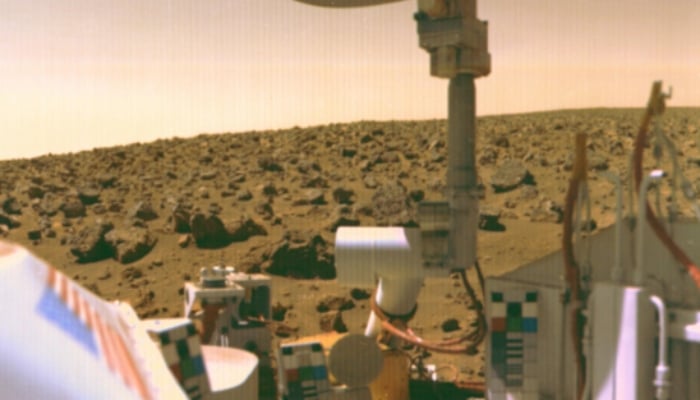

Did Nasa's 1976 Viking mission accidentally erase Martian life?

Researcher says experiments might have unintentionally eradicated microbes residing within Martian rocks

A scientist has claimed that Nasa might have accidentally eradicated signs of life on Mars nearly half a century ago.

However, the scientific community remains divided on whether these new claims are a speculative fantasy or a compelling potential explanation for certain past experiments.

In a June 27 article for Big Think, Dirk Schulze-Makuch, an astrobiologist at Technical University Berlin, proposed that after landing on the Red Planet in 1976, Nasa's Viking landers could have collected minuscule, resilient life forms hidden within Martian rocks.

If these extremophiles did or still do exist, the experiments carried out by the landers might have inadvertently terminated them due to the tests overwhelming these potential microbes, as outlined by Schulze-Makuch.

He acknowledges that this suggestion may provoke controversy but points out that similar extremophiles thrive on Earth and could theoretically inhabit Mars.

Nevertheless, other scientists argue that the results from the Viking missions are less enigmatic than Schulze-Makuch and others suggest.

The Viking landers, comprising Viking 1 and Viking 2, conducted four experiments on Mars:

- The Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (GCMS) experiment, sought organic, carbon-containing compounds in Martian soil.

- The labelled release experiment, tested for metabolism by introducing radioactively traced nutrients to the soil.

- The pyrolytic release experiment, examined carbon fixation by potential photosynthetic organisms.

- The gas exchange experiment, assessed metabolism by monitoring changes in key life-related gases, such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen, in isolated soil samples.

The outcomes of the Viking experiments proved perplexing and have continued to confound some scientists. The labelled release and pyrolytic release experiments yielded results hinting at the possibility of life on Mars, with small changes in gas concentrations suggesting some form of metabolism.

The GCMS also detected traces of chlorinated organic compounds, initially attributed to contamination from Earth-based cleaning products (subsequent missions confirmed the natural occurrence of these compounds on Mars).

However, the gas exchange experiment considered the most critical of the four, produced negative results, leading most scientists to conclude that the Viking experiments did not detect Martian life.

In 2007, Nasa's Phoenix lander, the successor to the Viking landers, discovered traces of perchlorate, a chemical found in fireworks, road flares, explosives, and some Martian rocks.

The general scientific consensus is that the presence of perchlorate and its byproducts can account for the gases detected in the original Viking results, effectively resolving the Viking dilemma, as explained by Chris McKay, an astrobiologist at Nasa's Ames Research Center in California.

Schulze-Makuch, however, suggests that the experiments may have produced skewed results due to the excessive use of water. He argues that since Earth is a water-rich planet, adding water to the Martian soil might have encouraged life to manifest in the extremely arid Martian environment. In retrospect, this approach might have been overly generous.

On Earth, arid environments like the Atacama Desert in Chile host extremophilic microbes that thrive by residing within hygroscopic rocks, which absorb minute amounts of ambient moisture. Mars also contains such rocks and possesses a level of humidity that could theoretically support similar microbes.

If these microbes contained hydrogen peroxide, a substance compatible with certain Earth-based life forms, they could have further facilitated moisture absorption and contributed to the gases detected in the labelled release experiment, Schulze-Makuch theorises.

Nevertheless, an excess of water can be fatal to these tiny organisms. A 2018 study in the journal Scientific Reports revealed that extreme floods in the Atacama Desert killed up to 85% of indigenous microbes incapable of adapting to wetter conditions.

Thus, adding water to potential Martian microbes in the Viking soil samples might have been akin to stranding humans in the middle of an ocean. Both organisms require water for survival, but in incorrect concentrations, it can be lethal to them, according to Schulze-Makuch.

