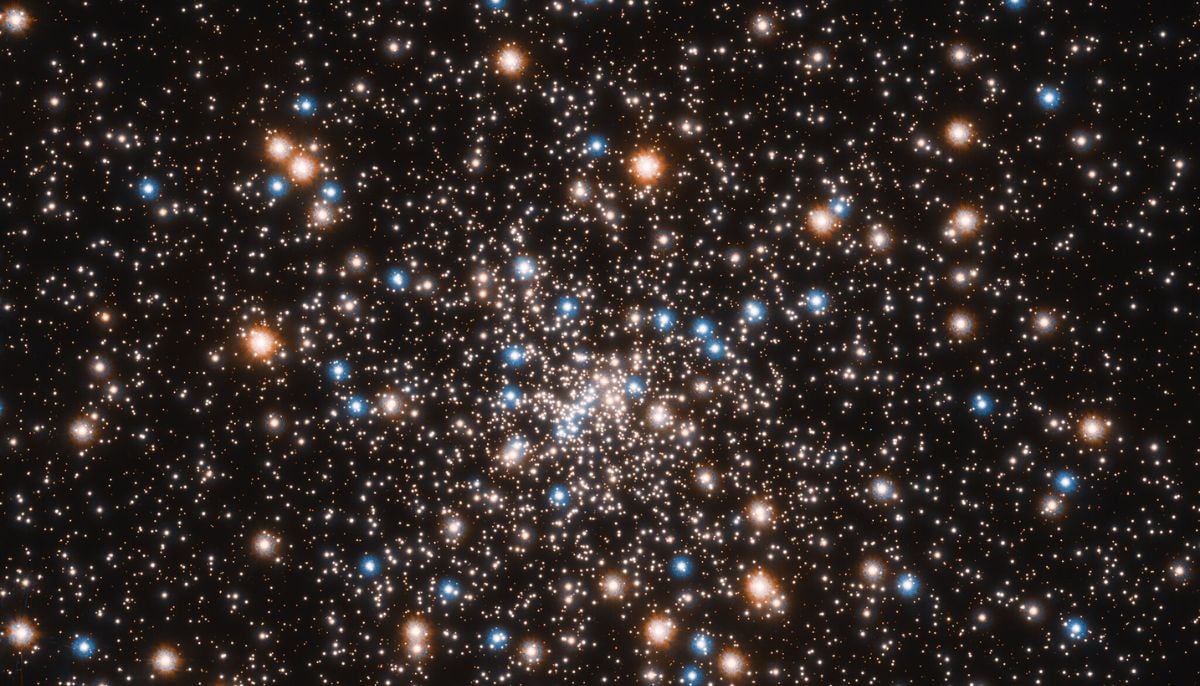

Hidden ‘dark galaxy' traced by ancient star clusters could rewrite the cosmic galaxy count

-

Astronauts face life threatening risk on Boeing Starliner, NASA says

-

Giant tortoise reintroduced to island after almost 200 years