Alberto Fairén, an astrobiologist at Cornell University and co-author of the 2018 study, concurs, suggesting that adding water to the Viking experiments could have terminated potential hygroscopic microbes and contributed to the contradictory results observed.

It's worth noting that this is not the first time scientists have proposed that the Viking experiments might have inadvertently eradicated Martian microbes. In 2018, another group of researchers posited that heating soil samples could have triggered an unexpected chemical reaction, potentially incinerating any microbes within the samples.

Nevertheless, as McKay argues, some scientists continuing to question the results of the Viking missions might be pursuing a futile endeavour, as there may be no need to invoke a novel form of life to explain these outcomes.

-

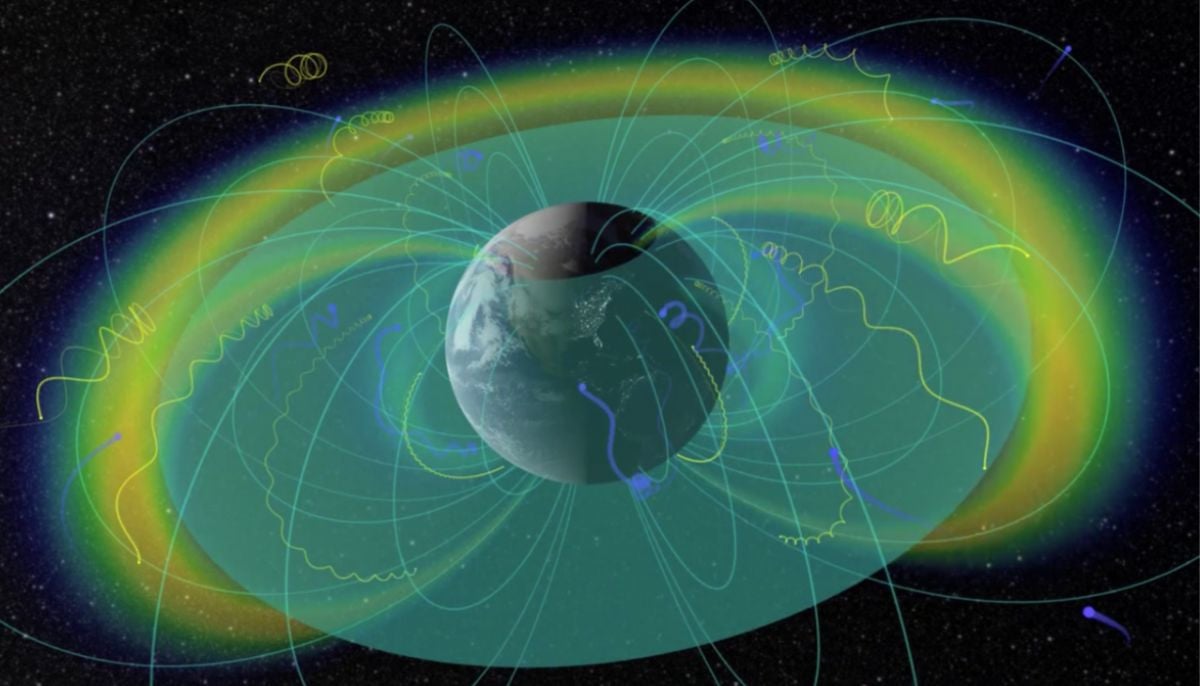

‘Smiling electrons’ discovered in Earth’s magnetosphere in rare space breakthrough

-

Archaeologists unearthed possible fragments of Hannibal’s war elephant in Spain

-

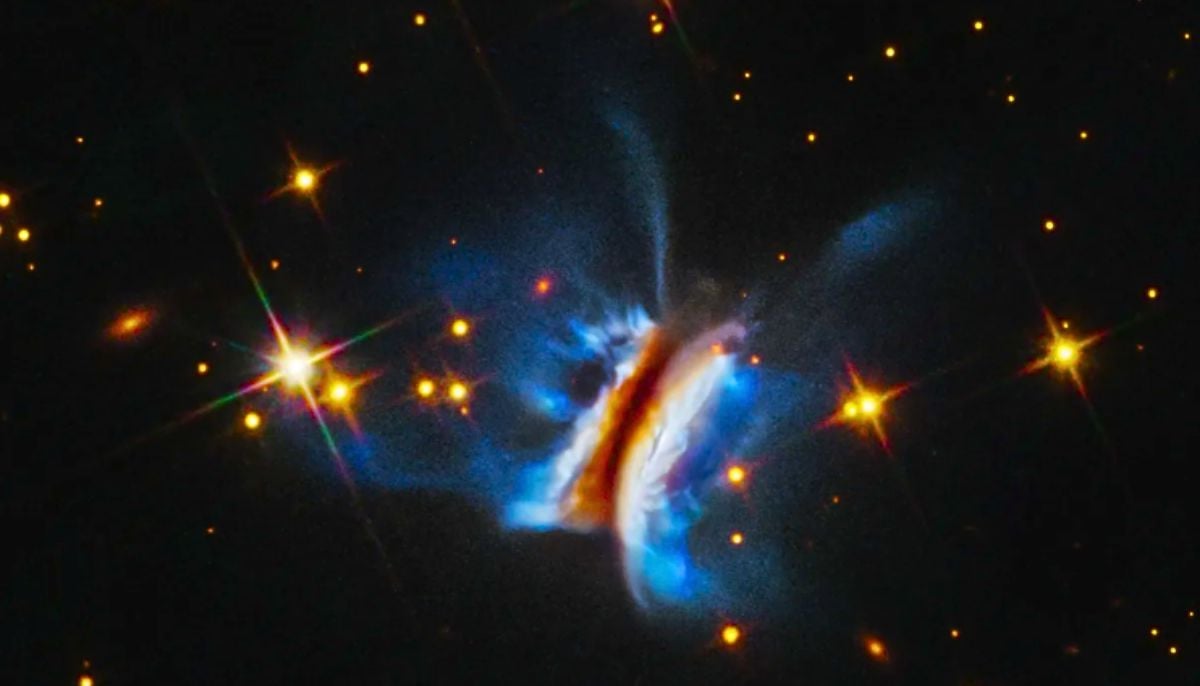

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope discovers ‘Dracula Disk', 40 times bigger than solar system

-

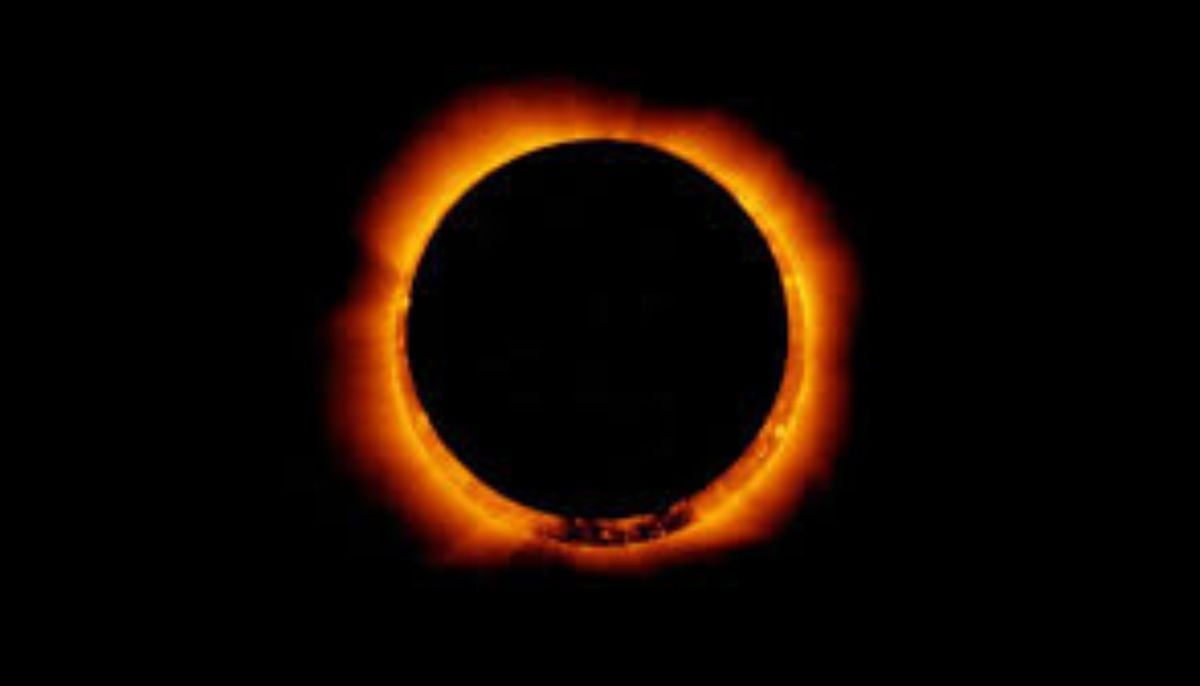

Annular solar eclipse 2026: Where and how to watch ‘ring of fire’

-

Scientists discover rare form of 'magnets' that might surprise you

-

Humans may have 33 senses, not 5: New study challenges long-held science

-

Northern Lights: Calm conditions persist amid low space weather activity

-

SpaceX pivots from Mars plans to prioritize 2027 Moon landing